– How and when did you become interested in photography?

I became fascinated with photography while still a child, when I procured a simple plastic camera for 50 cents and 30 Bazooka Joe bubble gum comics. On my first roll of B&W film, I photographed the grass at my feet, filling the frame with a homogeneous texture, which I continued to do at times for the next 60 years.

– Is there any artist/photographer who inspired your art?

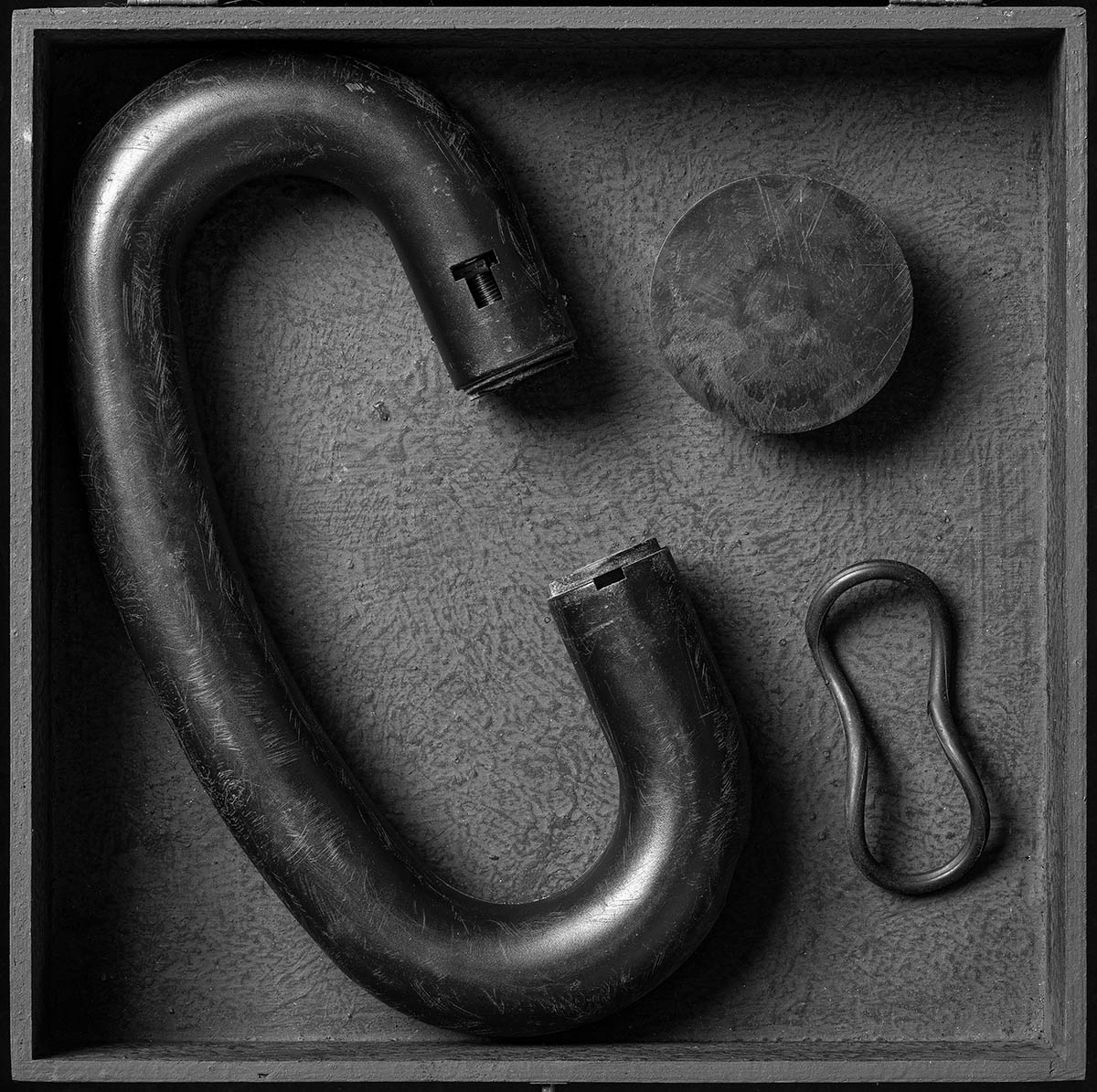

Many artists and photographers have inspired me: Memling and the Van Eyck brothers, William Harnett, Samuel Beckett, Joel-Peter Witkin, and Joseph Cornell, just to start. I relate powerfully to many things in art history.

– Why do you work in black and white rather than colour?

I prefer black and white to try to reduce my subjects to their essentials, and to take them even a little bit more out of context.

– How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph/series of photographs?

I put a great deal of time into preparing and executing a photograph. First of all, the subjects are generally things I found years ago and kept for eventual use in a photograph. I sort and store the objects, then take them out and ponder them from time to time. Eventually a composition takes shape in my mind, including the choice of a setting. Instinctively I combine things that have some sort of affinity with one another. When I have what I want – at the last phases, working on the set with the lighting I will use – I take a few trial exposures to confirm that all is right. If it is to be a multi-section image, I make a trial assembly in Photoshop to make sure the pieces will fit together properly.

Then I proceed to make a series of exposures of every section, starting from the part of the subject nearest to the camera, then focusing slightly further back, and further, until I get to the base, the furthest pane of focus. These exposures could be fifteen or more – an excess, to be sure, but given the inaccuracies of focusing, it assures me of having the entire depth adequately covered. This is especially a challenge when working very close to the subject, as anyone will know who has done some “macro” photography. (Note to those who think, “well, why don’t you just use f/22?” Because the smaller apertures reduce definition noticeably, even though they offer more depth of focus. I typically use f/11, which is an optimal aperture for definition.)

Those many exposures are combined into a stack, their sizes being adjusted so they will all coincide perfectly. I compare them visually and can usually eliminate a few as redundant. I work with the remainder, perfecting the masks in every layer that show the sharpest parts and hide the less sharp. This can take weeks of labor, but gives complete depth of focus. (I developed this technique as a result of my frustration with the digital camera as compared to the view camera, which I used for years before switching to digital, making still-life photographs in a very similar style.) The files are sometimes so big that, to work with them and to be able to save the modifications, I have to divide the layers in two or even three groups, each of which can weigh no more than 4GB. In these cases I combine the groups only at the end to make a definitive, one-layer file.

All this technical stuff means nothing, however, except insofar as it reinforces the aesthetic expression I’m looking for. I feel that, in an age when things are as superficial as they are instantaneous, to work in this labor-intensive way implies another level of commitment to the art. I have thought that perhaps I should have lived in the Middle Ages and lived as a monk who passes all his time making illuminated manuscripts.

One thing I don’t spend much time on is the lighting, which I change only a little from picture to picture. My needs are terribly simple: a soft light that approximates the window light of many old still-life paintings, or the north light of the photo studios of the 1800s. I suppose this taste is of a piece with my general antipathy for modernity.

– Where is your photography going? What projects would you like to accomplish?

I don’t anticipate any particular big developments. I already have a style in which I’ve been working satisfactorily for a long time, and in my studio I have many storage shelves full of material to use in creating new works in still life. I have more picture ideas than I can ever hope to carry out.

Website: www.allenschill.com

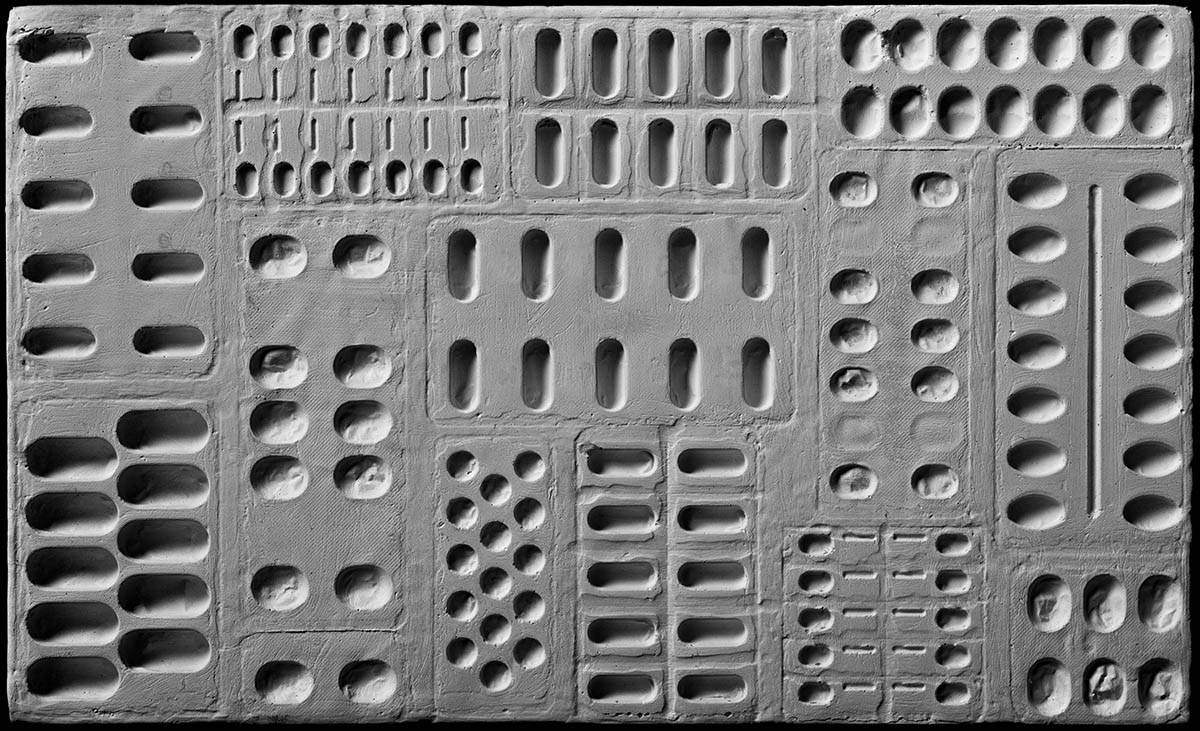

A still life of a number of multicolored party balloons, allowed to deflate slowly over the course of several years, and arranged in a shallow box.

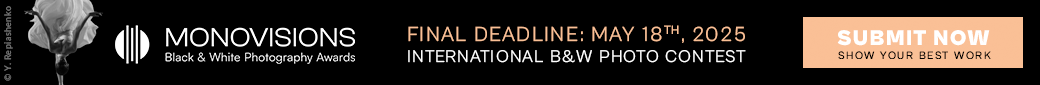

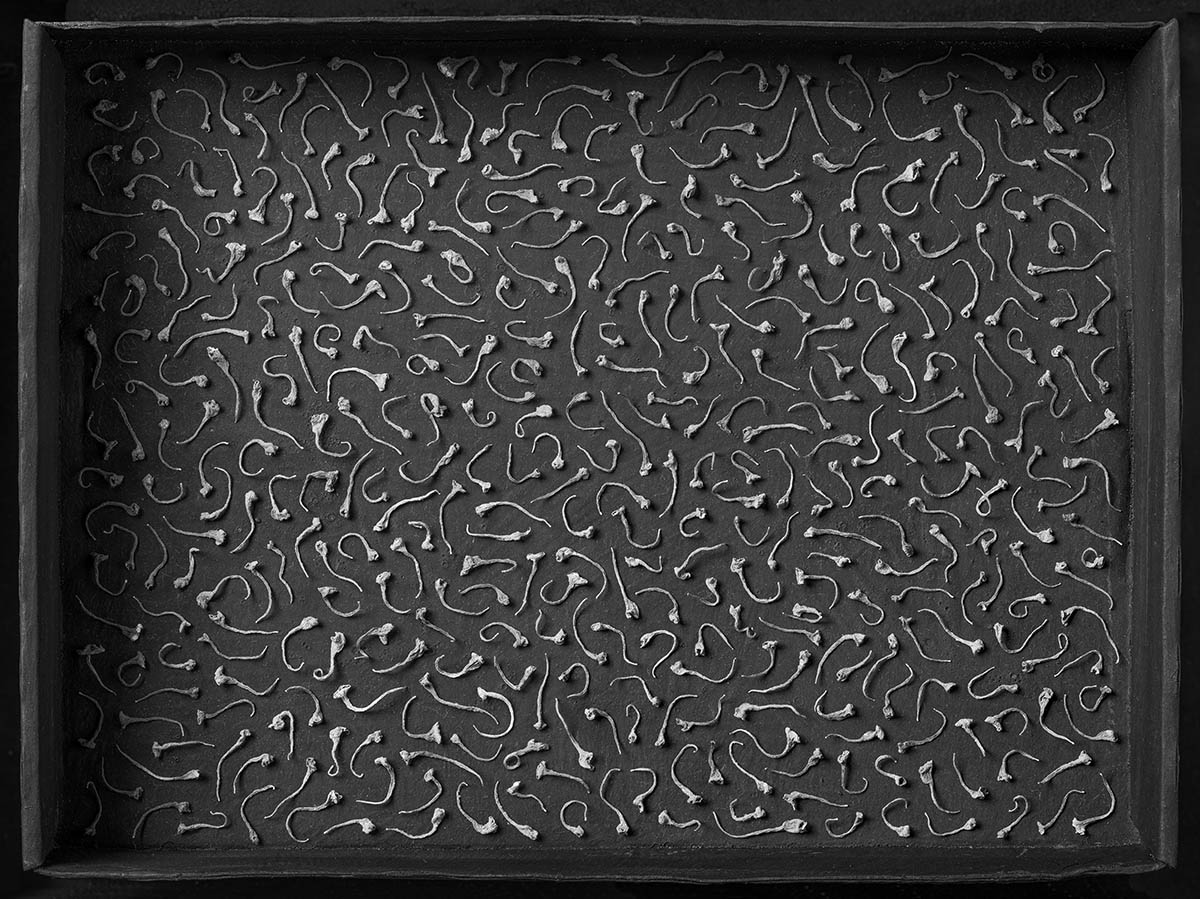

A still life of a number of toy balloons, allowed to deflate slowly, arranged in a box, and painted black.

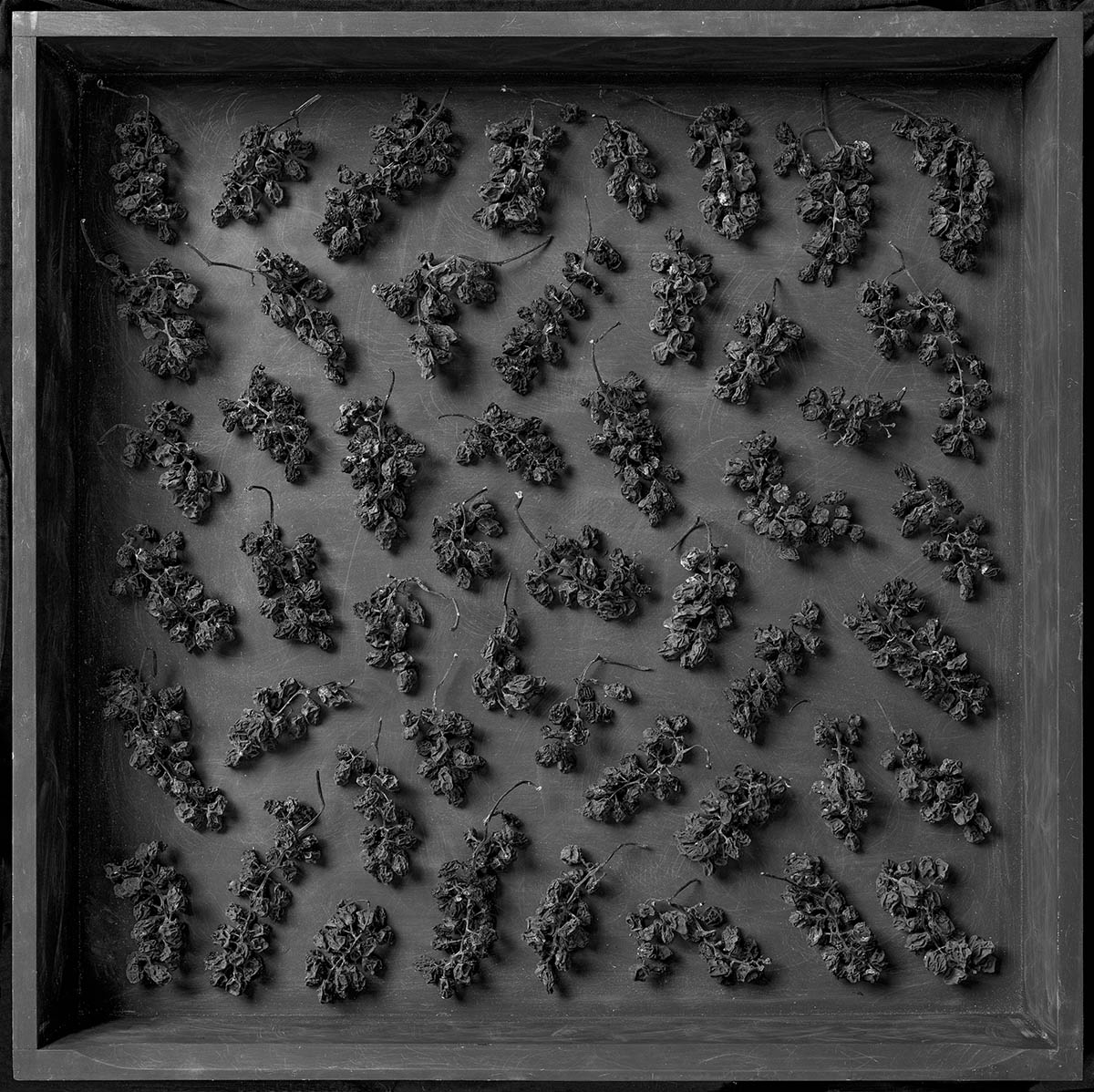

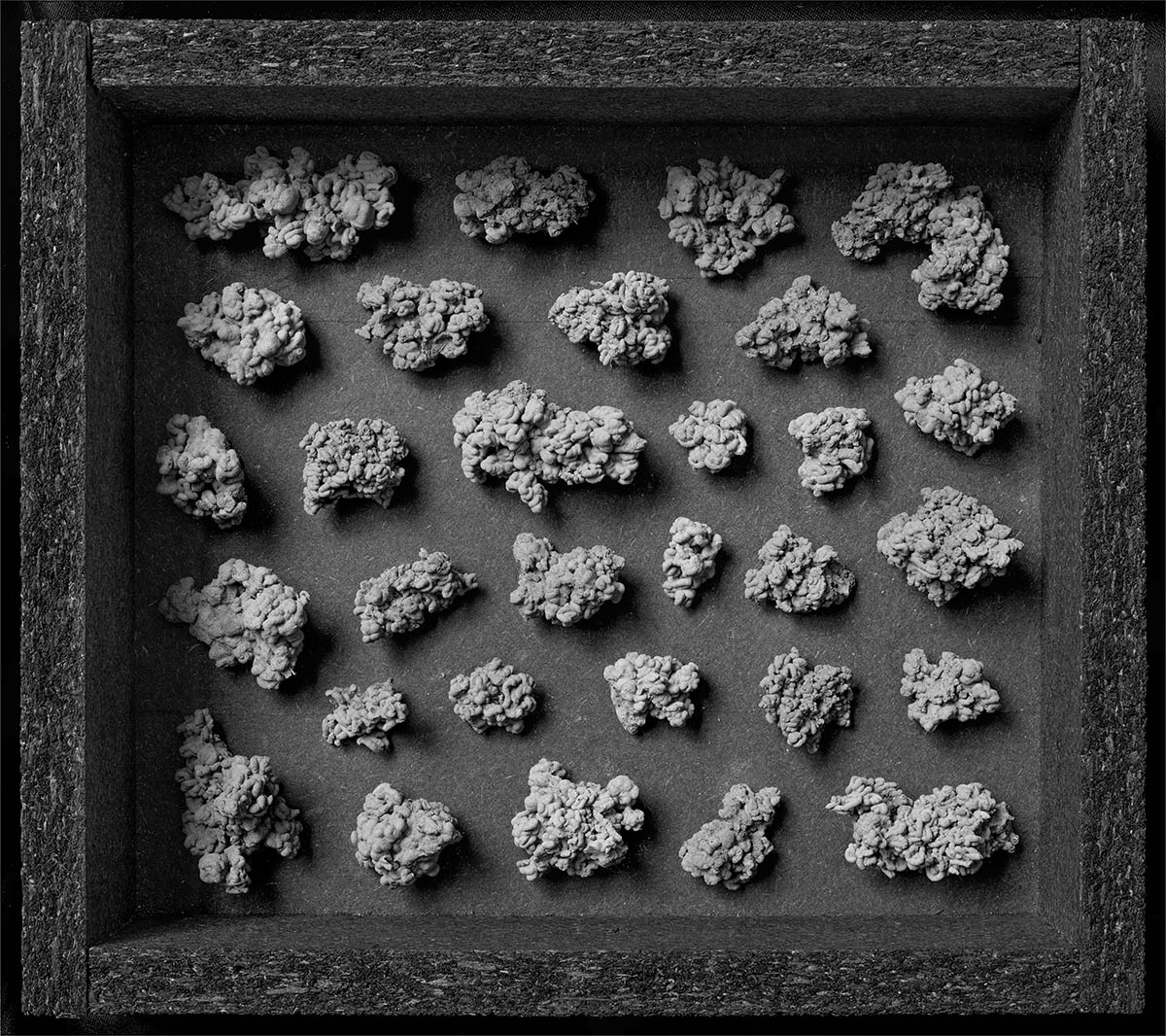

An arrangement of worm casts – the little piles of of mud excreted above the surface of the ground by earthworms.

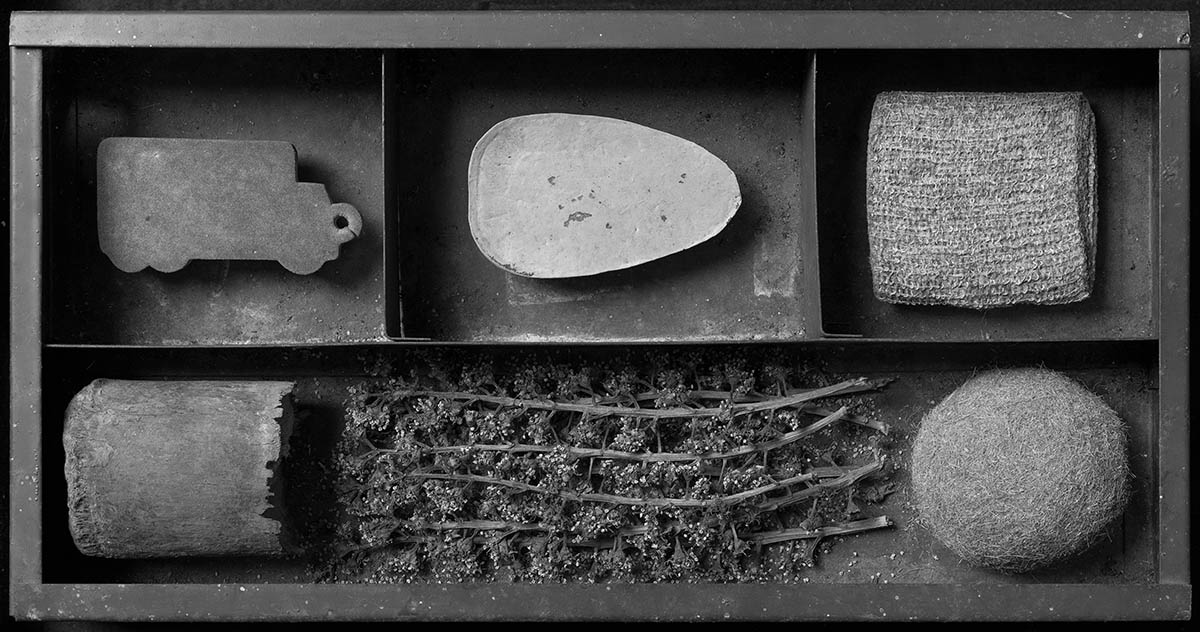

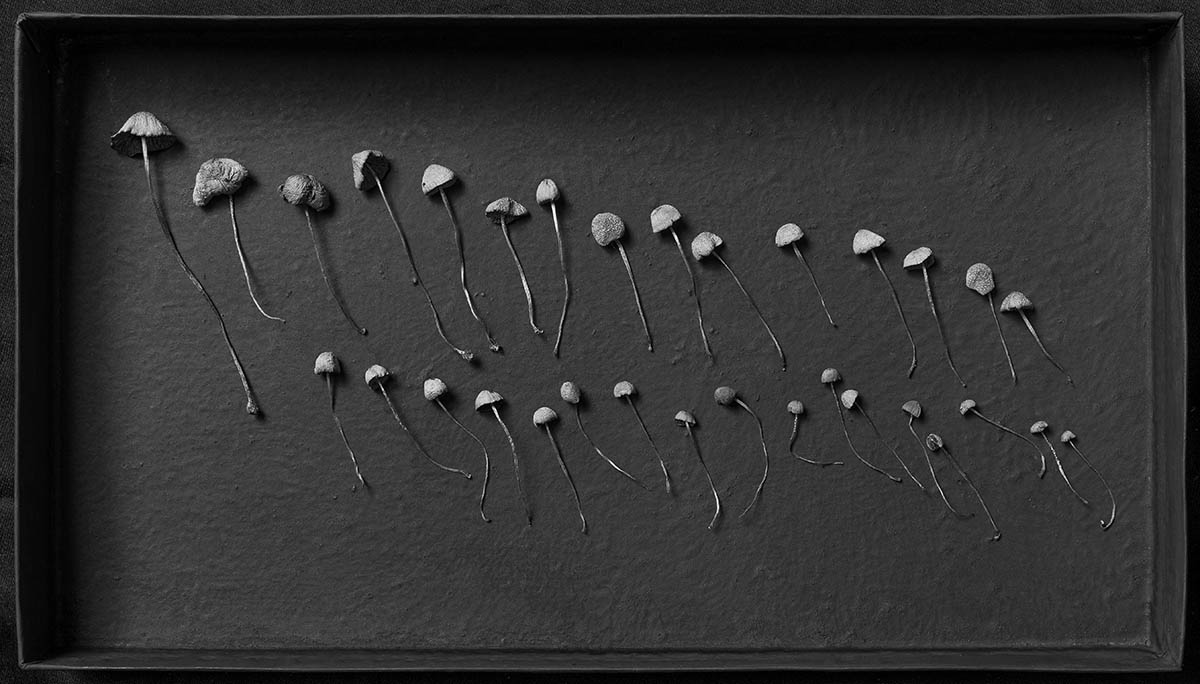

An arrangement of small, dried, wild mushrooms allowed to dry, and aranged in a shallow black tray to evoke a school of jellyfish (“meduse” is Italian for jellyfish, in the plural).