Herbert George Ponting (1870 – 1935) was a Brisitsh photographer. He is best known as the expedition photographer and cinematographer for Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition to the Ross Sea and South Pole (1910–1913). In this role, he captured some of the most enduring images of the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration.

After winning several photographic contests he was hired by a stereopticon company to produce views for their machines. He travelled widely in the Far East, South-East Asia and Europe and was a pioneer in the use of the camera as a medium of art rather than a mere recorder of events and persons. From 1904-05 he covered the Russo-Japanese War for Harpers Weekly. In 1910 he published his first illustrated book In Lotus Land Japan this resulted in Ponting being recognised internationally as a popular photographer and travel writer. It was images from his travels which he used to entertain expedition members on their voyage to Antarctica.

He was selected for the British Antarctic Expedition, 1910 – 1913 (leader Robert Falcon Scott), as the expeditions photographer or camera artist as he preferred to be known. He hoped that his images would contribute to geographical knowledge and in the settling of the expeditions finances on their return. The technical difficulties of photography in the Antarctic were formidable but Ponting overcame these problems by his technical mastery. He built himself a small darkroom in one of the huts at Cape Evans. Here he spent 14 months, producing over 1000 photographs. He photographed the behaviour of seals and other mammals and birds, behaviour that had previously been a matter of speculation, producing many valuable scientific records. These photographs also act as a visual diary of expedition life. Ponting strived to get the perfect photograph and often put himself or expedition members in risky situations, for example constructing hoists to hold himself and his equipment over the edge of the ship in order to get the exact shot he desired. Many of the expedition members were asked to pose for photographs, this became know as ‘ponting’ i.e. posing for photographs in uncomfortable positions in cold weather whilst Ponting tried to get his perfect shot.

During the expedition Ponting also captured moving pictures, having been on a crash course just before the expedition and acquiring a specially adapted Newman-Sinclair camera. His film of the expedition Ninety Degrees South (1933) remains a classic of polar photography, however, at the time it cost Ponting a lot of money and failed to be a commercial success.

He left the Antarctic in February 1912 as it was felt he was too old to endure another Antarctic winter.

One of Ponting’s pictures shows sled dogs housed on the deck of the wooden whaler Terra Nova during her sail to Antarctica in 1910. Among the ship’s cargo were 3 motor sledges, 162 mutton carcasses, 19 ponies, 33 dogs, and more than 450 tons of coal—not to mention 65 people, from sailors to scientists.

Expedition cook Thomas Clissold and surgeon Edward Atkinson (right) haul up a seal-baited fish trap during Antarctica’s winter darkness. The team’s nearly three years of scientific experiments—particularly in meteorology and geology—laid the groundwork for what is known about the continent today, Jones said. In addition to their drive to reach the Pole, he said, Scott and his men “were also driven by a passion to discover more about the world.”

Men eat lunch in a tent on January 7, 1911—not long after the Terra Nova landed at Cape Evans in Antarctica. Scott chose to build the expedition hut at Cape Evans because the location provided easy access to the Ross Ice Shelf—a France-size piece of ice that would make up the first section of the South Pole trek.

Lieutenant Edward Evans and biologist Edward Nelson chisel an ice cave for food storage on January 12, 1911. Though making it was “slow and arduous work,” Scott wrote in his journal, he predicted that, once complete, the larder “will be admirable in every way.”

Expedition members give whiskey to a pony that swam ashore after being stuck on an ice floe in McMurdo Sound on February 8, 1911. While laying supply depots in preparation for the South Pole trek, the men encountered many challenges, including unreliable ice and blizzards.

Lieutenant Henry Rennick uses an instrument called an artificial horizon to take readings of Earth’s natural horizon on February 9, 1911. The Terra Nova scientific team was the largest to date in Antarctica, part of Scott’s goal to “take every advantage … to study natural phenomena,” as he wrote to the British Royal Geographical Society before his journey.

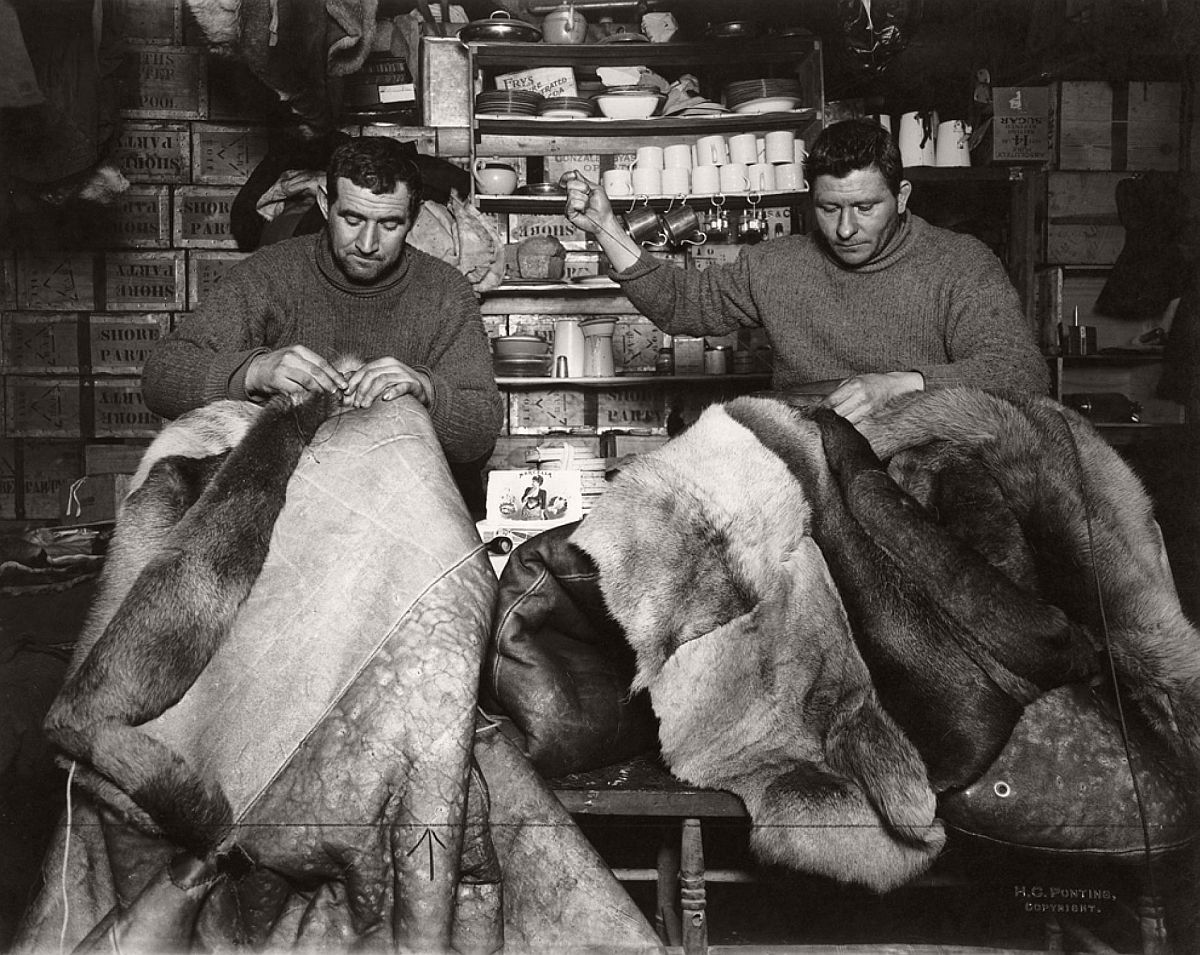

Expedition members repair reindeer-fur sleeping bags inside the Terra Nova hut on May 16, 1911. For the South Pole journey, the men wore warm, reindeer-fur boots called finneskos, oversize reindeer-fur mitts, and goggles to prevent snow-blindness.

Members of the western geological party haul a sledge across sea ice in 1911. The team, led by geologist T. Griffith Taylor, was the first to explore Antarctica’s Western Mountains—in Scott’s words, a “vision of mountain scenery that can have few rivals.”

Lieutenant Edward Evans observes an occultation of Jupiter—which occurs when Jupiter passes between Earth and a star—on June 8, 1911. The Terra Nova explorers also witnessed several meteorological events, auroras possibly being the most impressive. “Tonight we had a glorious auroral display—quite the most brilliant I have seen,” Scott wrote in May 1911. “At one time the sky from N.N.W. to S.S.E., as high as the zenith, was massed with arches, band, and curtains, always in rapid movement.”

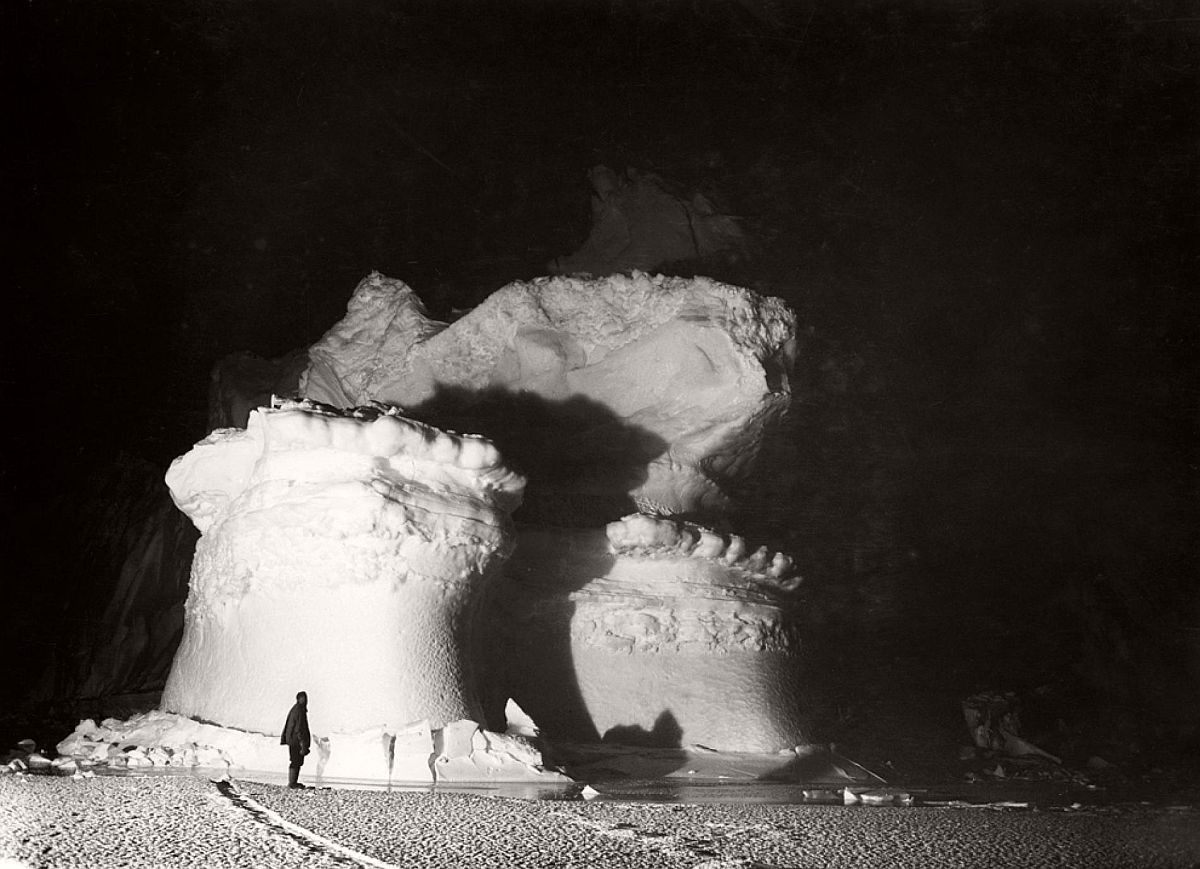

“A great bastion of ice”—Ponting’s description for this feature photographed in September 1911—is among many unusual ice formations observed during the expedition. For instance, sledging parties often encountered sastrugi, wind-sculpted snow that can resemble the surface of a stormy sea. The men learned to “read” the sastrugi to determine the direction of the wind and then pitch their tents accordingly.

Biologist Edward Nelson tends to a scientific experiment in an ice hole on December 24, 1911. Terra Nova biologists were fascinated by the bevy of unusual creatures around them, from leopard seals—which they called sea leopards—to killer whales to Adélie penguins.

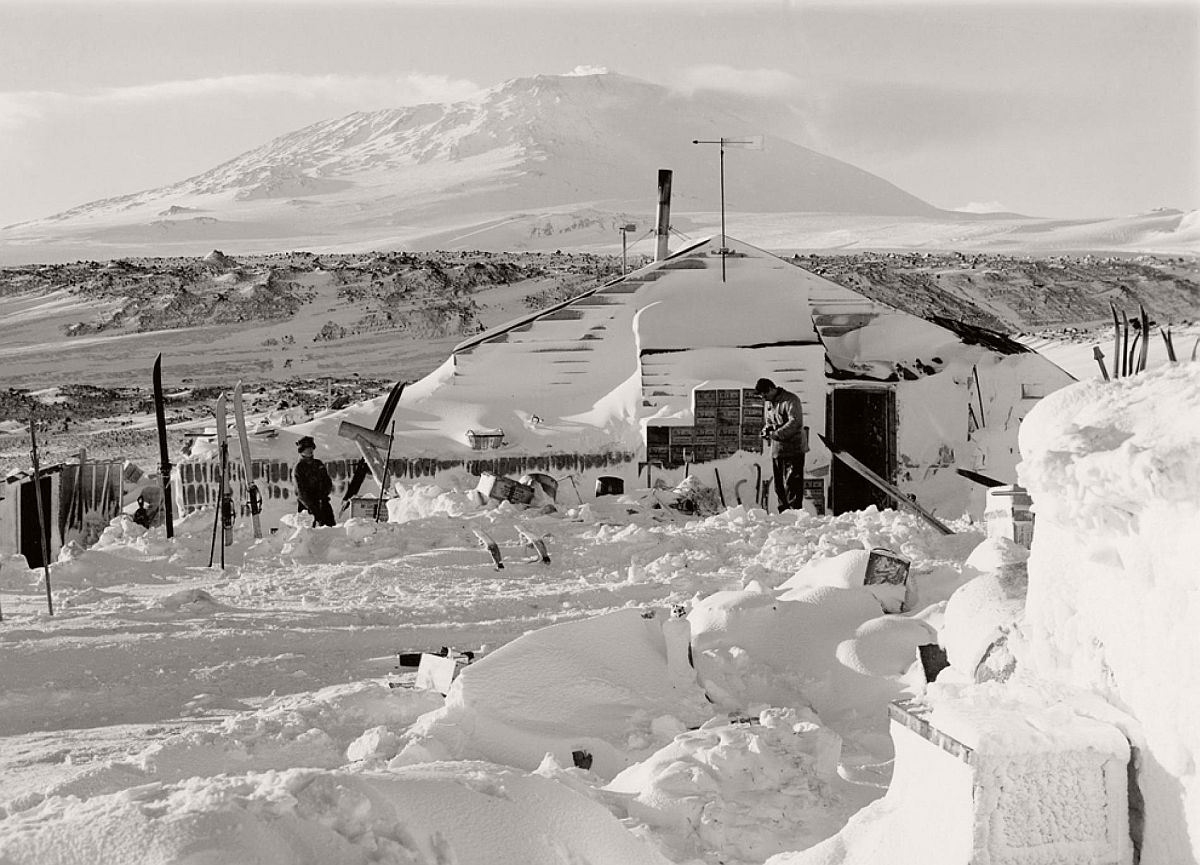

Men emerge from the Terra Nova hut on September 17, 1911—a relatively “warm” spring day of -15 degrees Fahrenheit (-26 degrees Celsius). The 12,447-foot-tall (3,794-meter-tall) Mount Erebus, Earth’s southernmost active volcano, looms in the distance.

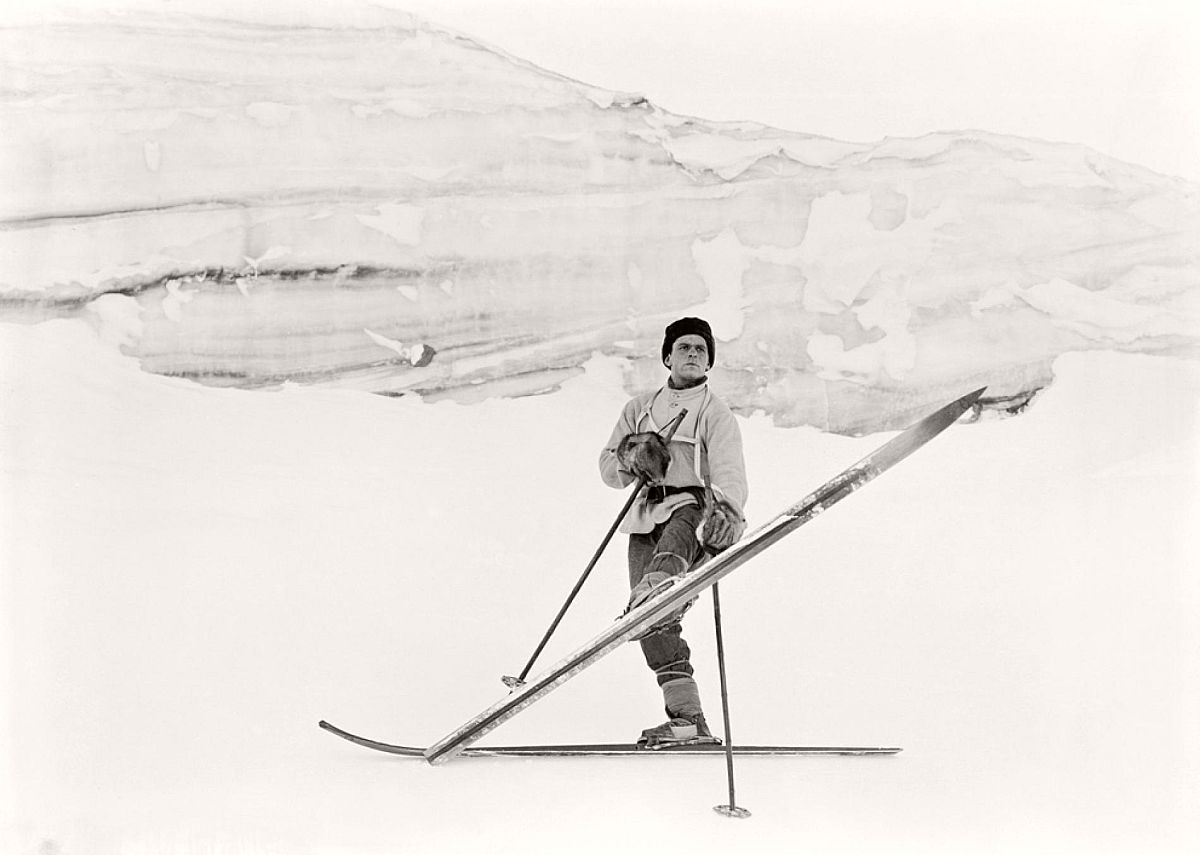

Norwegian ski expert Tryggve Gran executes a turn in October 1911. Gran, who was a sub-lieutenant on the expedition, also gave ski lessons to the South Pole trekkers—most of whom had little experience on skis.

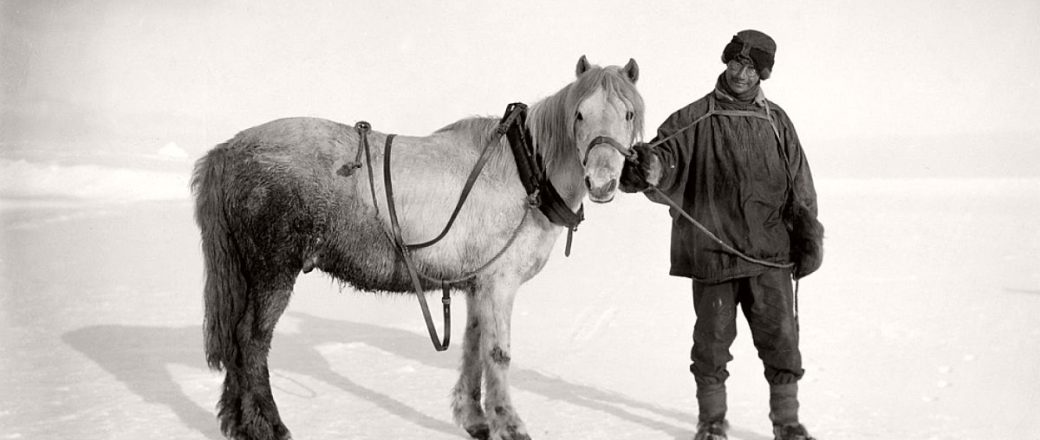

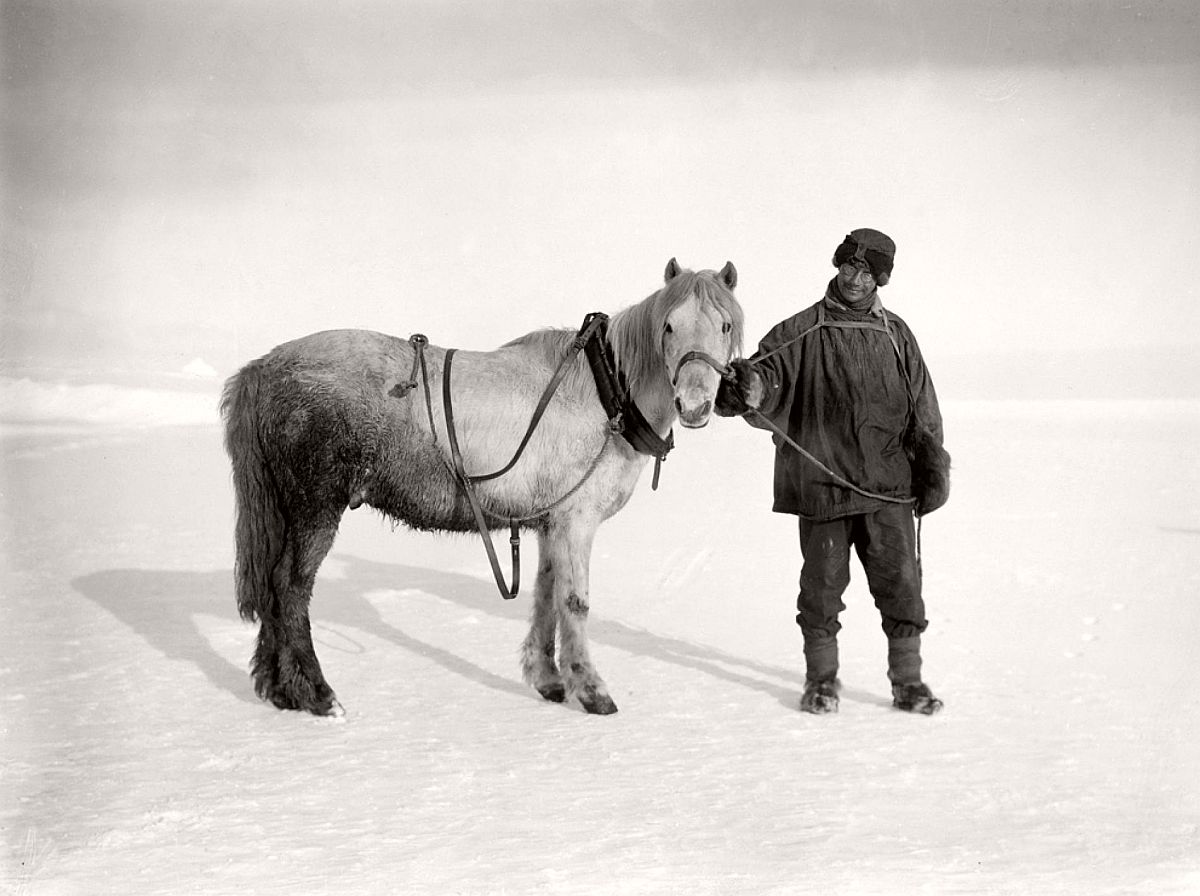

Assistant zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard is seen with his pony, Michael, on October 16, 1911, before the two started on the first leg of the South Pole journey. The pony “was as attractive a little beast as we had,” Cherry-Garrard wrote in his journal, although he “developed mischievous habits and became a rope-eater and gnawer of other ponies’ fringes, as we called the coloured tassels we hung over their eyes to ward off snow-blindness.” Michael and the other nine ponies died en route to stock up supply depots for Scott and his men on their return journey from the Pole.