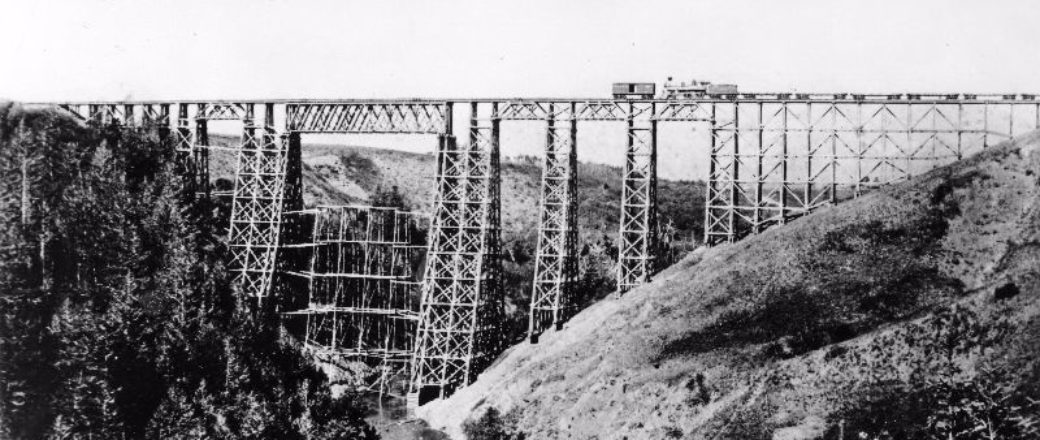

In the 1830s, the railroad boom started a new era in the building of railroad bridges pushing engineers to build towering wooden bridges that have become synonymous with the era.

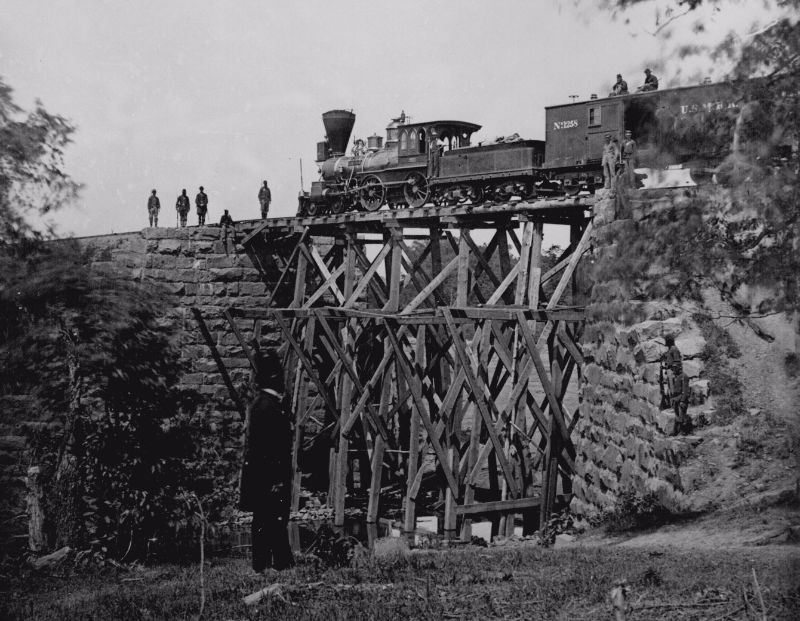

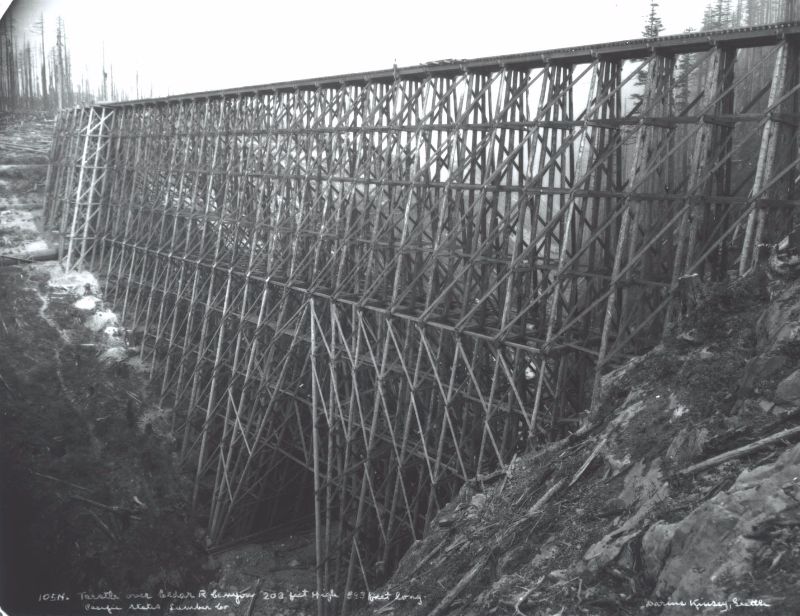

Timber trestles were one of the few railroad bridge forms that did not develop in Europe. The reason was that in the United States and Canada cheap lumber was widespread and readily available in nearby forests. The Pacific Northwest of the U.S. and the province of British Columbia, Canada became the central region for hundreds of logging railroads whose bridges were almost all made of timber Howe trusses and trestles.

Timber trestles generally come in two forms. The first and most common is the pile trestle which consists of bents spaced 12 to 16 feet apart. Each bent consists of 3 to 5 round timber poles that are pounded straight into the ground by a pile driver. The centre post is upright, the two inner posts are angles at about 5 degrees and the outside posts are usually battered, angling outward for stability at about ten degrees. During construction, the top of the uneven posts are cut to the proper level for a cap which in turn supports the stringers and planks that hold the rail. Taller pile trestles contain diagonal “X” bracing across one or both sides of the bent and also between bents.

For higher timber trestles, the framed bent is used. Unlike pile bents, frame bents usually use square timbers and rest on mud sills or sub sills that act as a foundation. Frame bents are built in a series of “stories” that are usually between 10 and 50 feet high. For extremely high trestles, each section of the bent is built flat on the ground as a single or double story and then lifted and placed onto the ever lengthening trestle.

None of the dozen or so highest timber bridges of all time exist anymore. Nearly half of these 200 foot high monsters were built for logging railroads in the U.S. state of Washington and on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Canada. For the lumber industry, rail lines were usually little more than a web of dead end tracks blanketed across the contour lines of a forested mountainside. Once the terrain was logged out, the tracks were abandoned. Since lumber was easy to find and abundant, it could quickly be cut on-site into tall piles or bents. With nothing built to last, construction standards were often low. Expensive bridges, especially those made of steel, were avoided by the loggers.

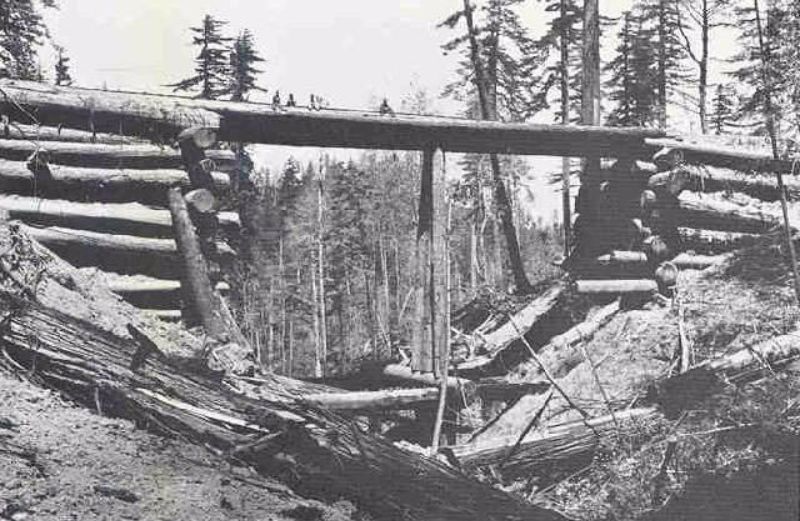

A home-made log bridge. The men sitting atop it give an idea of its height, and the diameter of the redwood logs used for construction.

via Atchuup!