The forces of nature are natural phenomena always present in a landscape, beyond human control. Ole Brodersen‘s work is dedicated to unveiling this presence by exploring encounters between manmade objects and untouched nature.

Brodersen grew up in Lyngør, a car-free archipelago in Norway with 100 inhabitants. His family has been living here for 12 generations. Ole‘s father is a sail maker and his grandfather was a sailor. He rowed to school and sailed from the age of 6.

The mainland appears to him as static, firm and controllable. The ocean, on the other hand, is like an unconquered frontier of nature. Living on this threshold, you grow up to be constantly aware of the changes in the air and sea. High tide? Check the moorings. Heavy snowfall? Shovel snow off the boats.

In 2008 Ole circumnavigated the Atlantic Ocean in a 120-year-old pilot cutter. It was mostly about the adventure, and to some extent to put him to the test. But Ole has now followed the wake of his forefathers. The experience did not necessarily mark the beginning of something, but rather a return to what he was all along. A homecoming of sorts.

Preparing for his recordings, Ole collects various materials such as: Styrofoam, pieces of sailcloth and rope, out of which he makes objects that will populate the landscape. Most of the material is found while rummaging through his grandfather‘s shed or his father‘s sail loft. Out of these Ole fashions markers; i.e. floats, flags, kites and different light sources.

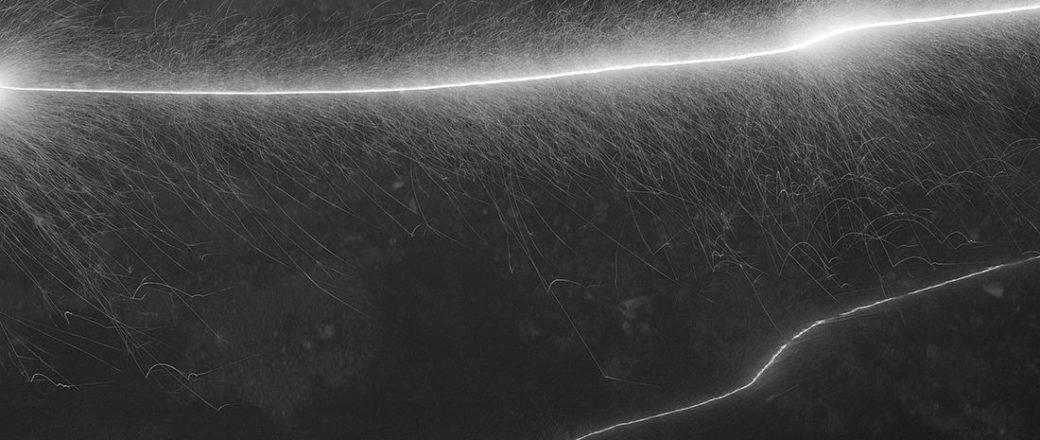

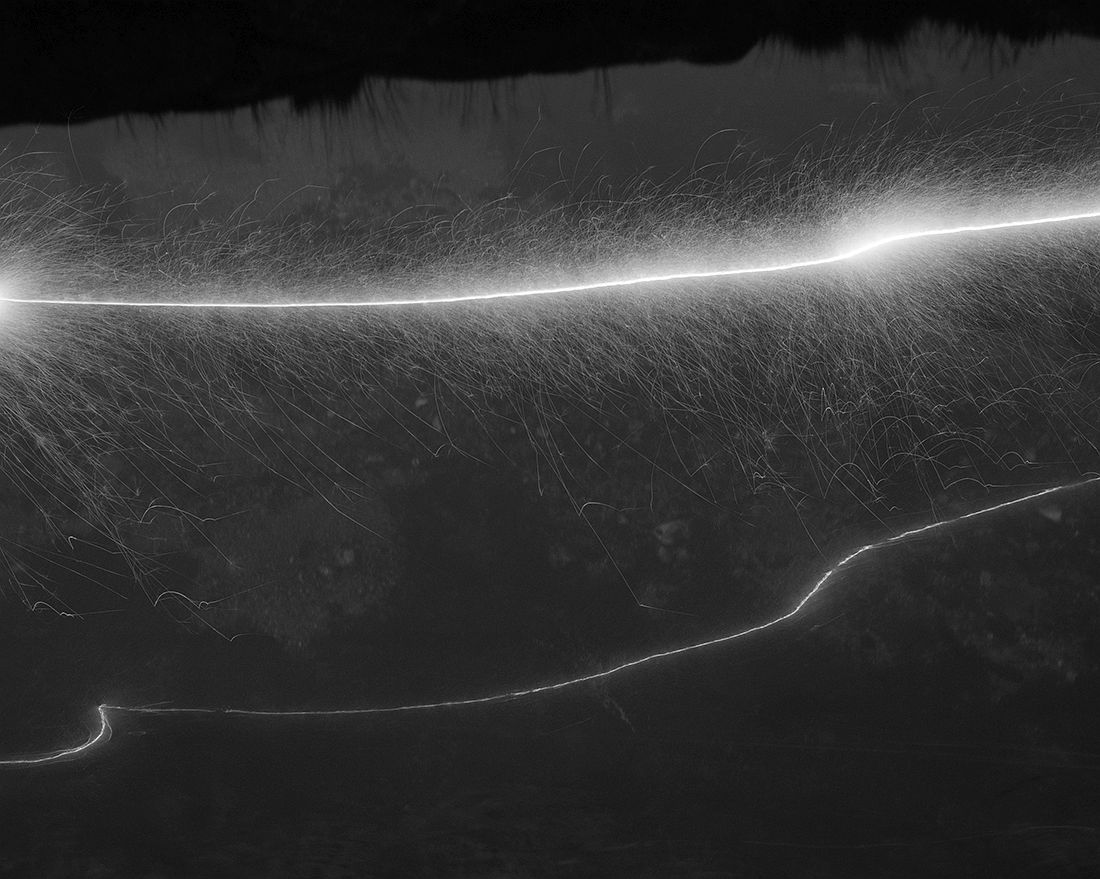

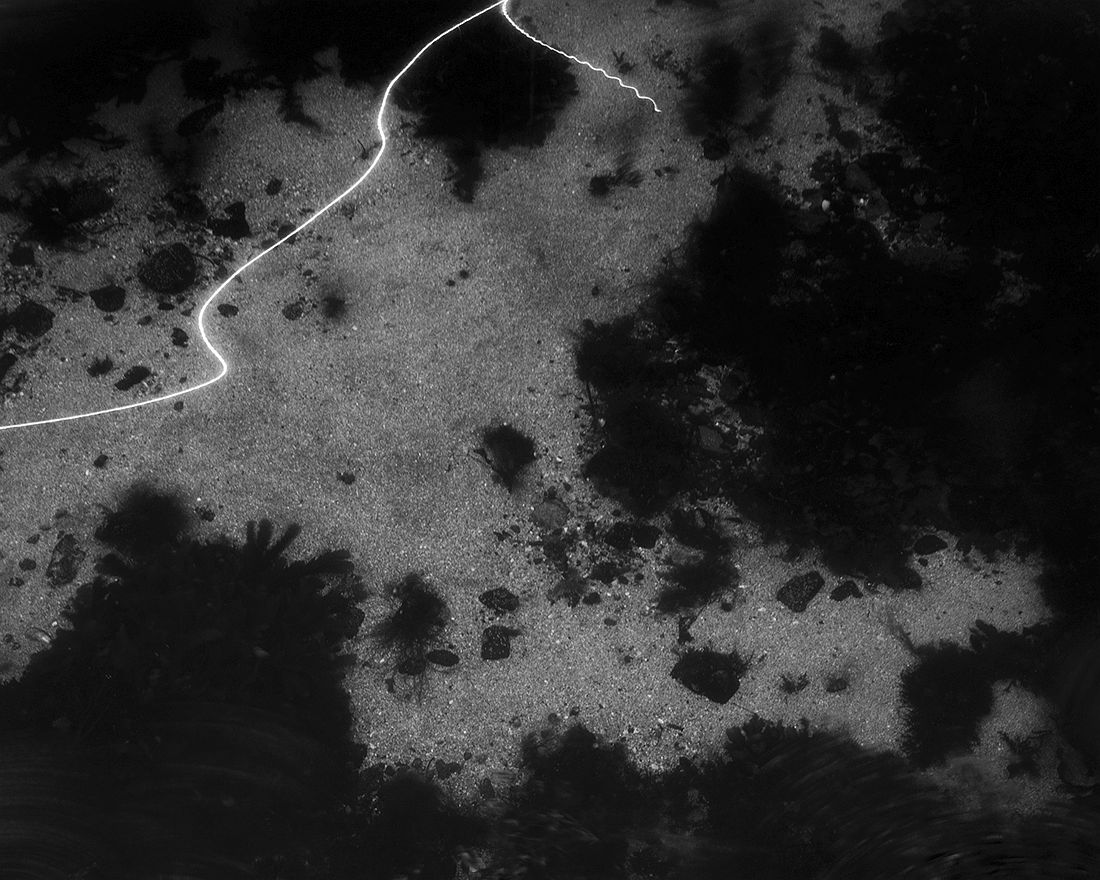

Waves, tide, wind and currents decide where the recordings will take place. At a suitable location, Ole deploys his markers, starts the chosen exposure and waits while it develops in front of him.

The photographs reveal movement that is unnoticed, rather than undetectable. A useful analogy is false-color; a technique used in deep space imaging to visualize different unobservable phenomena. Images taken by telescopes are often in wavelengths invisible to the human eye, and needs to be mapped into our perceptual range. We know that these astronomical phenomena aren‘t presented the way they actually look, but otherwise they would remain undetected by us.

The titles are the list of ingredients used to create the markers. The titles are in the photograph, rather than underneath them. Their function is to demystify, rather than to comment. It is not his wish for the observer to spend time solving riddles. In addition, he wants to underline the importance of the coincidences that occur during the process, how unpredicted events and using what he has at hand leaves a mark on the result.

The final image is a result of the weather conditions that particular day, but also of the materials being used. The entire procedure enables nature to yield a figure of movement. Invisible force is captured into a visible sign.

– How and when did you become interested in photography?

I believe the turning point came while circumnavigating the Atlantic Ocean. I felt the need to create something tangible as opposed to the fleeting experiences we went through. Up until then I was a digital snapshooter, and switching to film made a big difference for me. First with 35mm, but then it all got even more serious when I started with large format and 4×5 negatives.

– Is there any artist/photographer who inspired your art?

My series “Trespassing” is influenced by the long exposure master Gjon Mili and the chronophotographer Eadweard Muybridge.

– Why do you work in black and white rather than colour?

I work with both actually. I switch back and forth, and sometimes even doing the same composition with both. Which makes it impossible to choose, so I have to stop doing that. They both have their advantages, and it is hard to say when I prefer what. When the islands here are covered in snow for example, and the light is flat, it is almost like everything is black and white already. In these situations, it is tempting to introduce some color. On the other hand, the summer light can sometimes be so saturated that I need to turn to black and white to be able to focus.

– How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph/series of photographs?

My photographs are site specific. I work in the area surrounding Lyngør, an archipelago of islands and rock formations; a very characteristic feature for Fennoscandia (and Scotland), that was shaped by glaciers that used to cover these lands.

Preparing for my recordings, I collect various materials such as: Styrofoam, pieces of sailcloth and rope, out of which I make objects (of different complexity) that will populate the landscape. Most of the material is found while rummaging through my grandfather‘s shed or my father‘s sail loft. Out of these I fashion markers; i.e. floats, flags and kites. Sometimes attaching additional sparklers, LED-lights or other light sources, which help trace their trajectory through the landscape.

I use a large format camera and often long exposures that allow me to capture the movements of my markers. I always bring multiple markers with me. Waves, tide, wind and currents decide where the recordings will take place. At a suitable location, before composing, I always test-run a few of the markers, to get a feel for the pathway of the forces. Afterwards, I have no influence on the final exposure. I deploy my markers, start the chosen exposure and wait while it develops in front of me. The nature takes control of the markers.

– Where is your photography going? What projects would you like to accomplish?

I see it continue like now, endlessly hopefully, but I have always been doing related side-projects, which I think will take up more of my time in the future. This will probably shape Trespassing’s evolvement as well. Right now, I am doing some experiments with triple exposing the horizon from my boat.

Website: olebrodersen.com