Augustus Washington (1820 – 1875) was an African-American photographer and daguerreotypist, who later in his career emigrated to Liberia.

Washington grew up in the Americas of the 1820s, a time when African Americans were denied even the most basic rights. Against all convention, all he wanted to do was study. He struggled to get admission into various educational institutions across America, when he finally got an entry into Dartmouth College, New Hampshire, in 1843. It was here that he learned how to make daguerreotypes and work in a darkroom during his freshman year.

Unfortunately, he was under severe debt, so he had to give up college and move to Hartford, Connecticut. Washington was an enterprising man, so he set up his own photo studio in 1846 for earning an income.

There were not a lot of photo studios in Hartford at the time, which worked extremely well towards Washington’s advantage. He took out full-page advertisements in abolitionist newspapers, which offered daguerreotype portraits between 50 cents to 10 dollars, a princely sum back then, but still inexpensive for a process and art that was just becoming popular. “Why should not the Daguerreotype be within the reach of everybody?” the ad asked, “While others are advocating every man a house, free soil and free speech, it remains for Washington to advocate and furnish free Daguerreotypes, for the next 60 days.”

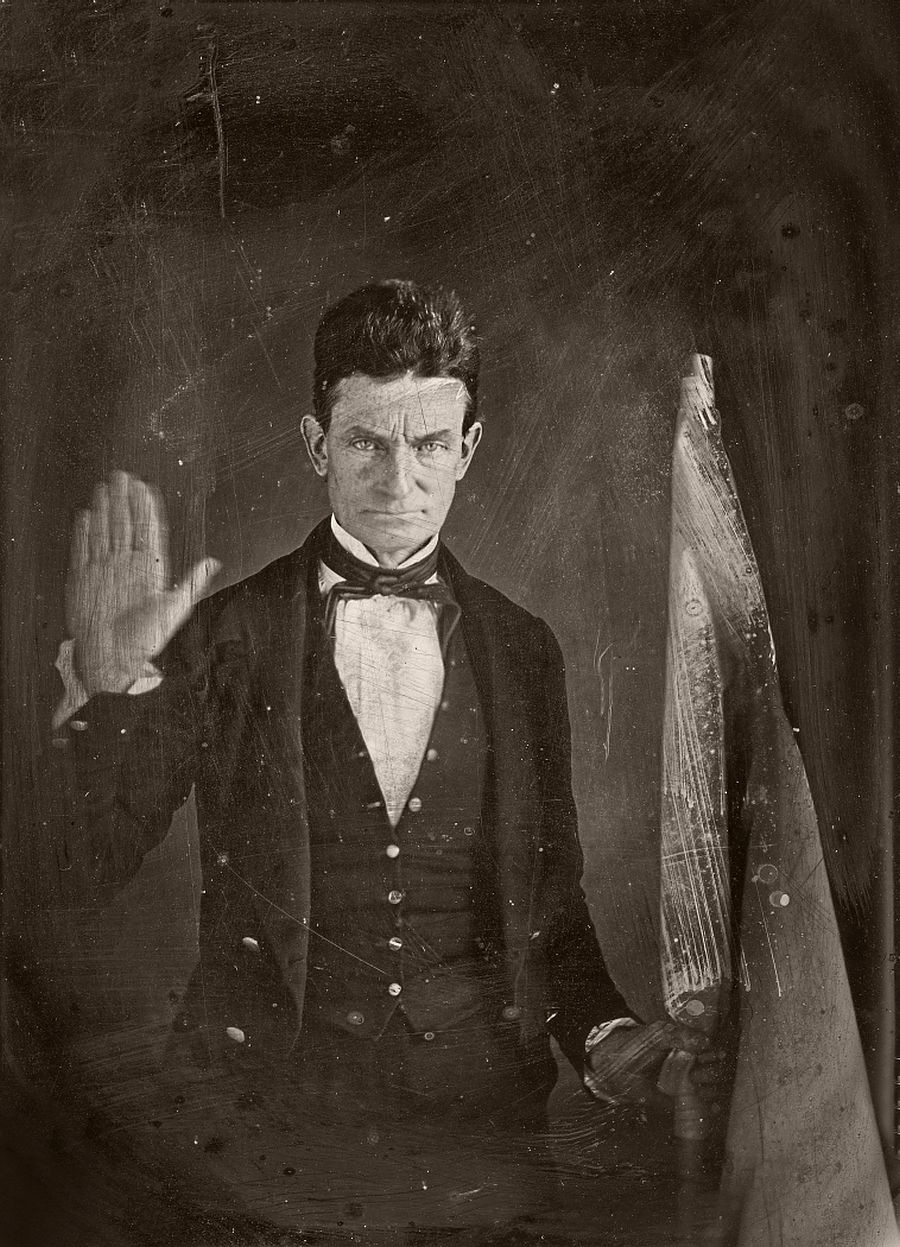

Soon, Hartford residents began paying a visit to his studio to get their portrait made. Some of them included Lydia H Sigourney, one of 19th century’s most prolific poets, and of the first American women published poets, political leader Eliphalet Adams Bulkeley and radical abolitionist John Brown.

Washington’s daguerreotypes are nuanced and showcase his skill as a portraitist. Because of his education, he understood light and composition. Many of his photographs have his subjects captured from the side, a style that was unseen at the time. He did not make images for the sake of creating them… one can see the though that has gone behind each photograph.

Even though business was booming, Washington would not turn a blind eye towards the rampant slavery and the atrocities that were faced by his fellow African Americans in the country. In 1853, he decided to move to Liberia, Africa.

Before he left, he published a small announcement in the Hartford Daily Courant that said that he was retiring from the business, “not from any want of further success or patronage, but for the purpose of foreign travel, and to mingle in other scenes of activity and usefulness.” He soon made his journey to Liberia, to start life all over again.

In a documented letter to The Tribune, Washington wrote about ‘colonising’ Africa, as a man of colour. He said, “I have been unable to get rid of a conviction, long since entertained and often expressed, that if the colored people of this country ever find a home on earth for the development of their manhood and intellect, it will first be in Liberia or some other parts of Africa. We must mark out an independent course and become the architects of our own fortunes.” In Liberia, he experienced the kind of freedom he could not, back in USA.

Washington built another successful studio in Liberia. He continued to correspond with Lydia H Sigourney, and even sent her 50kgs of sugar produced by his own crop of sugarcane. He eventually gave up photography and became a farmer, thereby fulfilling his wish to pursue other avenues to gain the most out of life.

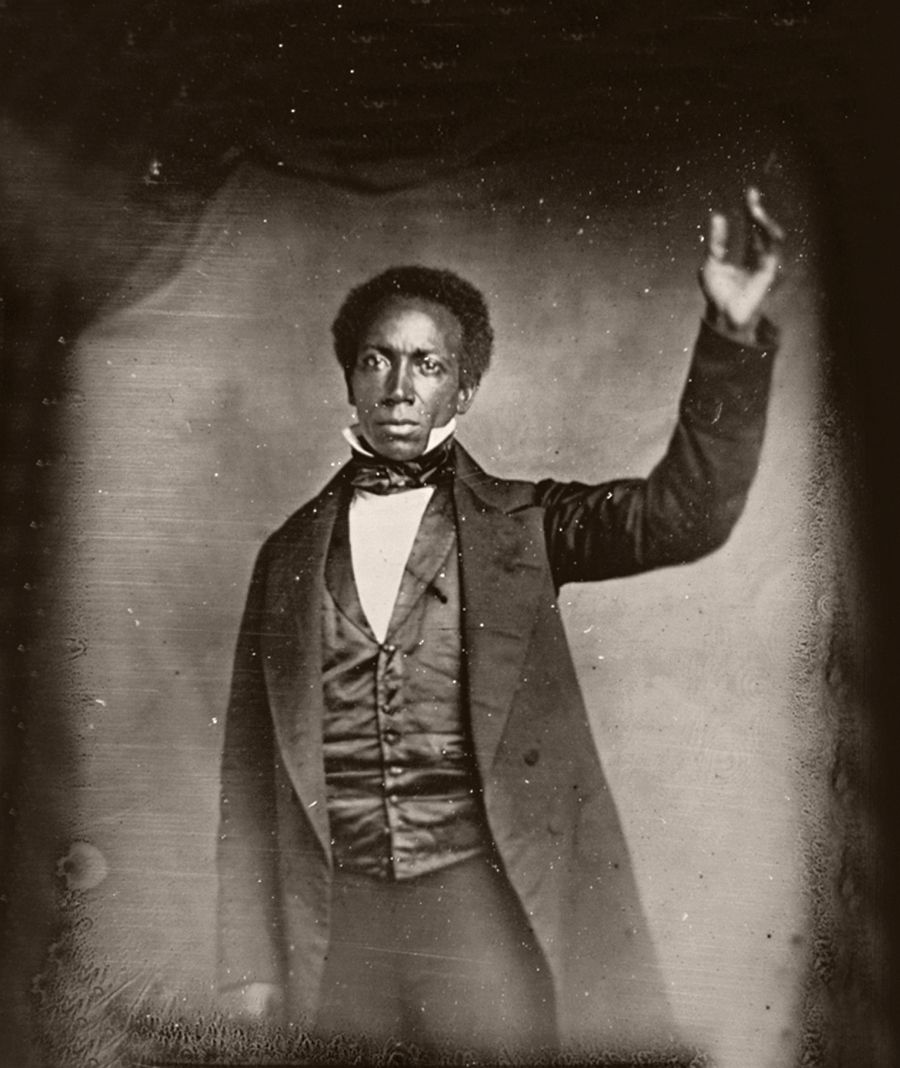

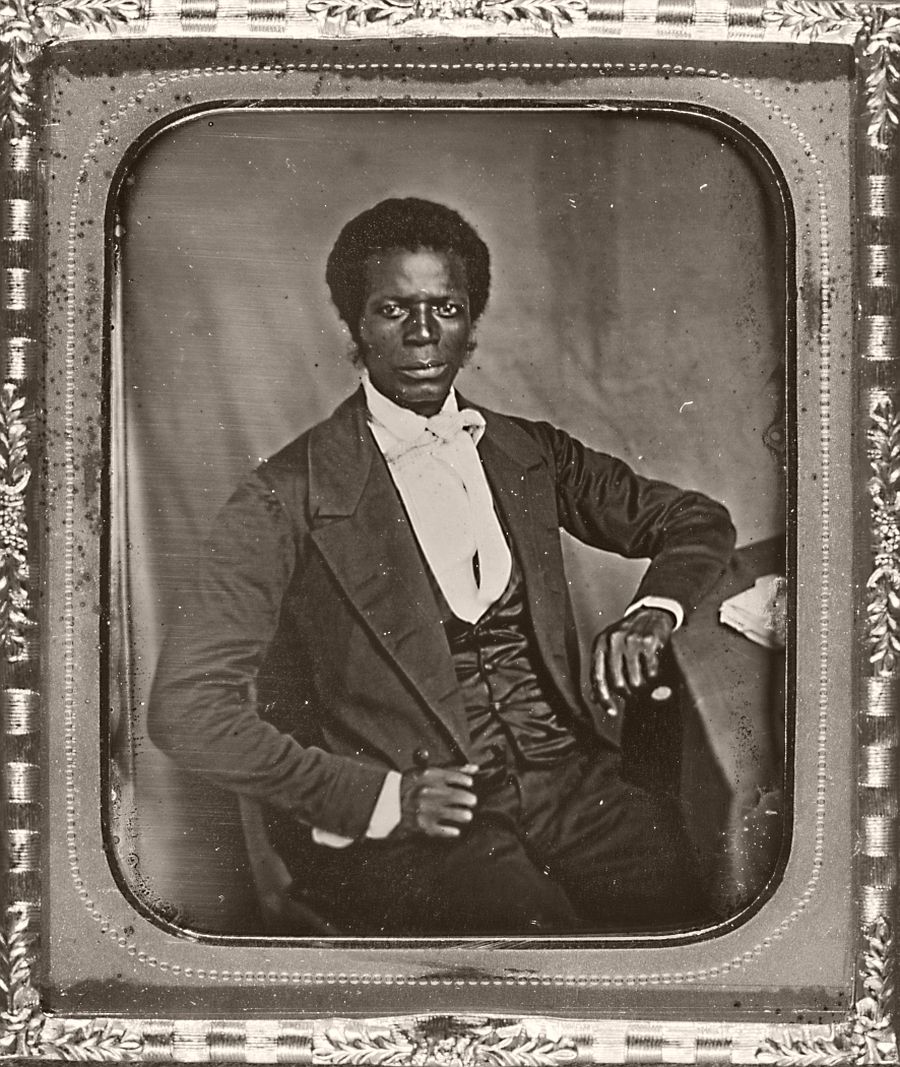

Joseph Jenkins Roberts, the first and seventh president of Liberia, 1851. Photo by Augustus Washington

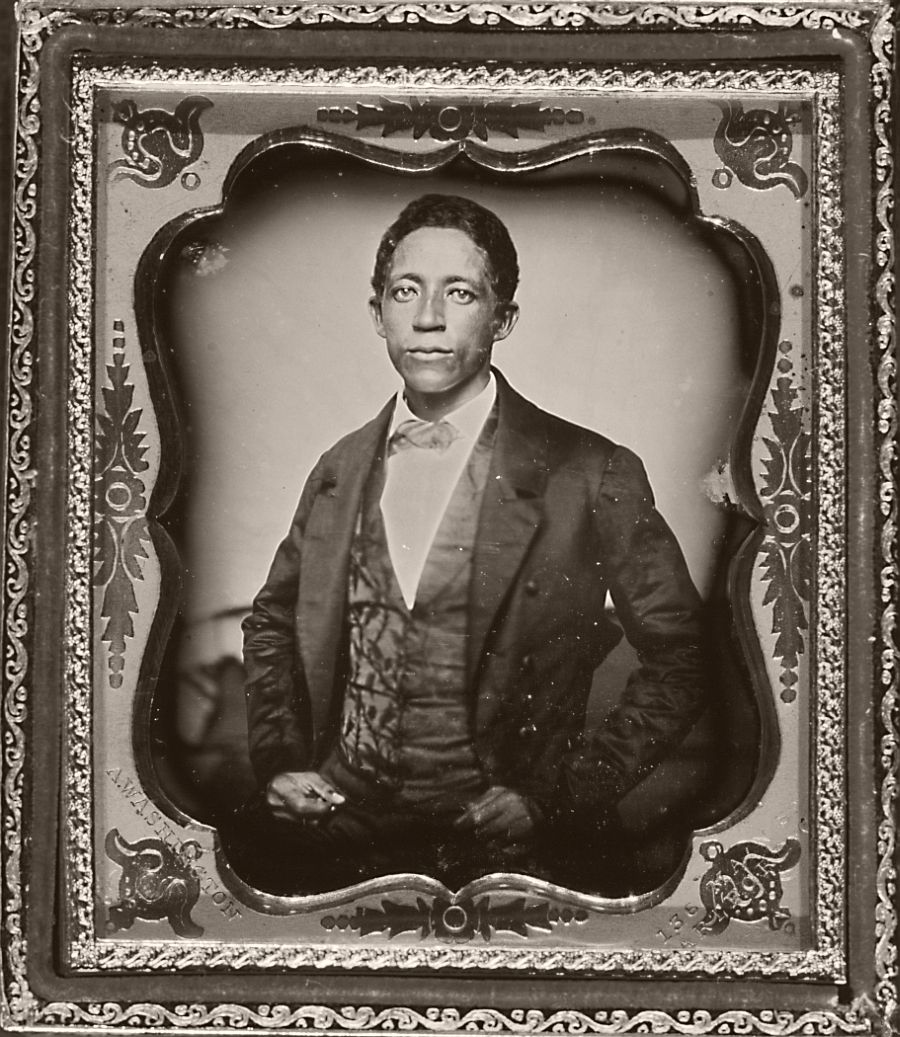

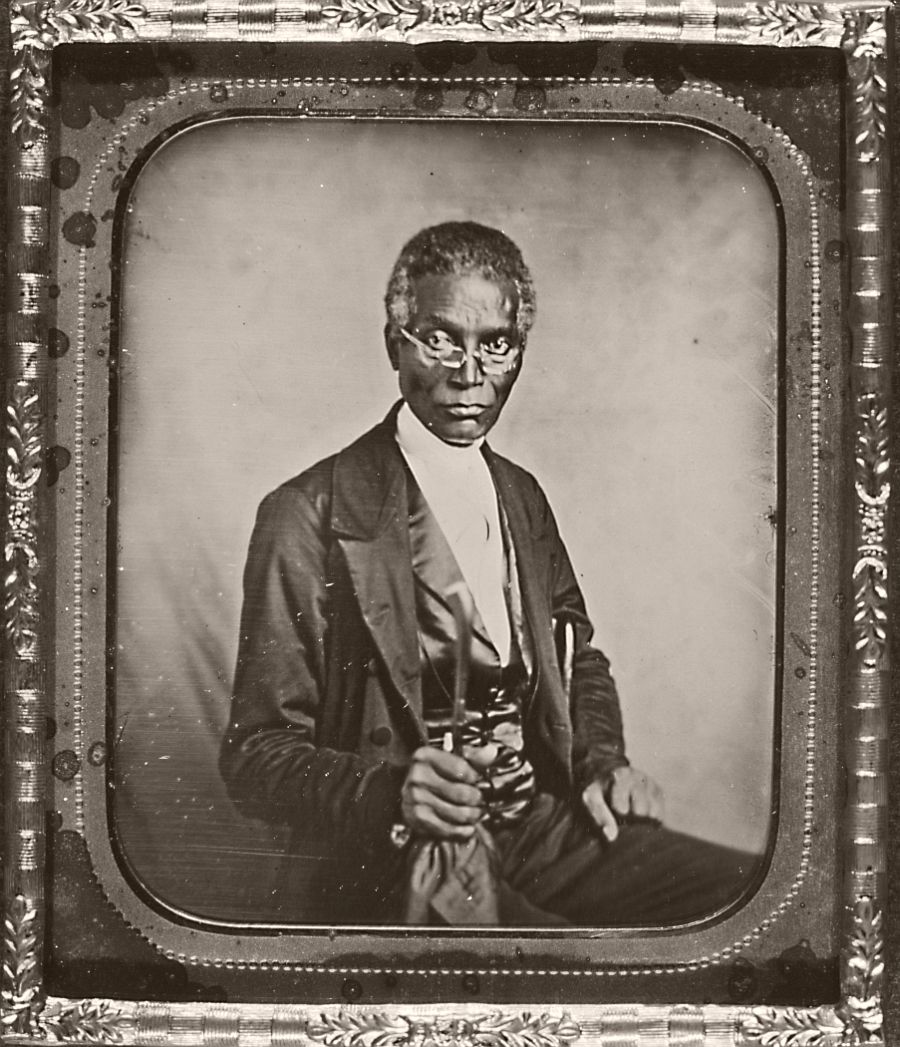

Philip Coker, clergyman and missionary of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Photo by Augustus Washington

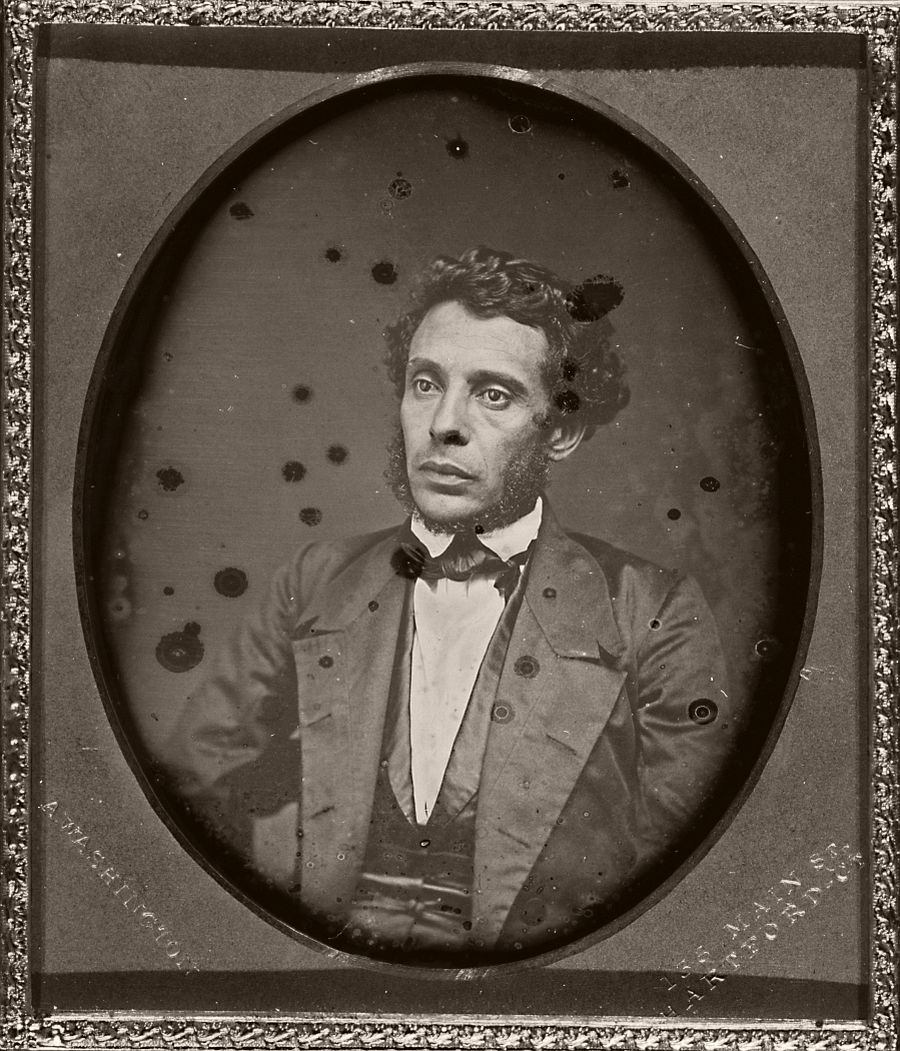

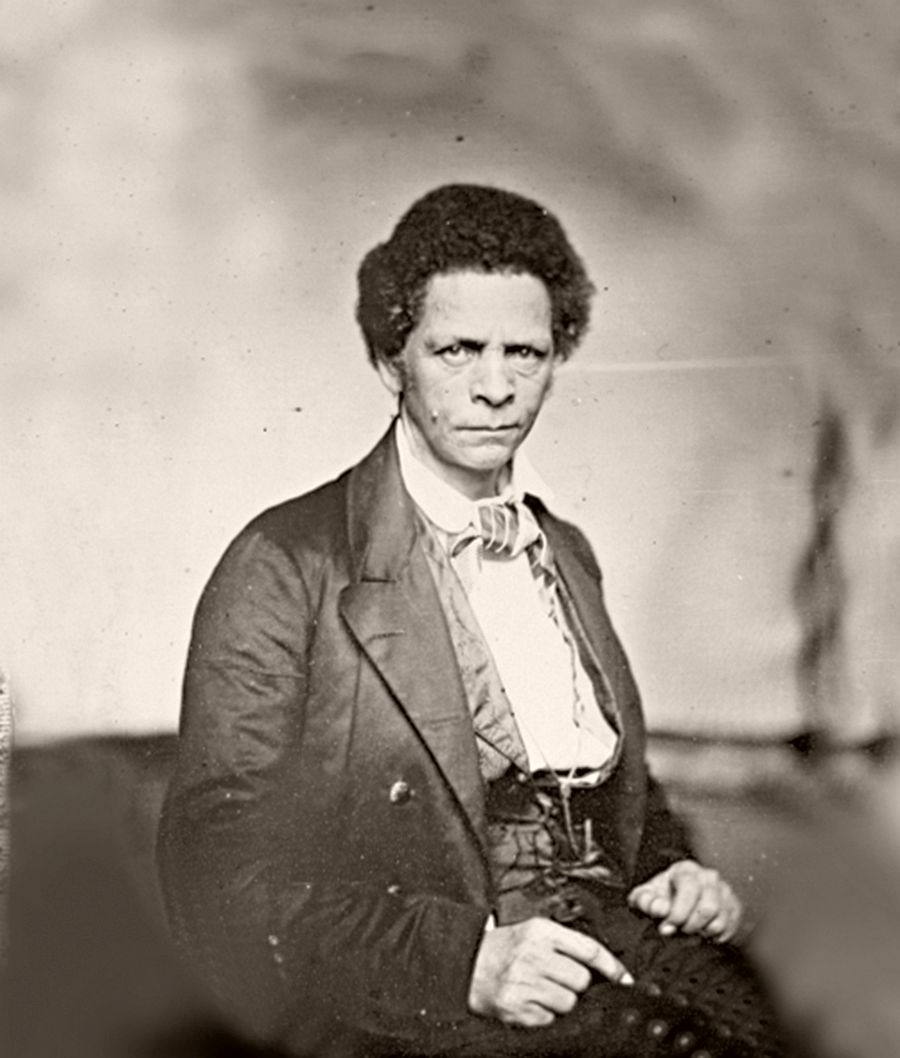

James Mux Priest, the first Presbyterian African American missionary sent to Liberia. Photo by Augustus Washington

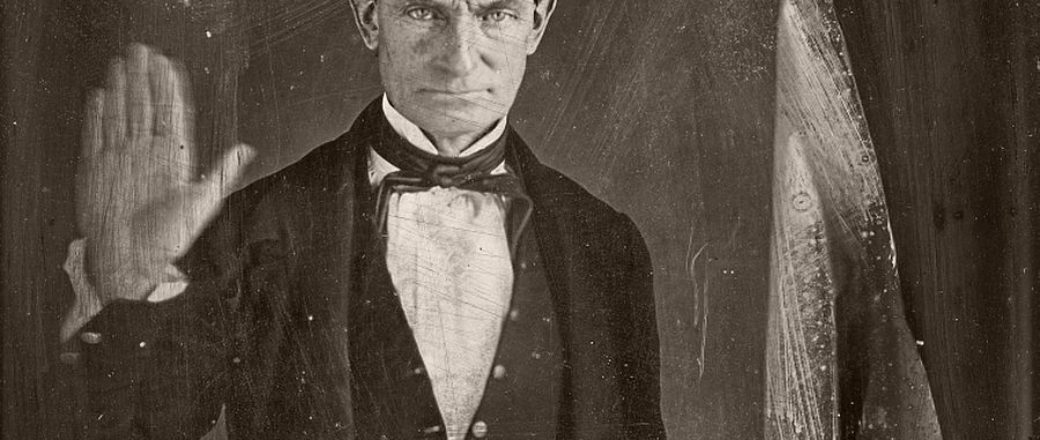

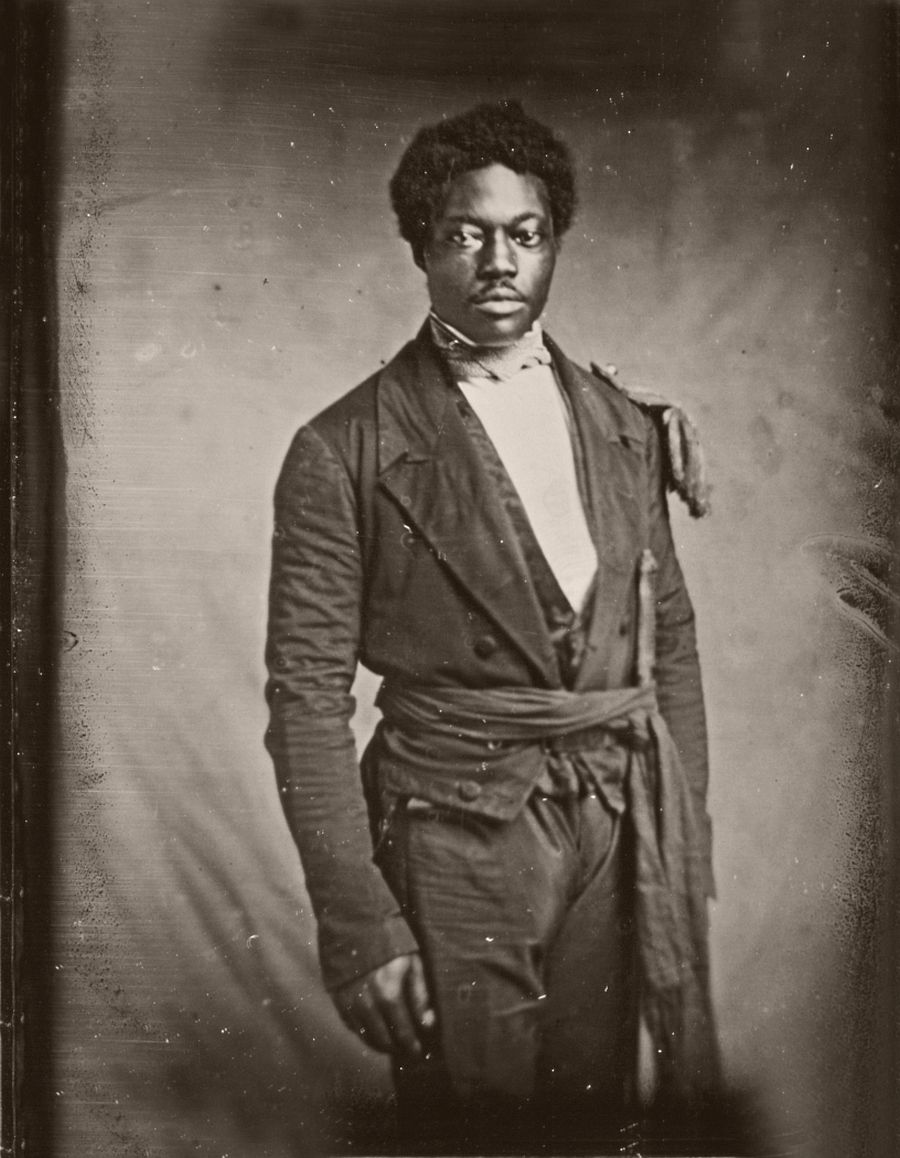

Radical abolitionist, John Brown, who believed that armed insurrection was the only way to overthrow the slavery in the United States. Photo by Augustus Washington