The original Waldorf-Astoria was among America’s first big hotels. When it was built during the Victorian era, and for years thereafter, it was considered the finest hotel in the world — and it soon became the most famous, for its reputation was carried wherever civilization had spread, and even where only explorers had gone.

The roster of its clientele has bristled from its earliest days with the names of those who have made history, who have made laws, who have made literature, no less than with those of the leaders of finance and every department of industry.

Kings and princes have made it their New York abode. The New York home of presidents and potentates, of great statesmen, great financiers and great industrialists, its prestige has never become dim.

The original Waldorf-Astoria Hotel owed its inception to William Waldorf Astor, later Baron Astor of England. To a decision of Mr. Astor, made in the spring of 1890, that he would thereafter make his residence in England, is to be attributed the building of the Waldorf — the first of the double structures of which the Waldorf-Astoria is composed.

In the winter of 1893, the Waldorf really began to come into its own. Not only had New York “caught on” to the real loveliness — back of all the sheer opulence and magnificence — of its new toy, but the rest of the country had followed likewise.

Yet, large as was the Waldorf, it was not nearly large enough. The demands upon its hospitality grew more pressing each month.

New York now was coming uptown by leaps and by bounds. Fifth Avenue as a residence thoroughfare — between Twelfth Street and Fiftieth, at least — was gone. In place of the old brownstone and red-brick fronts were coming shops — shops of high degree and of wonderful loveliness in all of their offerings — but shops nonetheless. Yet they but added to the éclat and to the prestige of the Waldorf, and to the terrific demands for rooms, particularly in the more crowded seasons of the year.

To be a room-clerk in the old Thirty-third Street office during Horse Show week or that of the beginning of the opera season was no sinecure. One had to have the wit and the diplomacy of a Talleyrand or a Disraeli — or both of them together.

In addition to all of this, there was an increasing demand upon the hotel for formal social functions of almost every conceivable sort. Mr. Bagby was organizing his Monday Morning Musicales; dining clubs, such as the Southern Society and that of the Ohio and the Sphinx Club, were fairly springing into existence, with the superior cuisine of the Waldorf always as the largest excuse for their being.

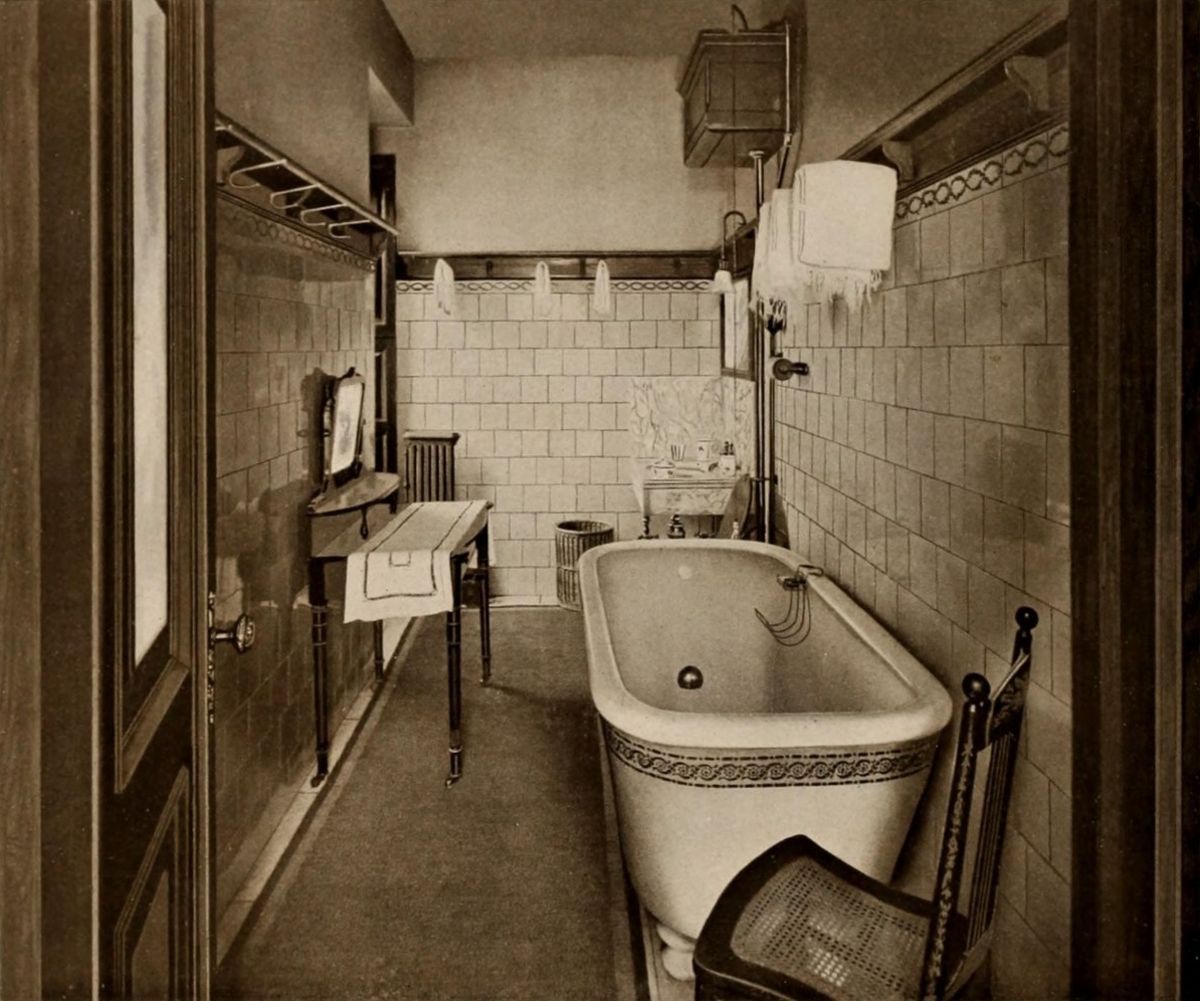

By the summer of 1896, the Astoria was well upon its way toward completion. The details of its magnificence were beginning to seep out into New York. More than the original Waldorf ever had been, this house was to be recognized as a semi-public institution. Its very coming seemed to mark a distinctive change in the urban civilization of America.

Sharp observers of our social customs began to perceive a definite tendency on the part of well-to-do folk to make their real homes in the country, coming to New York for but three or four or possibly five or six months in the winter. To cater to these folk was the special desire of the Waldorf-Astoria.

Gradually it was to become slightly less a hotel for the mere feeding and housing of travelers, and considerably more a semi-public institution designed for furnishing the prosperous residents of the New York metropolitan district with all the luxuries of urban life. With this in view, great attention was given to the planning of the ballrooms and other apartments of public assemblage in the Astoria.

The Astor Gallery alone — in the style of Louis XV and an exact replica of the historic Crystal Room at the Soubise Palace, Paris — would have been a great acquisition of itself, for any hotel. Yet it was overshadowed by the main ballroom adjoining, which remains to this day, after all these years, the most sumptuous apartment of its sort in New York, if not indeed in all America. To paint its lesser murals, Turner and Low and Simmons were summoned by Colonel Astor; for its giant ceiling, the genius of E. H. Blashfield was employed. The results speak for themselves.

via Click Americana