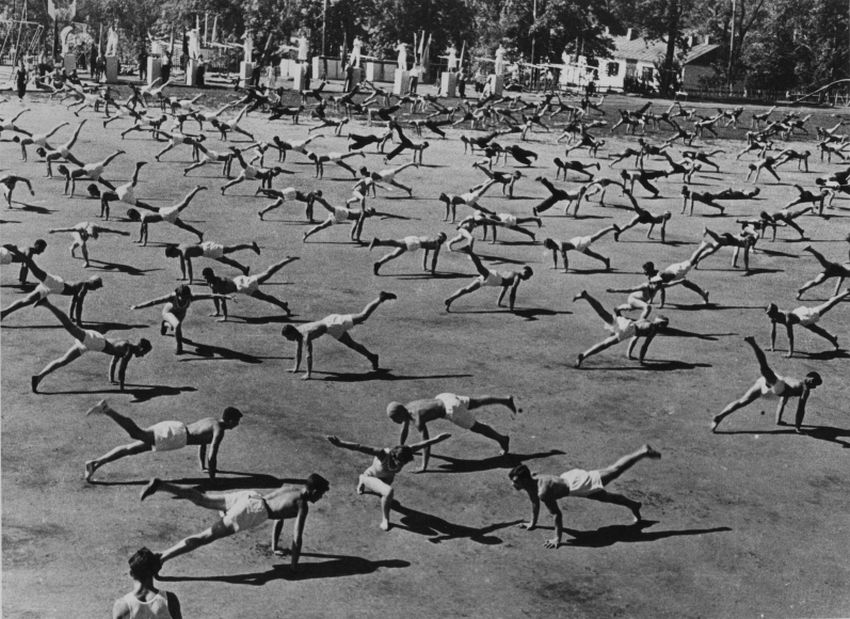

One hundred years ago this fall, the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution shook the world, changing the course of history and the fate of photography in Russia. Soviet photographers were handed the monumental task of creating a new mythology for the people of Russia, founded on striking visual symbols of collective progress, patriotism, and self-sacrifice. The result was a golden age of Russian photography in the 1920s and 1930s, marked by the emergence of experimental and constructivist photography and by the birth of Soviet photojournalism. Photographers began exploring the vast possibilities of this new medium, which allowed them to probe the complexities of multi-dimensional space; to experiment with perspectives, diagonal compositions, and close ups; to reveal the interplay between light and shadow; and to capture fleeting moments and minute details. In this way, the revolution ushered in not just a new political order, but a new vision of the country and of the world.

As photographers travelled throughout the newly formed Soviet Union, photographing industrial projects, collective farms, sporting events, cityscapes, and military parades, they were not only documenting events, but were active participants in the construction of a new reality. With advancements in printing and publishing technologies, and the subsequent proliferation of magazines, journals, and posters, images and information were able to reach the vast, largely illiterate swaths of the Russian population for whom the sight of modern machinery and massive military and athletic formations was an extraordinary revelation. Photography became recognized as the most powerful and significant propaganda tool of the nascent government.

Russian Photography after the Revolution will feature rare, large-format gelatin silver prints by Boris Ignatovich (1899-1976), a master of the Soviet avant-garde; Arkady Shaikhet (1898-1959), widely considered to be the founder of Soviet photojournalism; and Aleksandr Rodchenko (1891-1956), perhaps the most acclaimed figure in early twentieth-century Russian art and design; as well as Abram Shterenberg (1900-1979), Georgy Petrussov (1903-1971), Semyon Fridlyand (1905-1964), Sergey Shimansky (1898-1972), Solomon Telingater (1903-1969), Emmanuil Evzerikhin (1911-1984), Yakov Khalip (1908-1980), and Georgy Zelma (1906-1984).

Russian Photography After the Revolution

September 7 – November 4, 2017

Nailya Alexander Gallery

41 East 57th Street, Suite 704, New York, NY, United States

nailyaalexandergallery.com

Arkady Shaikhet (1898-1959). Express, 1939. This photograph is an embodiment of dynamism, a symbol of the new Soviet society moving towards a bright future. The steam conceals the wheels and the engine appears almost like a dirigible about to take off. The sky is superimposed for a more dramatic effect. Published in Soviet Photo #2 in 1940, this photograph became one of the greatest achievements of Soviet photography. Soviet design in the late 1930s cannot be imagined without the Soviet metro, aviation and this Express engine.

Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956). Portrait of Mother, 1924. This is one of the first Rodchenko’s photographs, a compelling portrait of his mother who learnt how to read in her late years.

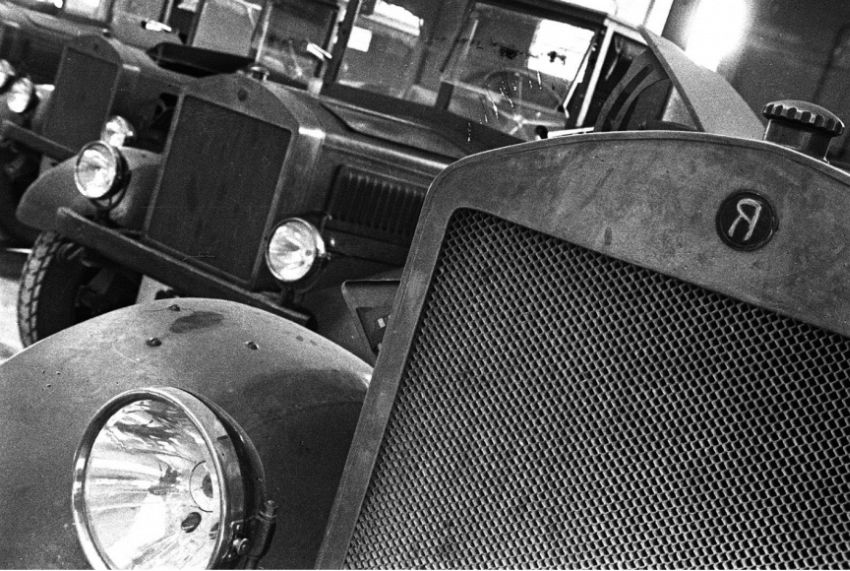

Boris Ignatovich. Our First Cars in the Garage of Mossel’prom, 1933. YaG-3 five ton trucks from Yaroslavl’ Automobile Factory

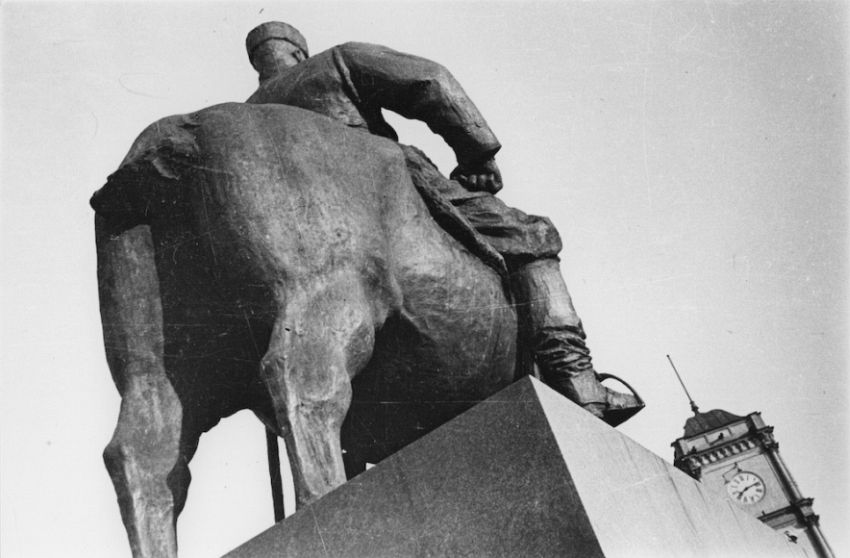

Boris Ignatovich (1899-1976). Scarecrow, 1927. In 1909, monument to Alexander III was erected in the center of Znamenskaya Square (present day Vosstaniya Square) in front of the Nikolaevsky Railway Station, in recognition of the Tsar’s construction of the Great Siberian Railroad, which connected the capital with the Far East. The monument was designed by Italian sculptor Paolo Trubetzkoy (whom G.B. Shaw declared “the most astonishing sculptor of modern times”). After the 1917 revolution, a poem by Demyan Bedny, “Scarecrow,” was carved into the pedestal. In 1937, the monument was moved to the yard of the State Russian Museum, and now it stands near the museum’s Marble Palace.