In 1869 The Emperor was restored to nominal supreme power, and the imperial family moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo (“eastern capital”). However, the most powerful men in the government were former samurai from Chōshū and Satsuma rather than the Emperor, who was fifteen in 1868. These men, known as the Meiji oligarchs, oversaw the dramatic changes Japan would experience during this period. The leaders of the Meiji government, who are regarded as some of the most successful statesmen in human history, desired Japan to become a modern nation-state that could stand equal to the Western imperialist powers.

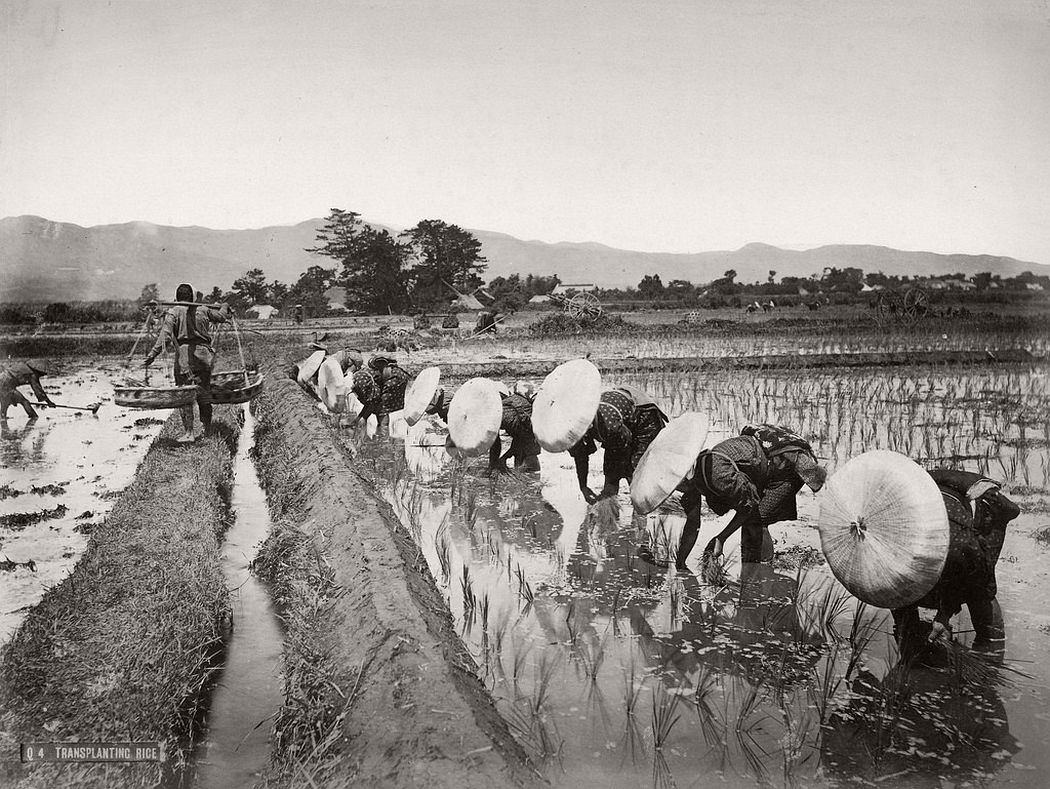

The Meiji government abolished the Neo-Confucian class structure, and replaced the feudal domains of the daimyōs with prefectures. It instituted comprehensive tax reform and lifted the ban on Christianity. Major government priorities included the introduction of railways, telegraph lines, and a universal education system. The Meiji government promoted widespread Westernization and hired hundreds of advisers from Western nations with expertise in such fields as education, mining, banking, law, military affairs, and transportation to remodel Japan’s institutions. The Japanese adopted the Gregorian calendar, Western clothing, and Western hairstyles.