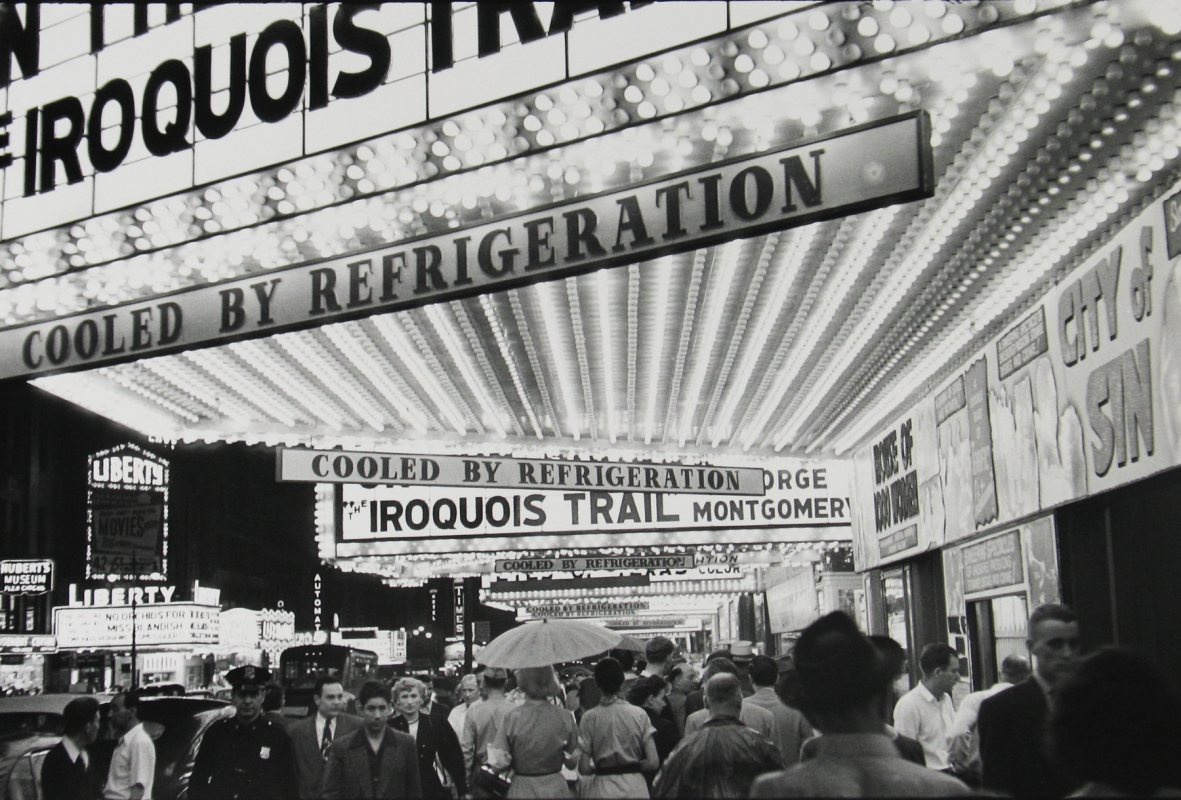

Born in 1916 to immigrant parents from the Russian/Polish border, Louis Faurer’s childhood, in a South Philadelphia neighborhood of mostly Italian and Jewish immigrants, was not easy. “There were problems of survival,” he once said. After graduating from the South Philadelphia High School for Boys in 1934, he spent a few summers as caricature artist in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Inscriptions of all sorts fascinated him, and he began studying at Philadelphia’s School of Commercial Art and Lettering in 1937. He also worked freelance–painting advertising signs and lettering posters.

That same year, Faurer purchased his first camera, a used 35mm Kodak Vollenda, from his friend Ben Somoroff. Shortly thereafter, he won a prize in a weekly photo contest of the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger. “I suppose when that happened,” he said, “I was convinced, positively, concerning my future course.”

Somoroff, who was studying graphic design at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (now the University of the Arts), introduced Faurer to a number of photography students at the school, many of whom became his lifelong friends and professional collaborators. Unlike his friends, however, Faurer never attended classes in photography, except for a brief course he took in the military (from 1941-1945, he was a civilian photographer for U.S. Army Signal Corps, Philadelphia).

In the late 1940s, Faurer and several of his colleagues from Philadelphia opened studios in New York. Like many photographers of his generation, Faurer sought employment working for magazines, but unlike his photojournalist peers, who pursued careers at such publications as Life magazine, he gravitated toward fashion photography. In 1947, Lillian Bassman, the first art director of the short-lived Junior Bazaar (later incorporated into Harper’s Bazaar), invited him to join the magazine’s staff. The new magazine also hired Robert Frank, a recent immigrant from Switzerland, and the two immediately struck up a friendship that would last for fifty years. About their work, Faurer commented, “We influenced each other, without any tension, with total acceptance. We never spoke about the images. . . .We never criticized each other. We influenced each other without jealousy and without resentment.”

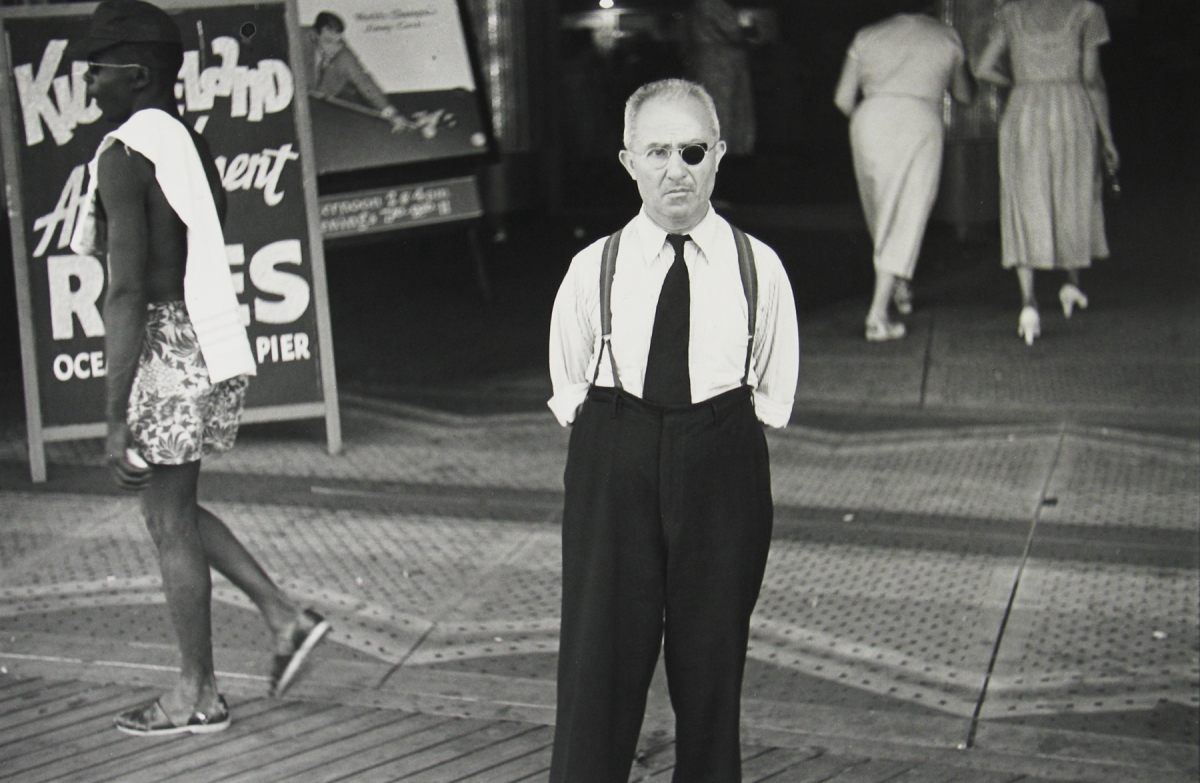

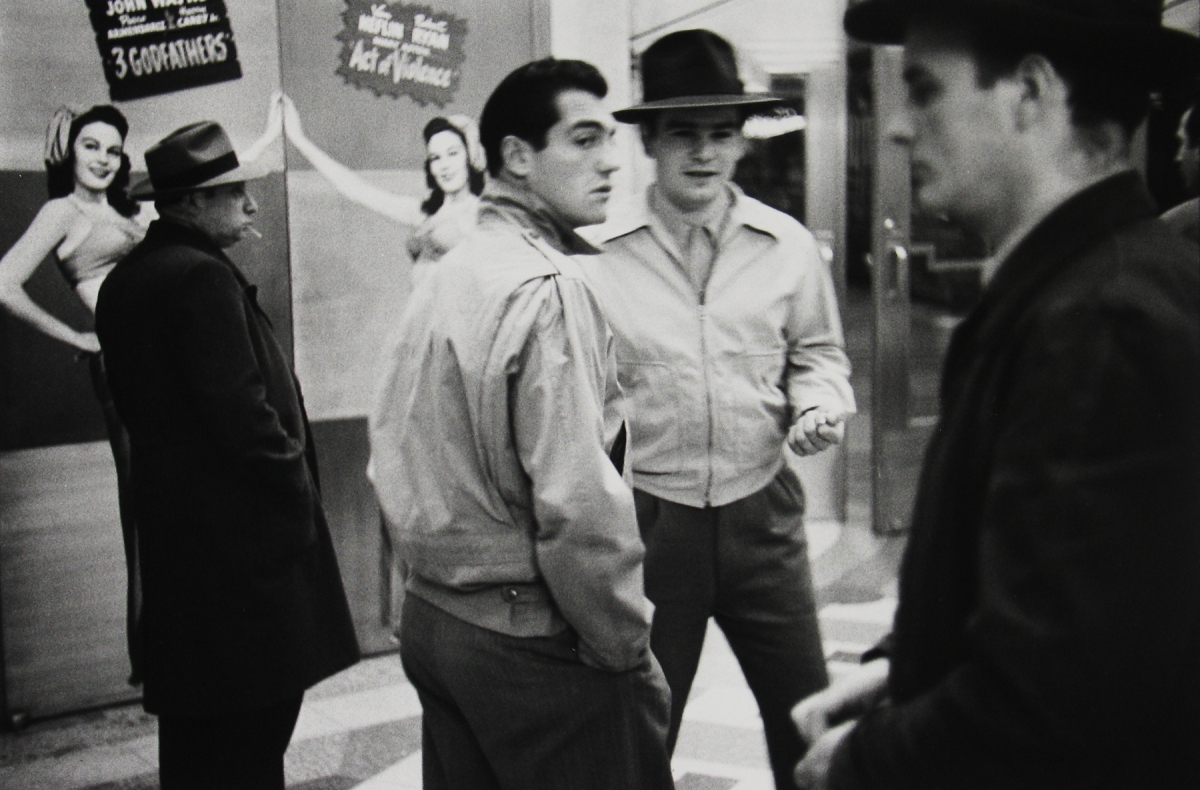

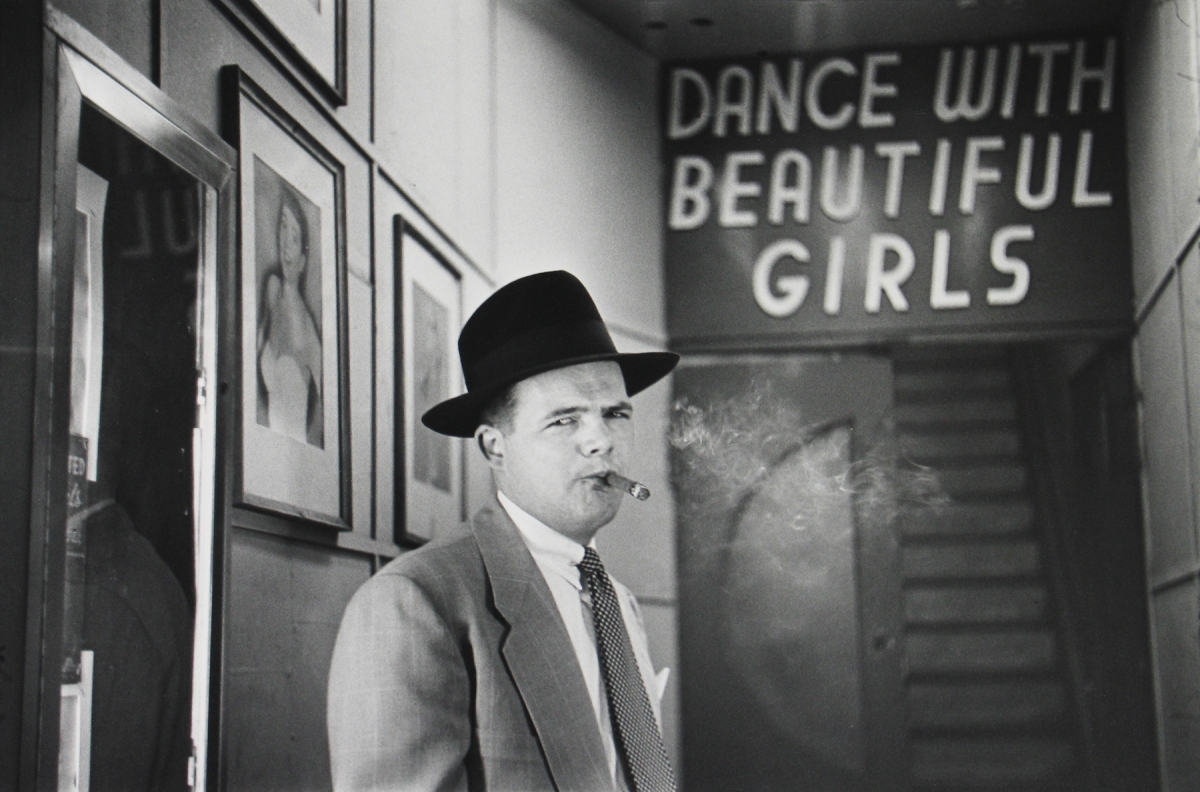

Between 1946 and 1951, Faurer built his professional career while continuing to work intensely on his personal photography. He walked the city at all hours, knew it well, and found endless subjects to photograph. With sensitivity, sympathy, and originality, he chronicled the New York urban environment and its inhabitants. The trip from Philadelphia to New York was the most important journey he ever made. “New York,” wrote curator Walter Hopps, was “where he stayed, and where his vision encompassed the all of it, both ordinary and odd.”

Faurer was a key member of the New York School of street photographers active from the 1930s to the 1950s. A loosely defined group that included Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, and William Klein, the New York School chose city life as its subject, preferred 35mm cameras, and rejected traditional documentary styles. As one historian stated, they “fostered an indisputably American aesthetic–reckless, vulgar, just shy of anarchic.” By the early fifties, Faurer had been using reflections, double exposures, and sandwiched negatives for more than a decade to convey the complexities he perceived in city life.