It is not my purpose to present you my resume or to teach you anything. You could learn the technical aspects of photography from YouTube videos. Don’t ask me what tools I use. Don’t ask me about aperture, lenses, camera bags. I would like to talk about silence, passion and beauty, about poetry and its opposite – pornography. I would like to talk about fear and creativity, about history and ultimately about mortality. I am suggesting that we need to learn how to see again.

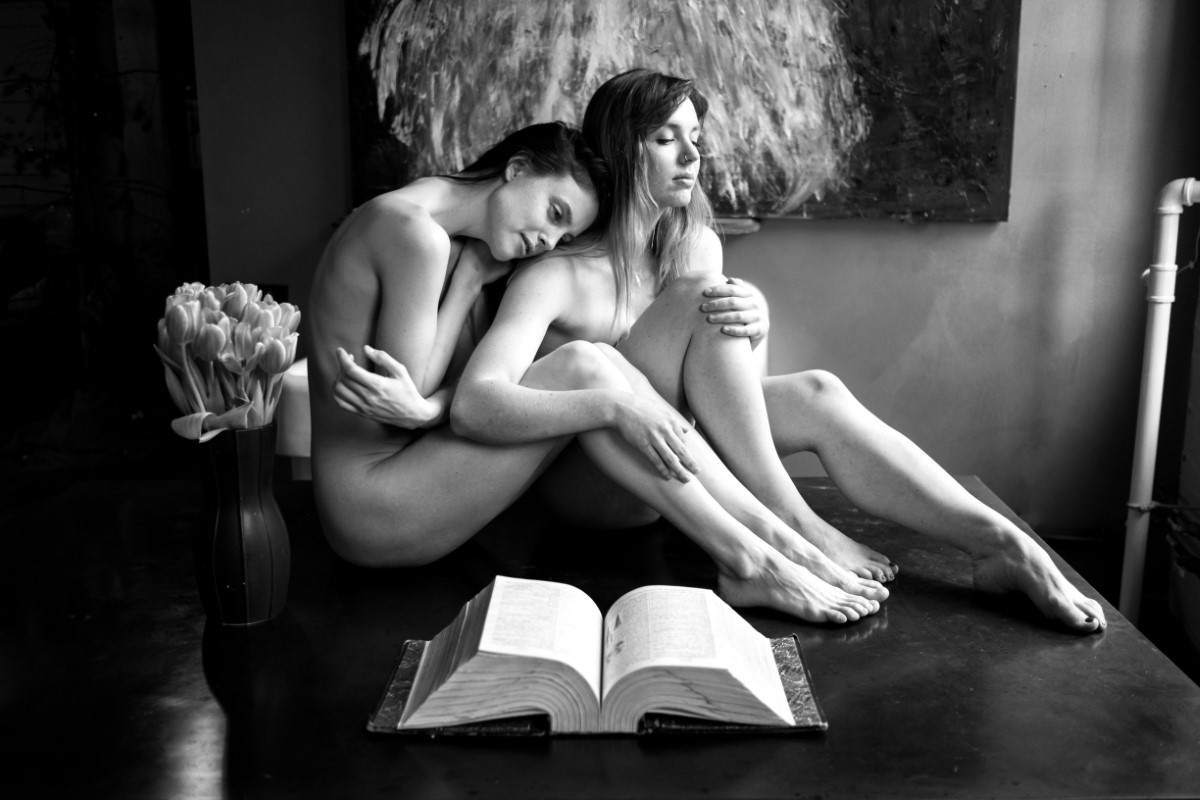

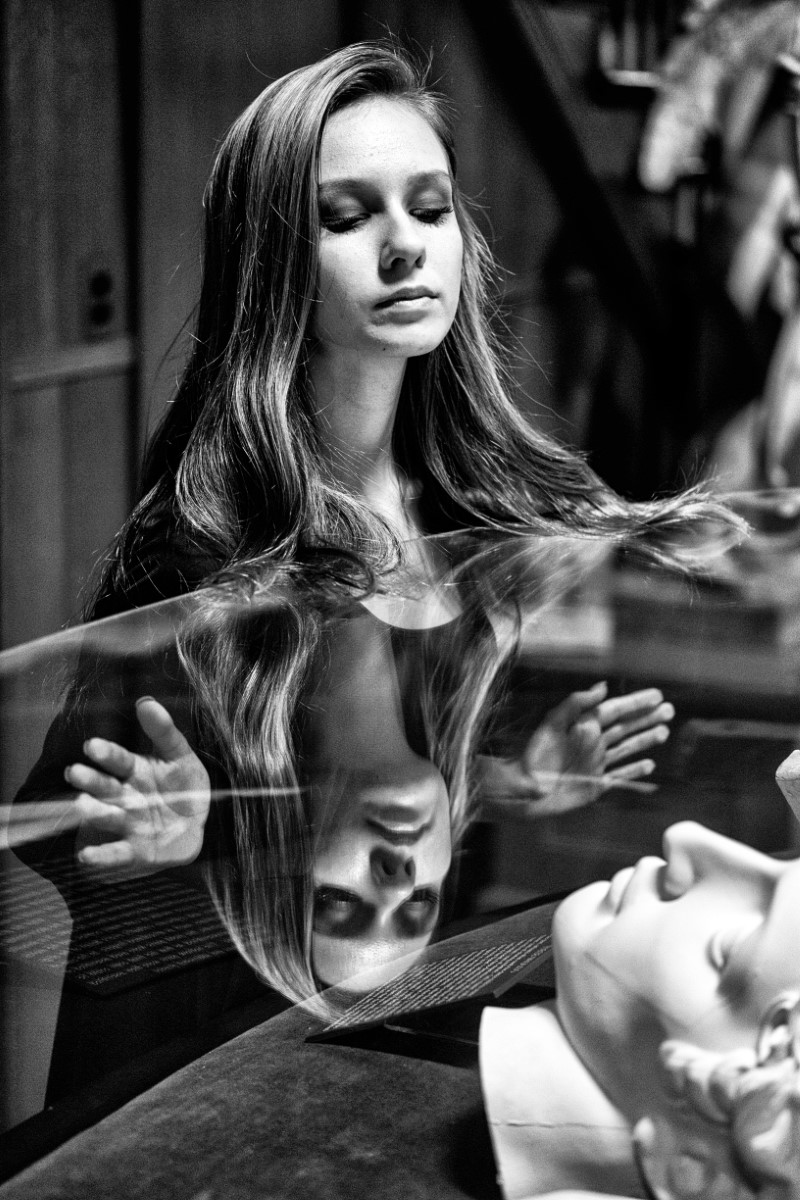

Like some photographers, I am interested in Truth and Beauty. I am interested in quietude, in making the viewer spend some time in front of an image and become a partner in the process of seeing. The function of art is not to escape reality, but to help us experience it more completely. My current work is about perception, about memory, and the equivocal nature of experience. I am a humanist in a world where terrorists blowing themselves up in public places have become footnotes in the daily news. I am the opposite of a terrorist in the sense that I am trying to hold space for the Body. I am the restorer in an archeological dig. Being a humanist has much to do with my desire to bring a little balance into the world. I am fortunate that my destiny involves pressing a shutter release button and not pulling the trigger of a machine gun. I believe that art should be a positive force.

Lately, my eyes have been plowing through the debris of vulgarity the way strong ice breaker ships slice their way through the thick ice blanketing rivers in the winter. The waters are polluted these days with so much meaninglessness, and Beauty has become unexpected, surprising. We visit museums and galleries, monuments and gardens, we walk around busy streets, quiet fields, food markets, parks and castles, stopping only occasionally for echoes of Beauty. Could we still talk about Beauty after Auschwitz, Hiroshima, and 9/11? Are we still allowed? Of course. We have a duty – the duty to point out our lenses in the direction of what makes us whole, in the direction of what makes us better. We have a duty to create silence.

This is where photography as an art form comes in. Photography wasn’t born out of the desire to make art, but out of the need to have proof of our physicality and the physicality of the world. In the end, photography ended up being as illusory as the other art form (painting) that it was intended to replace. Ironically, since the world’s main pastime became (one more time) pleasure, and since we cannot live without the constant affirmation of the Self, noise has become photography’s constant companion. Photography is a form of pollution.

In a church in Siena, I once saw a wall crowded with saints, their eyes removed with swords or chisels by eager iconoclasts. The fresco reminded me of the Romanian churches of Bucovina, where similar images could be found; in that case, the eyes of the Christian saints were removed by the swords of the conquering Ottoman armies. In Greek, “Iconoclasm” translates as “struggle against images”. The history of art is in a way the history about this continuous loud struggle between pleasure and history. History is a necessary evil and always noisy. Pleasure disables seeing.

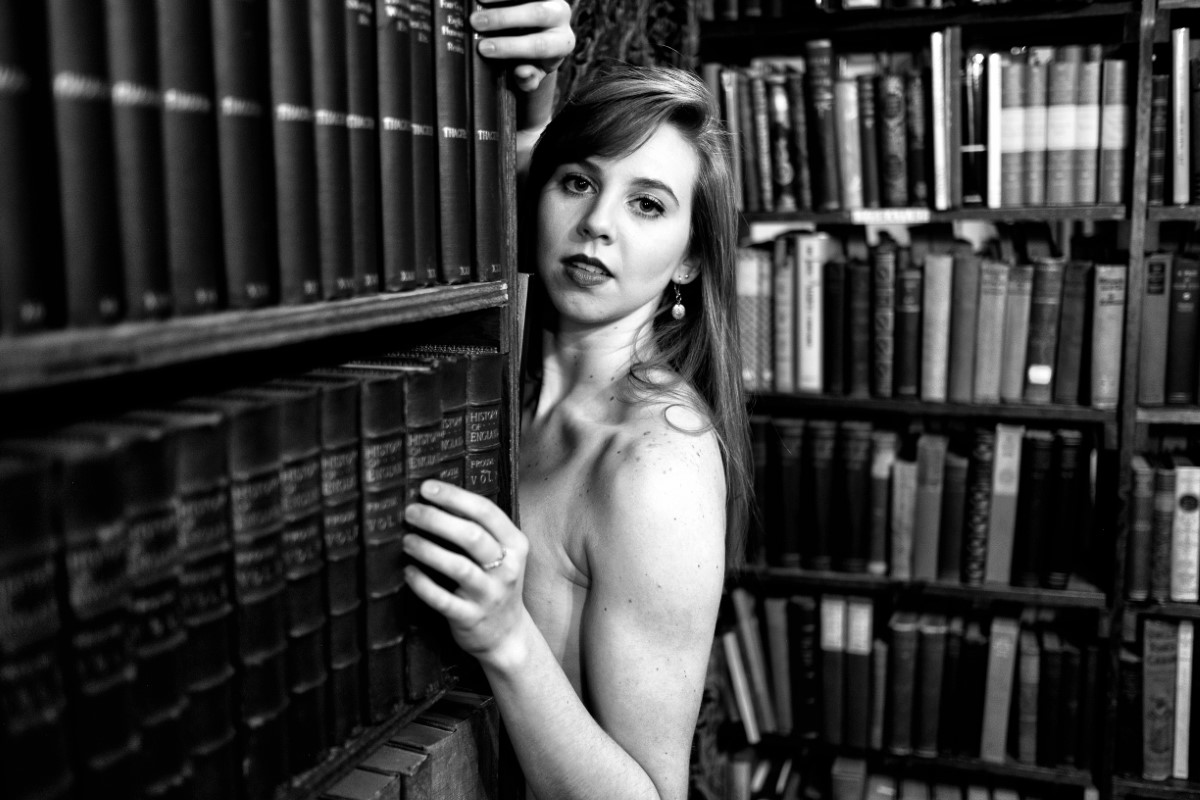

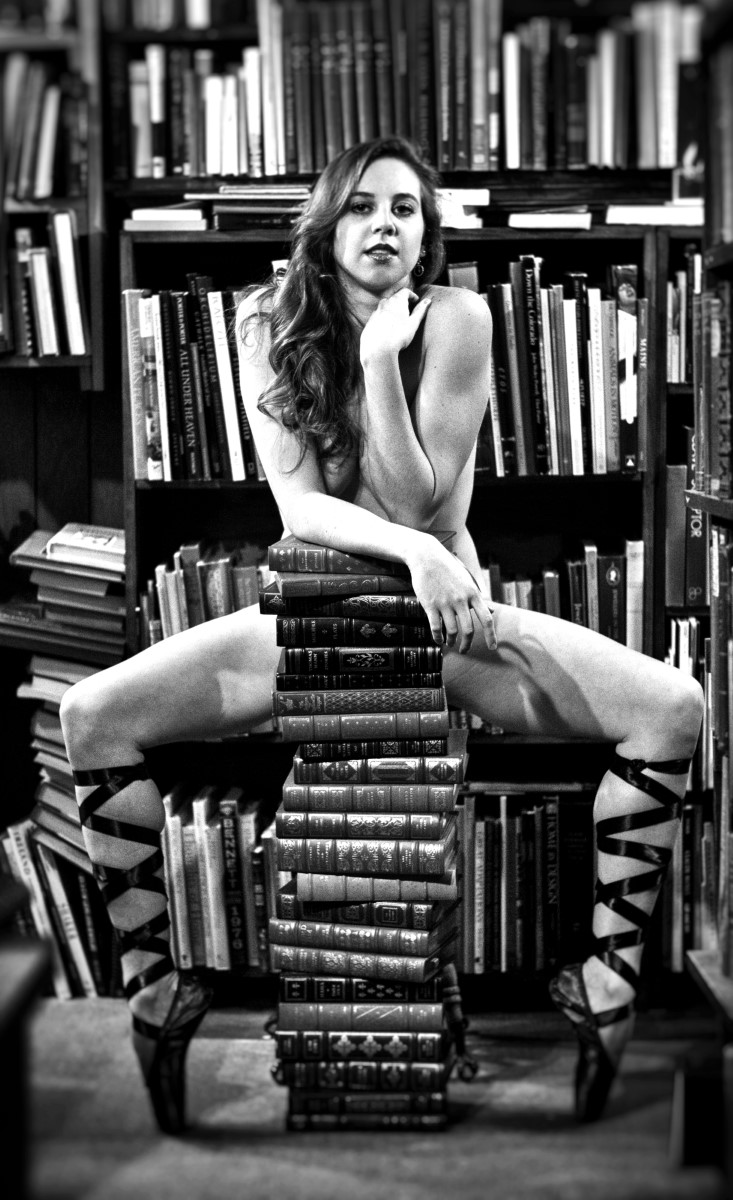

From where I stand, photography should lead us to silence, away from the assaults of empty images and empty words. Silence has mainly disappeared from our existence, except for when we look at art. I walk around looking for meaning in things and places that have no apparent meaning. I walk around looking for images that would be appropriate portals to God (by God meaning that supreme state where a real understanding happens, a major revelation of essential truths). How pretentious to think that one could get anywhere near that! Isn’t it too much to ask? To understand and to connect? To embrace and to weep in wonder at the Beauty surrounding us?

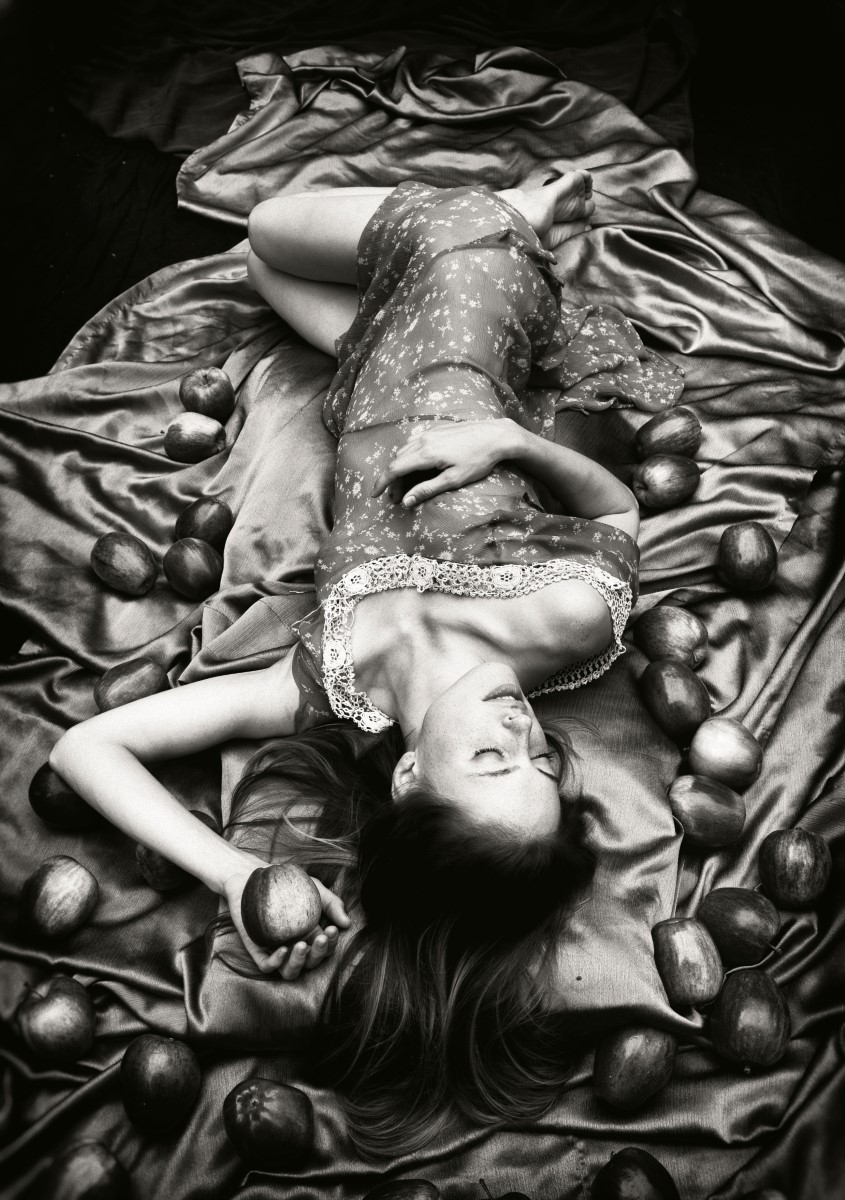

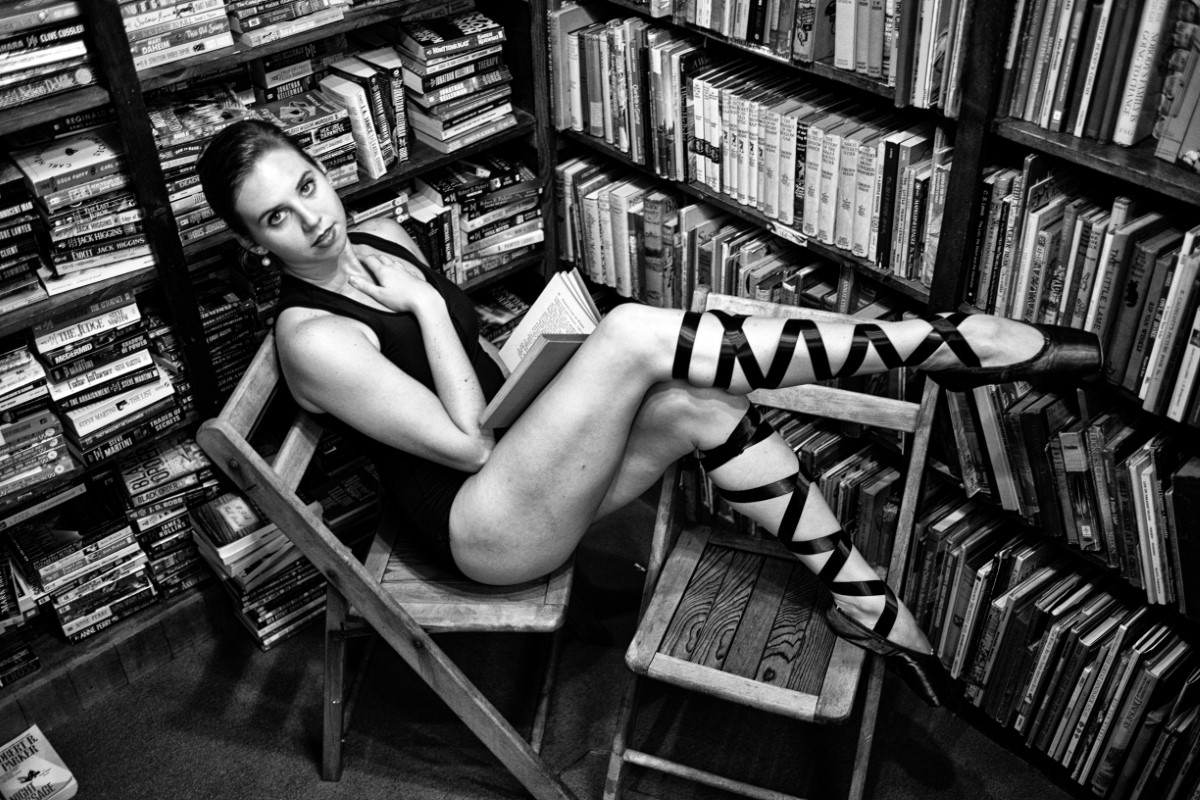

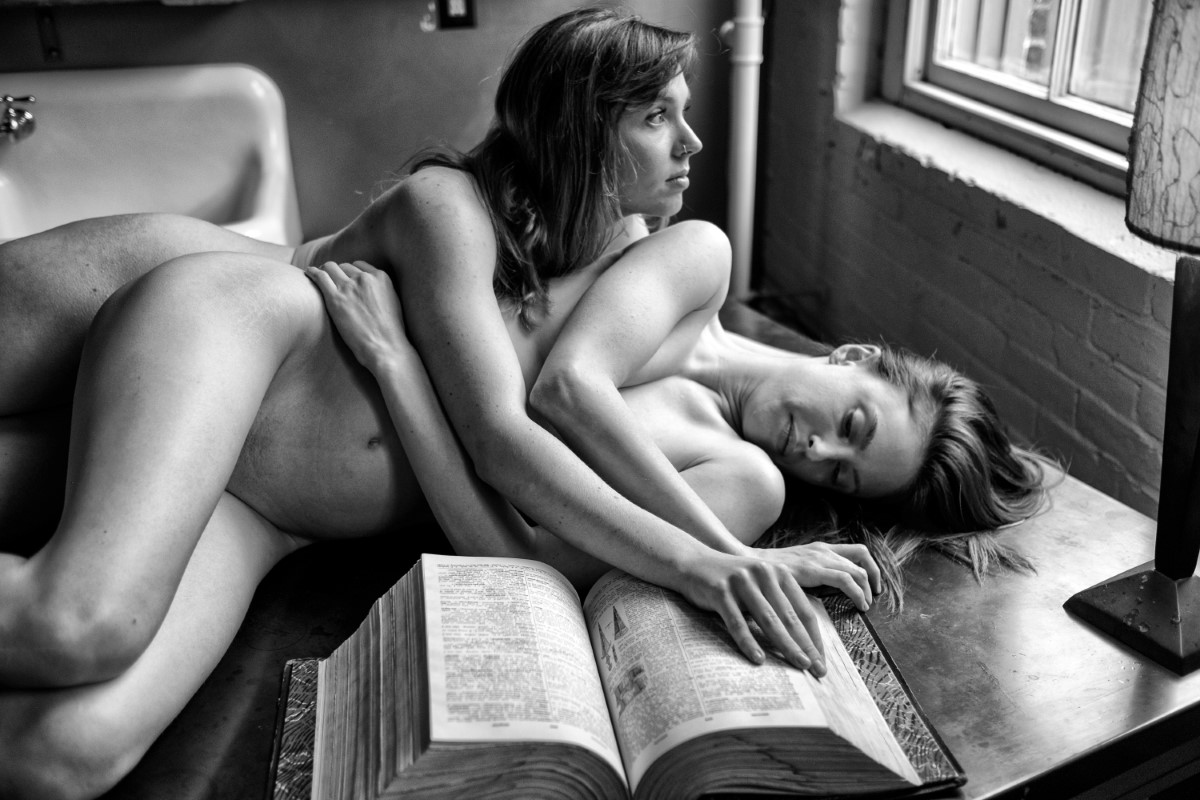

Is it strange to look for silence in the Body? I have been photographing the human figure for a few years now. I am interested in the subject for several reasons, one being mortality. Bodies and portraits have their own history. They are mysterious planets. They relate to each other in a cosmic way. They have their own logic and their own politics. From the endless images of the Christ on the cross to the voluptuous women in Rubens’ canvases, the Body has always been political. It is only lately that our bodies have been stolen by the Guilt Police. It’s our own fault. Somehow we managed to extract the sacred and the beautiful out of our physicality and reduce the Body to its basic functions: a machine designed for producing our latest electronic drugs and for perpetuating our species. When did the human machine lose its main propeller – the soul? When did we lose our bodies? I once saw a few tourists speeding through the gallery at the Metropolitan Museum of Art where Greek and Roman statues were being exhibited. The visitors (a couple and their two teenage daughters) avoided looking at the magnificent works by shielding their faces with folded maps. What a horror. If you look at those statues depicting (mostly) male athletes or gods, their marble penises are often missing. The conquerors would take a hammer at what was perceived as the (always male) centers of power – no difference here between the missing penises and the missing eyes of the Tuscan saints. The Western World has always been terrified of both, and the Church always led the way in censorship. For a while, until the invention of the printing press in the 15th century when pornography changed our vision about the human body, the Virgin Mary was allowed to show an occasional nipple. The Western mind was still pure; breastfeeding was God’s connection and gift to the world. But then, all that changed; reality was replaced by fantasy. We were made to believe that it is more accurate for cherubs painted on church ceilings to have a set of fluffy wings on their backs instead of sexual organs. That’s when images of the Crucifixion became more popular and replaced the images of the breastfeeding Virgin. We sanitized the physicality of birth with all its pain and blood and replaced it with the physicality of torture. That is why today we are offended by women breastfeeding in public spaces, but we find it okay to watch ISIS decapitation videos on YouTube. Birth became a sin, while the Crucifixion became a routine occurrence.

Inspected, dissected, mocked, reevaluated, our physical selves became the beginning of a battle among church, society and science. This didn’t start with Adam and Eve being kicked out of the Garden of Eden, but with the surge in autopsies. (Interesting that autopsia means in Greek: “the act of seeing for oneself.”) The reason we have pornography today is because we were curious to find out if God resided inside us. We didn’t know it at the time, but what we did was the equivalent of demolishing a church in order to find out if the hollow space inside its domes was truly sacred.

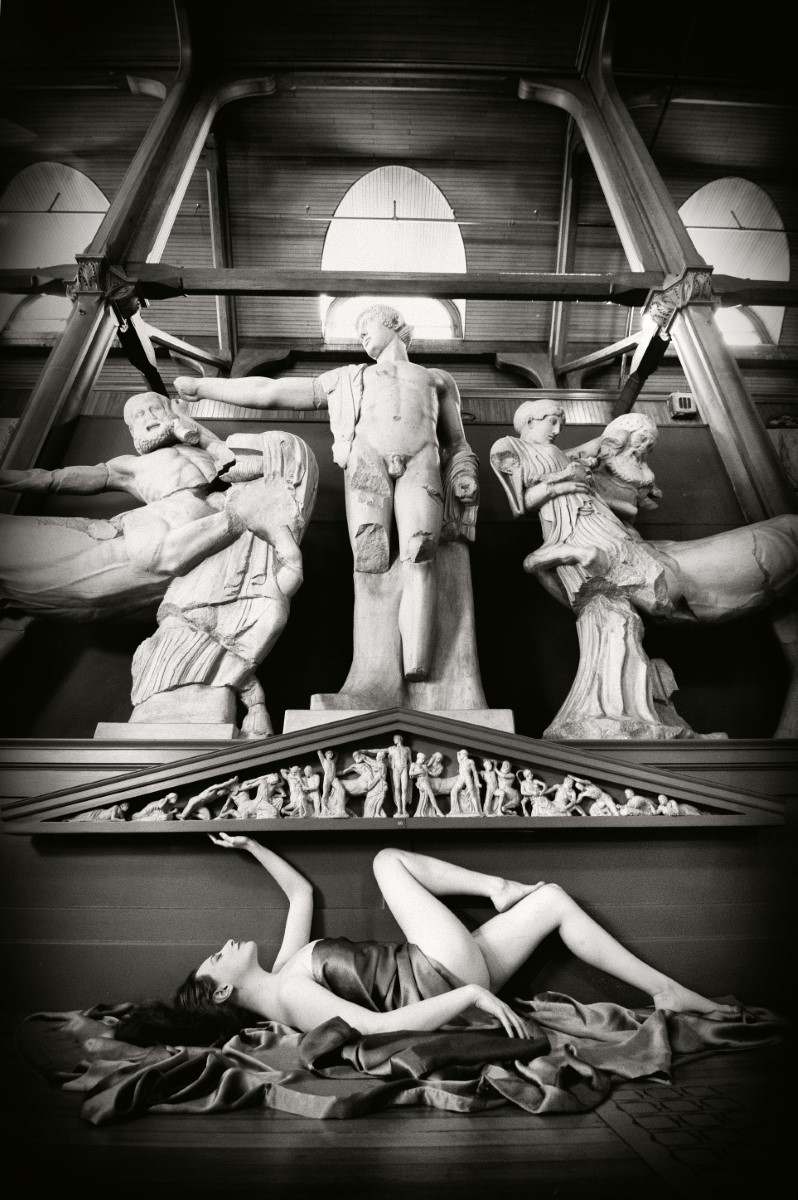

In museums, nudity has been accepted mainly because of its connection with mythology. It is safe to hide behind mythology in order to disguise the true reasons for our fears and desires. These days, in art museums all over the world, the statues and the paintings laugh at us. They understand us better than we understand them. Photographs, paintings and statues are the last repositories of complete silence. After the death of the statues we will only have silence and images.

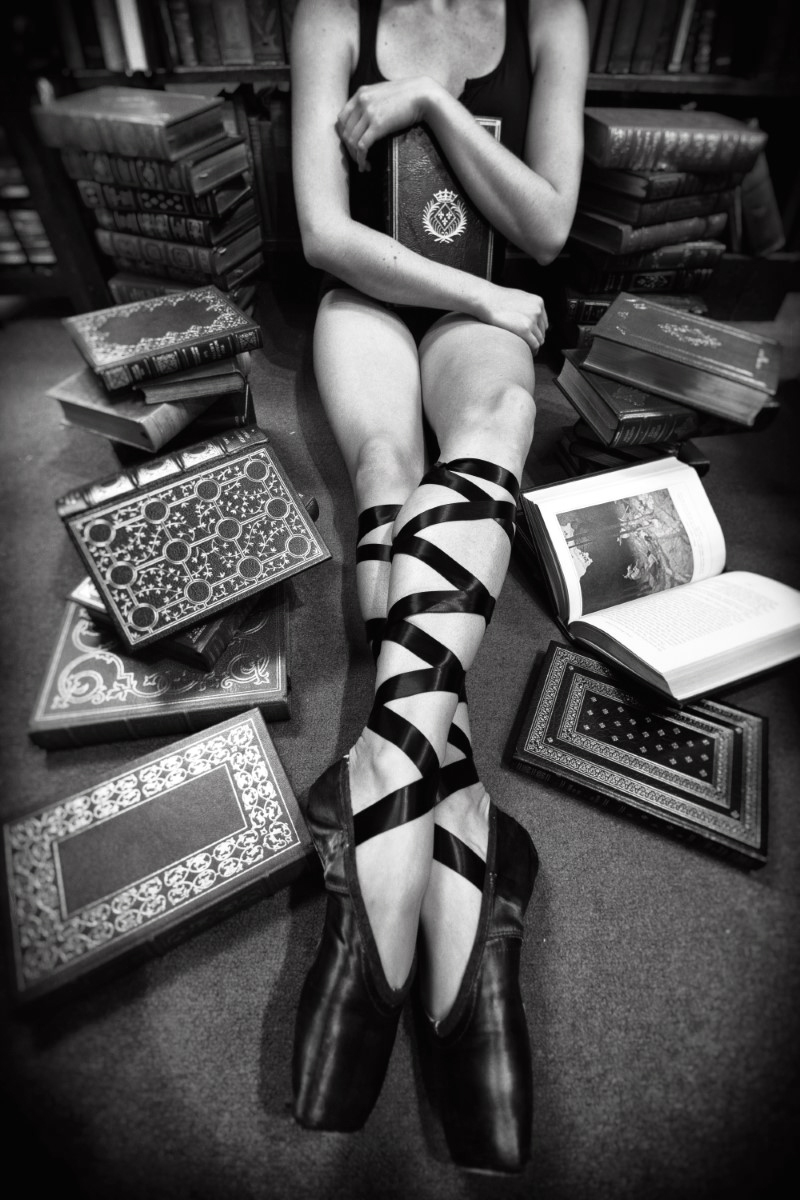

On the other hand, the Body needs to achieve nothing. In a perfect world, all gyms should be suspect. In a perfect world, any body should claim its place on a pedestal. We are afraid of nudity because we are disconnected from our selves. We are closing our eyes while looking at ourselves naked in mirrors because we are afraid of death. What we need to learn from the marble bodies of statues and sprawling nude paintings in the world’s museums is that our physical existence has a continuum the way our spiritual existence does. If you are an artist working in photography, you will never take a photograph of a nude woman tied with ropes, wearing a gas mask in front of a Christmas tree, or showing a gun in her mouth. All this comes from a primeval violent instinct toward women that has been perpetuated by the media in all sorts of ways, from the original King Kong movie to contemporary advertising. Nudity is always silent. Pornography is always loud. Any image lacking poetry is pornographic.

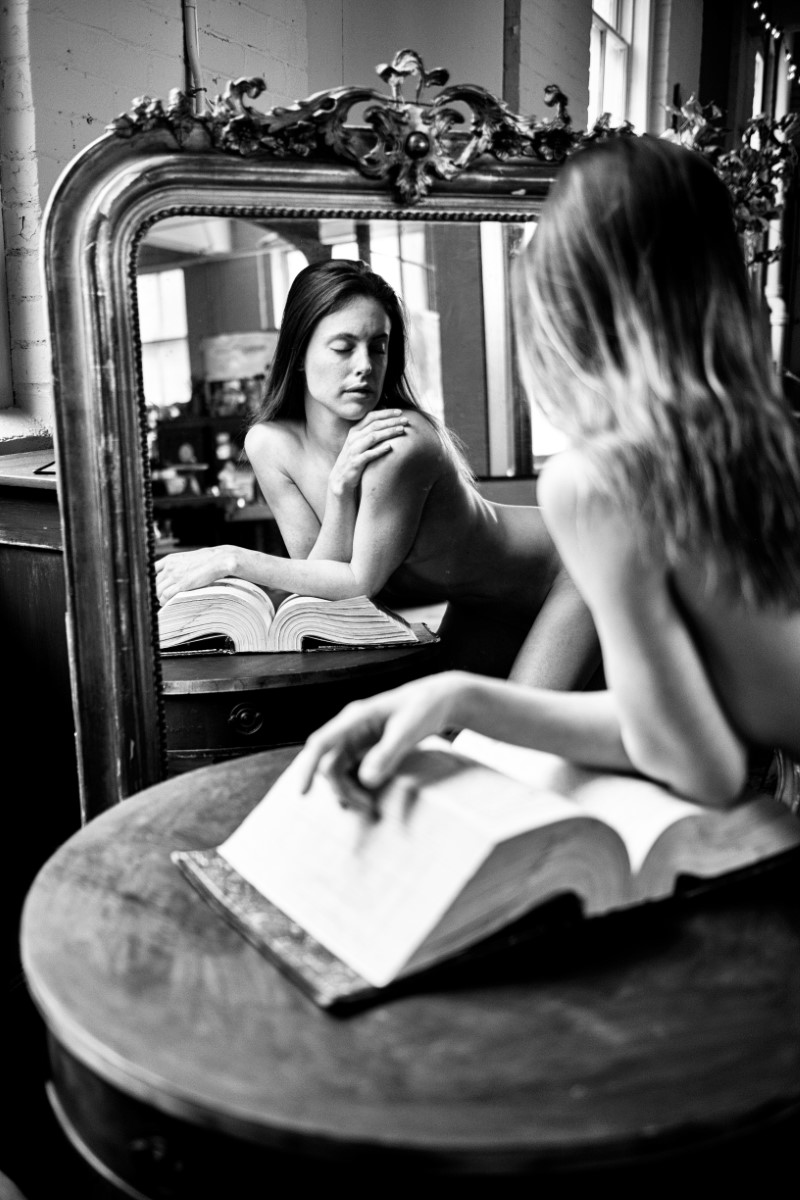

So, I am advocating a return to basics. I believe that the Body deserves better than the slavery of work, sex and war. The Body deserves to be put back on the pedestals from which we removed it back when religion took out its giant syringes and extracted pleasure and sacredness like two tumors out of one of the few remaining sacred places on Earth. Our shame in front of our mirrors made us slaves to those mirrors, to the perpetual need to prove ourselves. Mirrors should be philosophical instruments, not surgical devices.

Maybe the silence inherent in photographs will find its way back to us and remind us that stillness is as necessary as movement and as essential to the understanding of who we are. Speed, one of our century’s many drugs, does not facilitate understanding. We live in a world of fast moving mirrors. There is not enough time and courage to reflect ourselves in them. What we get is fragments that we fail to reassemble: the puzzle has too many pieces and we have also lost the instructions. Yet, for me, every click of the shutter release button is a contribution to somehow putting the puzzle back together. It’s a start. Perhaps we should start thinking about shattering all our mirrors and claim again our place in the world as sculptors with light.

Website: www.florinfirimita.com