When photography arrived in the United States in 1839, it landed first in a few east coast cities and New Orleans, and then spread north and west into the American interior. The proliferation of photography studios and photographers coincided with the beginnings of massive cultural, commercial, and transportation projects that would ultimately reshape much of the American landscape. Photography quickly became an accomplice in the transformation of the landscape, both passively and actively. Some photographs, for example, simply documented the changes in a landscape, often revealing the before and after of a construction project, while other photographs became agents of change, making visible sites that would become popular tourist destinations.

The New Orleans Museum of Art presents the exhibition East of the Mississippi: Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography from October 6, 2017–January 7, 2018. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, in association with NOMA, this landmark exhibition is the first to explore a vivid chapter of America’s photographic history—the origins of landscape photography in the United States.

This project is the first to articulate a complete history of landscape photography in the nineteenth-century American East, bringing together some of the rarest and most extraordinary photographs to tell the many stories of photography’s relationship to the landscape. Due to the rarity and fragility of these works, this is the first and perhaps only time that many of these objects will be publicly exhibited, offering visitors the rare opportunity to engage directly with objects from the origins of photography in this country.

There are roughly three different kinds of landscape that are presented in East of the Mississippi: the natural landscape, the built landscape, and the urban landscape. The following selection presents examples of each kind of landscape and several different kinds of photographic processes. It also provides some insight into the variety of reasons that photographers engaged with the eastern American landscape in the nineteenth-century.

East of the Mississippi

Nineteenth-Century American Landscape Photography

October 5, 2017 – January 7, 2018

New Orleans Museum of Art

1 Collins Diboll Circle New Orleans, LA 70124

noma.org

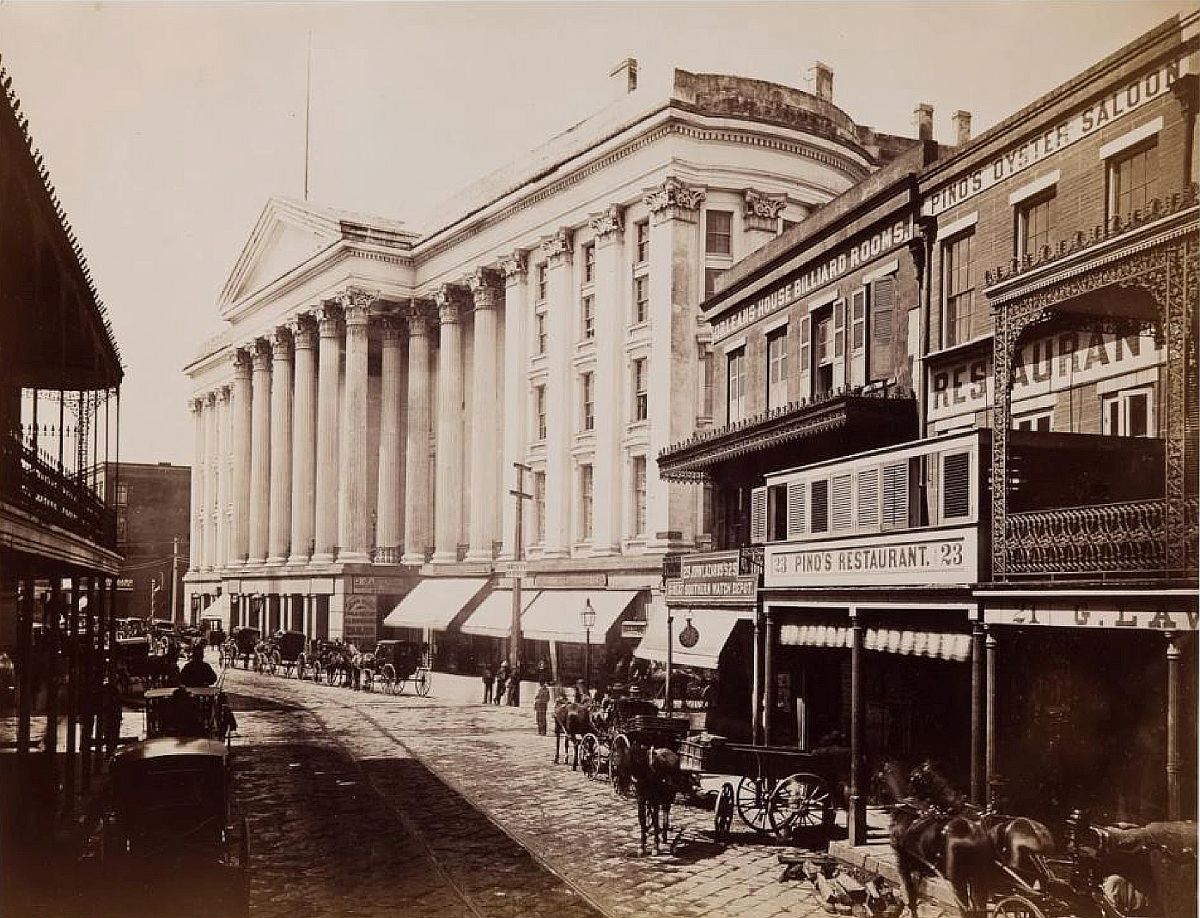

Theodore Lilienthal, St. Charles Hotel, New Orleans, 1867, albumen print, 10 3/4 x 13 13/16 in., New Orleans Museum of Art, Museum Purchase, 2013.21

In early 1867, Theodore Lilienthal was hired by the city council of New Orleans to produce a lavish presentation portfolio of large photographs of New Orleans that could be given as a gift to Napoleon III on the occasion of the International Exposition that year. The project was the first municipal photographic commission in the United States. This photograph was contact printed from a glass negative of equal size—the largest known to have been produced in New Orleans in the nineteenth century. The incredible detail that these large negatives afforded provides a great deal of information about this block of the city and even about the making of the picture: the giant pocket watch hanging down from John Lazarus’s Great Southern Watch Depot preserves the time that this picture was made, just a couple of minutes after ten o’clock in the morning.

Jay Dearborn Edwards, Esplanade Street from Royal Street toward Lake, 1858–1861, Salted paper print, 7 1/2 x 9 3/8 in., The Historic New Orleans Collection

Jay Dearborn Edwards had a nomadic and multi-faceted career that included travelling from New Hampshire to New Orleans, and stints as an itinerant phrenologist (studying the shape of heads as signs of moral character) and as a confederate spy. While in New Orleans, however, he became one of the earliest photographers to make paper photographs (daguerreotypes were much more common here). This image, of Esplanade at Royal Street presents a view down the avenue that today terminates at the steps of NOMA.

Edward Steichen, Woods Twilight, 1898, platinum print, 6 x 7 11/16 in., Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1933

At the end of the nineteenth century, the introduction of the Kodak camera forced a division amongst photographic picture makers. The most serious art photographers organized themselves into clubs and focused on laborious and often heavily hand manipulated printing processes to separate themselves from the fleets of casual photographers. The movement ultimately became known as the Pictorialist movement. Steichen’s ethereal representation of the woods near his hometown Milwaukee is a masterful example of how attention to every aspect of the production of a photograph could profoundly influence its effect. In the hands of another photographer, the wispy trees would be more substantially described, but Steichen is more interested in the feeling than the fact, and has created a picture that mirrors an experience of twilight instead of its actual appearance.

Henry Peter Bosse, Construction of Rock and Brush Dam, L.W., 1891, Cyanotype, 10 7/16 x 13 1/8 inches, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mary and Dan Solomon

Henry Peter Bosse was appointed draftsman and cartographer for the US Army Corps of Engineers and was charged with surveying the Mississippi River. He produced maps as well as photographs of the river and its surrounding area that documented both natural and man-made sites. This print is a cyanotype, an iron based photograph that is essentially the same compound used in blueprints. Since the photograph was produced for an engineering survey of water, the cyanotype, with its deep blue color, was a doubly appropriate print choice. Bosse suffered an early and sudden death after eating spoiled canned asparagus.

John Moran, The Wissahickon Creek near Philadelphia, c. 1863, Albumen print, 10 3/8 x 13 inches, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation through Robert and Joyce Menschel

John Moran spent much of his career trying to advance the notion of photography as a fine art in the United States. This photograph conforms to an historic mode of landscape representation, the picturesque, whose origins reside in European drawing and painting traditions. Perhaps most importantly, seated on a stool in the foreground is an artist, the photographer’s brother, Thomas Moran, sketching the landscape. While the artist gazing upon nature is a trope in landscape painting, here in the photograph it takes on the tone of an argument: this photograph is both about art, and is art itself.

Hugh Lee Pattinson, American Falls, 1840, daguerreotype, 6 1/2 x 8 1/2 in., Robinson Library, Newcastle University, England

This daguerreotype is one of several that Hugh Lee Pattinson, a British chemical metallurgist, made in April of 1840 while visiting the United States. Together, Pattinson’s daguerreotypes are the oldest known photographs of Canada, but they are amongst the oldest known photographs made in the U.S. The daguerreotype process involved coating a copper plate with a chemical solution that produced an image when exposed to light. Each one is unique; a daguerreotype is a negative and positive in one, and cannot serve as a matrix to produce multiple positive prints. Nevertheless, daguerreotypes were frequently copied as engravings and reproduced in printer’s ink. One of Pattinson’s daguerreotypes of Niagara Falls was reproduced in this manner and included in the first publication to be based on photographic images, a two volume publication called Excursions daguerriennes.