Eadweard Muybridge (1830 – 1904) was an English photographer important for his pioneering work in photographic studies of motion, and early work in motion-picture projection. He adopted the first name Eadweard as the original Anglo-Saxon form of Edward, and the surname Muybridge believing it to be similarly archaic.

Muybridge emigrated to the United States at the age of 20, arriving in New York City and later moving to San Francisco in 1855, a few years after California became a state, and while the city was still the “capital of the Gold Rush”. He started a career as a publisher’s agent for the London Printing and Publishing Company, and as a bookseller. At the time, the city was booming, with 40 bookstores, nearly 60 hotels and a dozen photography studios. Later in his life, he wrote about also having spent time in New Orleans and New York City during his early years in the United States.

In central Texas, Muybridge suffered severe head injuries in a violent runaway stagecoach crash which injured every passenger on board, and killed one of them. Muybridge was bodily ejected from the vehicle, and hit his head on a rock or other hard object. He was taken 150 miles (240 km) to Fort Smith, Arkansas, for treatment (his earliest memories post-accident were there), where he stayed three months, trying to recover from symptoms of double vision, confused thinking, impaired sense of taste and smell, and other problems. He next went to New York City, where he continued in treatment for nearly a year before being able to sail to England.

Arthur P. Shimamura, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has speculated that Muybridge suffered substantial injuries to the orbitofrontal cortex that probably also extended into the anterior temporal lobes, which may have led to some of the emotional, eccentric behavior reported by friends in later years, as well as freeing his creativity from conventional social inhibitions. Today, there still is little effective treatment for this kind of injury.

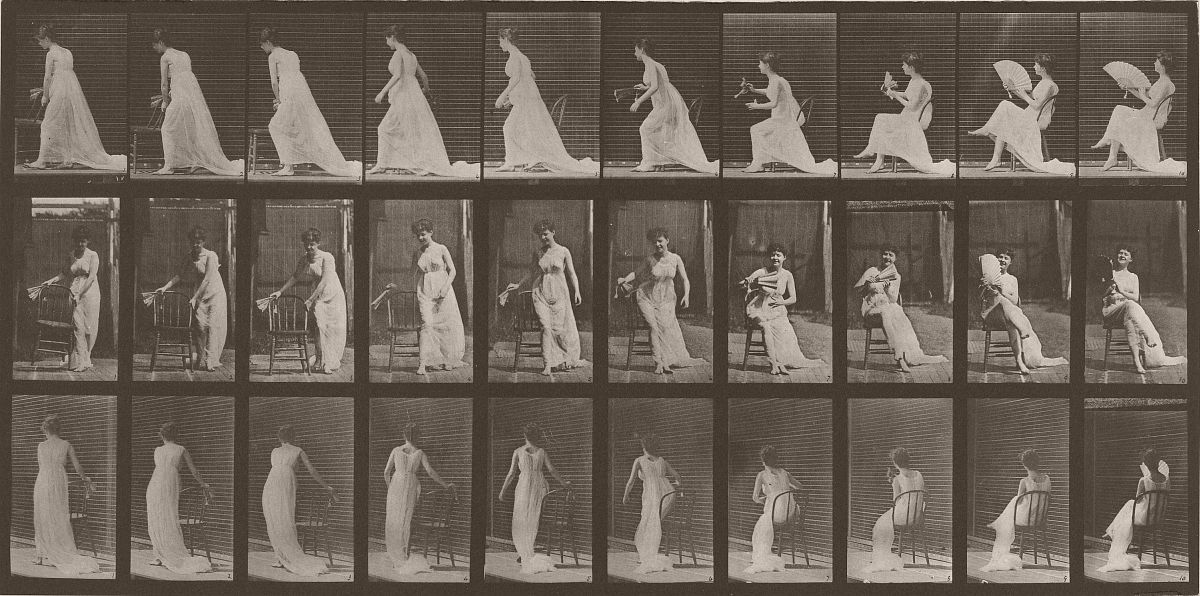

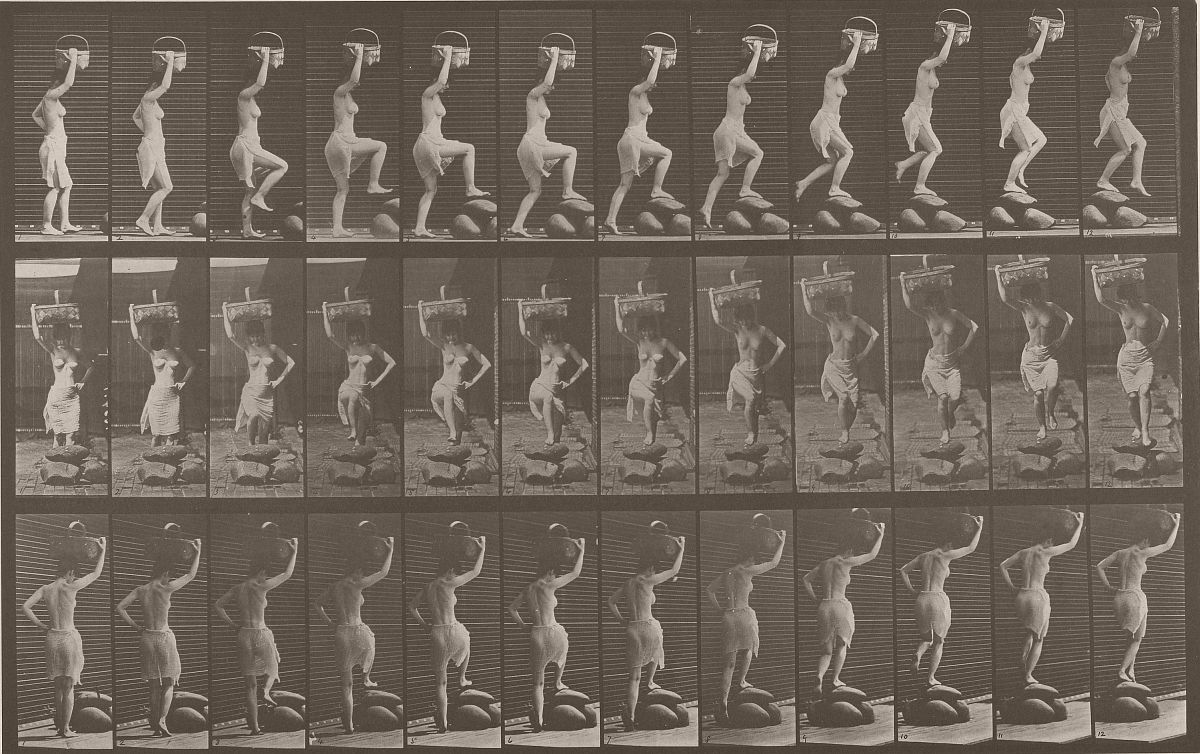

While recuperating in England and receiving treatment from Sir William Gull, Muybridge took up the new field of professional photography sometime between 1861 and 1866. Muybridge later stated that he had changed his vocation at the suggestion of his physician. He learned the wet-plate collodion process in England, and may have been influenced by some of the great English photographers of those years, such as Julia Margaret Cameron. Also during this period, Muybridge secured at least two British patents for his inventions, including the design of a high speed electrical shutter and electro-timer, to be used alongside a battery of up to 24 cameras.

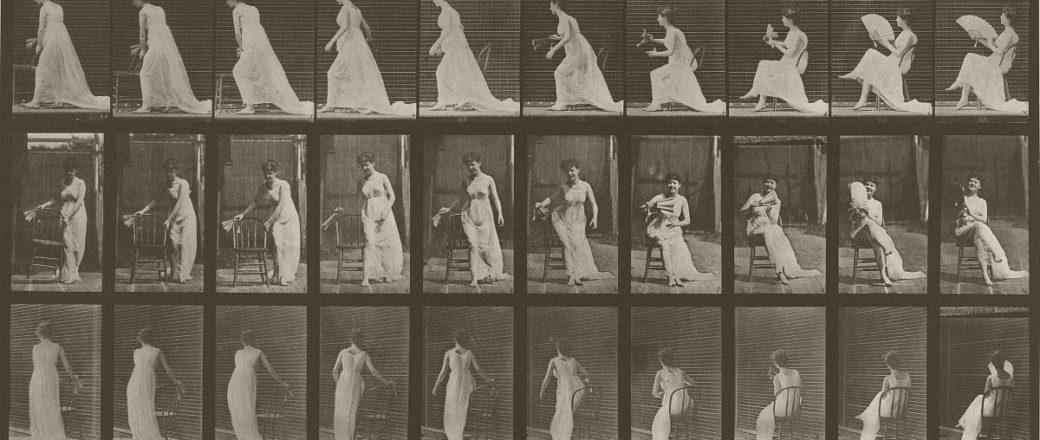

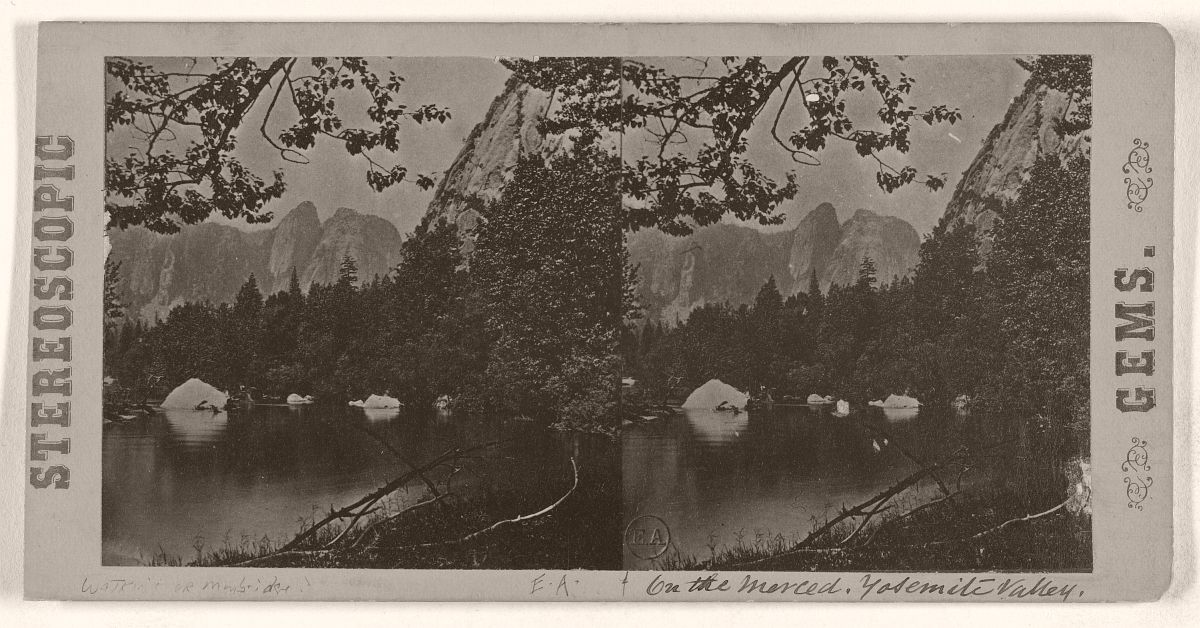

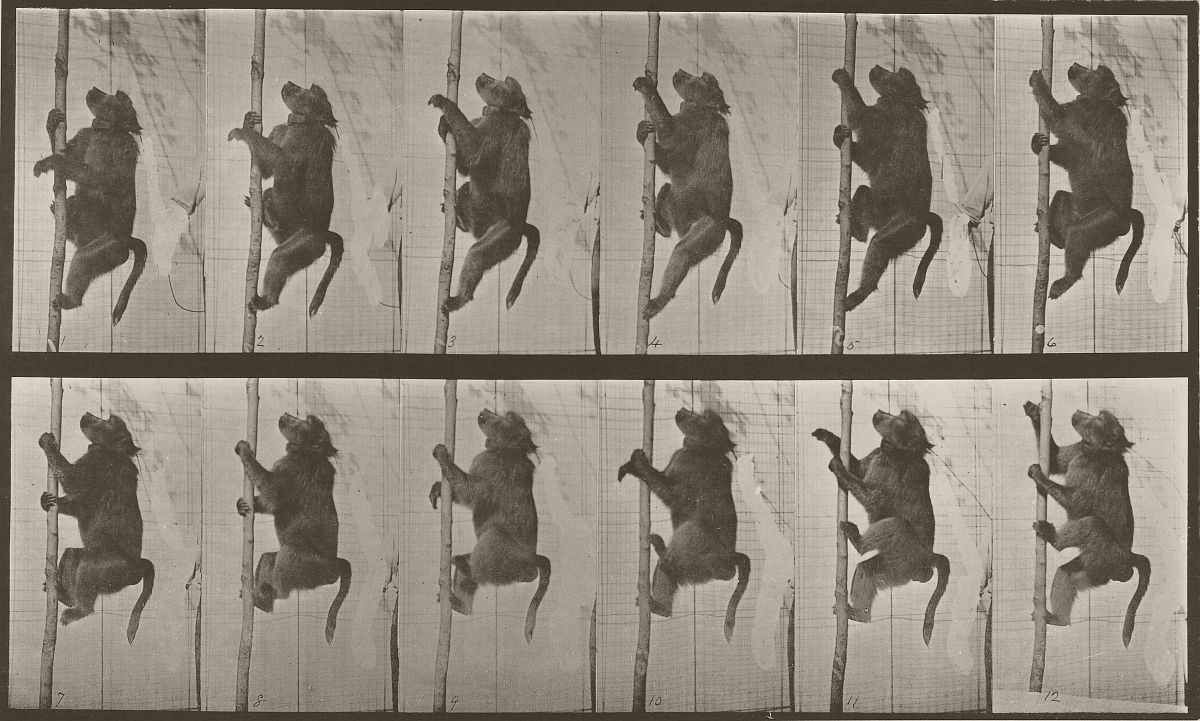

Muybridge had left San Francisco in 1860 as a merchant, but returned in 1867 as a professional photographer, with highly proficient technical skills and an artist’s eye. He became successful in photography, focusing principally on landscape and architectural subjects. He converted a lightweight carriage into a portable darkroom to carry out his work. His business cards also advertised his services for portraiture. His stereographs, the popular format of the time, were sold by various galleries and photographic entrepreneurs (most notably the firm of Bradley & Rulofson) on Montgomery Street, San Francisco. Early in his new career, Muybridge was hired by Robert B. Woodward (1824–1879) to take extensive photos of his Woodward’s Gardens, a combination amusement park, zoo, museum, and aquarium which opened in San Francisco in 1866.

Muybridge established his reputation in 1867, with photos of the Yosemite Valley wilderness (some of which used the same scenes taken by his contemporary Carleton Watkins) and areas around San Francisco. Muybridge gained notice for his landscape photographs, which showed the grandeur and expansiveness of the West; if human figures were portrayed, they were dwarfed by their surroundings, as in Chinese landscape paintings. He signed and published his work under the pseudonym Helios, which he also used as the name of his studio.

Muybridge took enormous physical risks to make his photographs, using a heavy view camera and stacks of glass plate negatives. A spectacular stereograph he published in 1872 shows him sitting casually on a projecting rock over the Yosemite Valley, with 2,000 feet (610 m) of empty space yawning below him.

In 1868, Muybridge travelled to the newly acquired US territory of Alaska to photograph the Tlingit Native Americans, occasional Russian inhabitants, and dramatic landscapes for the US government. In 1871, the Lighthouse Board hired Muybridge to photograph lighthouses of the American west coast. From March to July, he travelled aboard the Lighthouse Tender Shubrick to document these structures. In 1873, Muybridge was commissioned by the US Army to photograph the Modoc War against the Native Americans in northern California and Oregon. Many of his stereoscopic photos were published widely, and can still be found today.

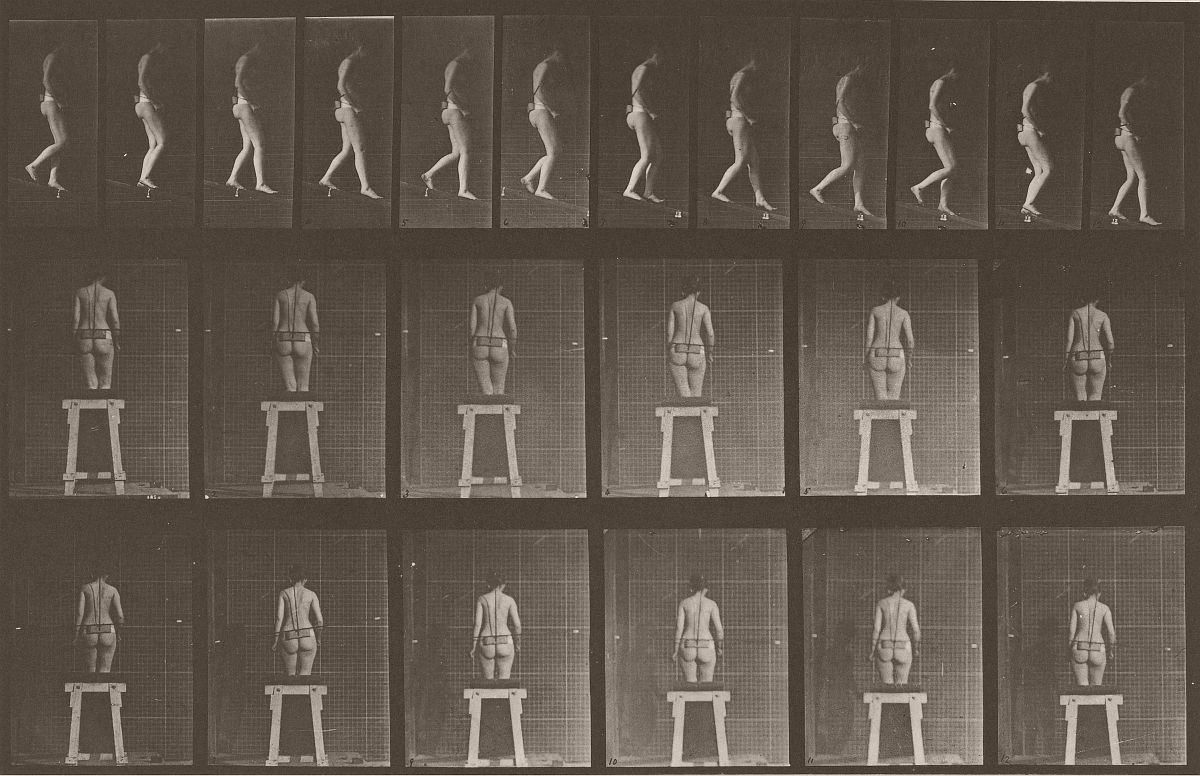

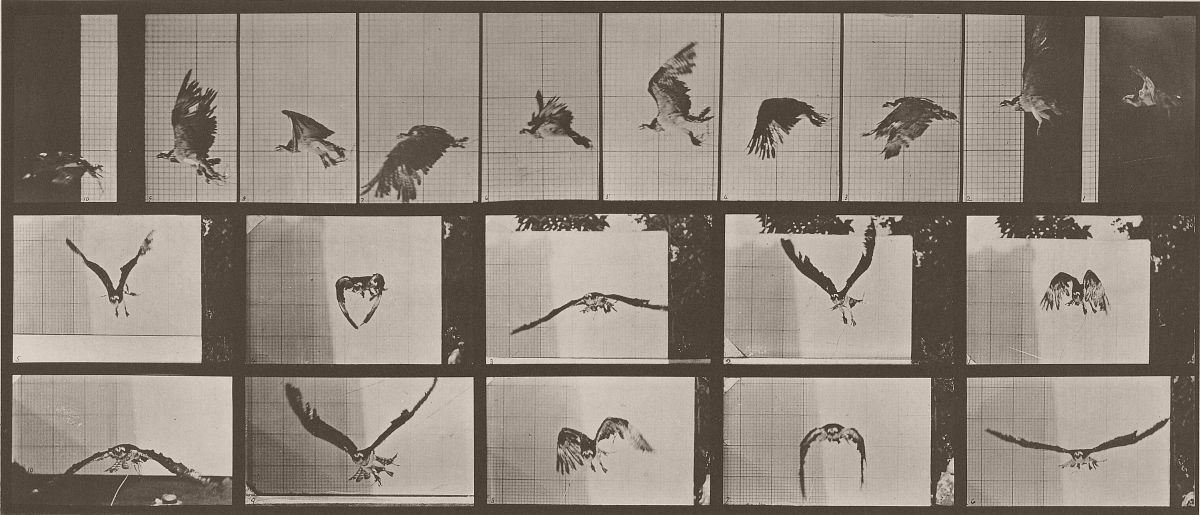

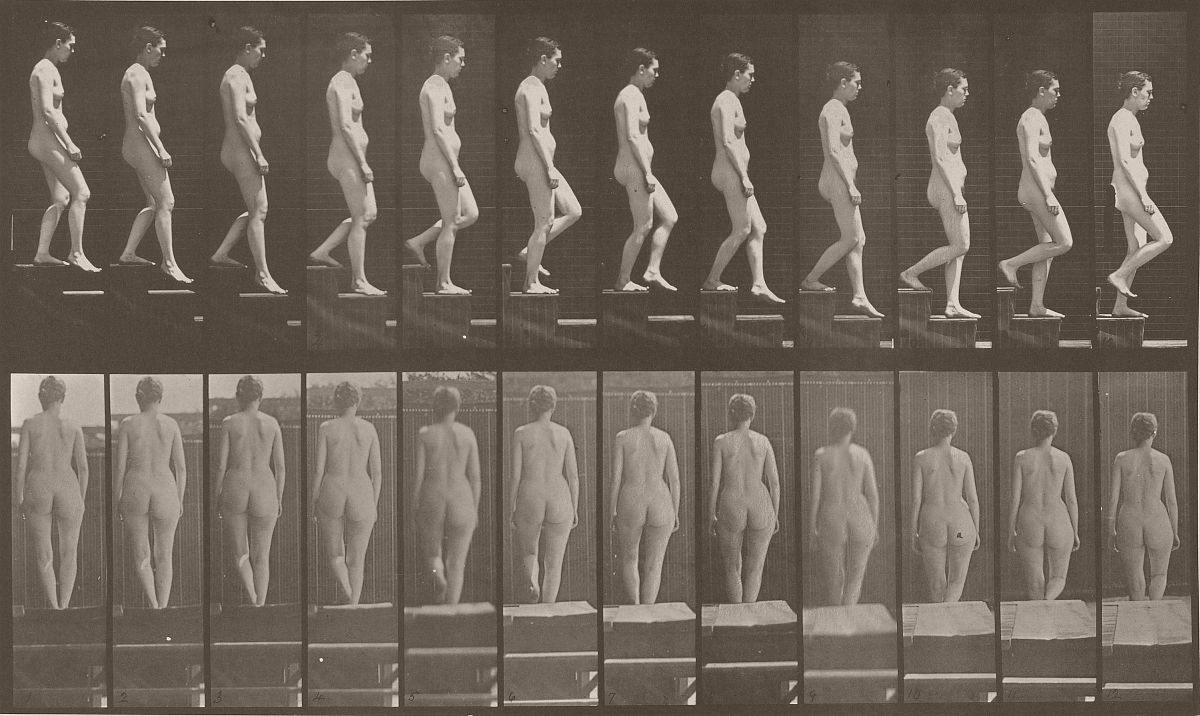

In 1872, the former governor of California, Leland Stanford, a businessman and race-horse owner, hired Muybridge for some photographic studies. He had taken a position on a popularly debated question of the day — whether all four feet of a horse were off the ground at the same time while trotting. In 1872, Muybridge began experimenting with an array of 12 cameras photographing a galloping horse in a sequence of shots. His initial efforts seemed to prove that Stanford was right, but he didn’t have the process perfected. The same question had arisen about the actions of horses during a gallop. The human eye could not break down the action at the quick gaits of the trot and gallop. Up until this time, most artists painted horses at a trot with one foot always on the ground; and at a full gallop with the front legs extended forward and the hind legs extended to the rear, and all feet off the ground. Stanford sided with the assertion of “unsupported transit” in the trot and gallop, and decided to have it proven scientifically. Stanford sought out Muybridge and hired him to settle the question.

Between 1878 and 1884, Muybridge perfected his method of horses in motion, proving that they do have all four hooves off the ground during their running stride. In 1872, Muybridge settled Stanford’s question with a single photographic negative showing his Standardbred trotting horse named Occident, airborne at the trot. This negative was lost, but the image survives through woodcuts made at the time (the technology for printed reproductions of photographs was still being developed). He later did additional studies, as well as improving his camera for quicker shutter speed and faster film emulsions. By 1878, spurred on by Stanford to expand the experiments, Muybridge had successfully photographed a horse at a trot; lantern slides have survived of this later work. Scientific American was among the publications at the time that carried reports of Muybridge’s ground-breaking images.

Stanford also wanted a study of the horse at a gallop. Muybridge planned to take a series of photographs on 15 June 1878, at Stanford’s Palo Alto Stock Farm (now the campus of Stanford University). He placed numerous large glass-plate cameras in a line along the edge of the track; the shutter of each was triggered by a thread as the horse passed (in later studies he used a clockwork device to set off the shutters and capture the images). The path was lined with cloth sheets to reflect as much light as possible. He copied the images in the form of silhouettes onto a disc to be viewed in a machine he had invented, which he called a “zoopraxiscope”. This device was later regarded as an early movie projector, and the process as an intermediate stage toward motion pictures or cinematography.

The study is called Sallie Gardner at a Gallop or The Horse in Motion; it shows images of the horse with all feet off the ground. This did not take place when the horse’s legs were extended to the front and back, as imagined by contemporary illustrators, but when its legs were collected beneath its body as it switched from “pulling” with the front legs to “pushing” with the back legs.