The Münchner Stadtmuseum is holding the first-ever retrospective of French photographer Adolphe Braun (1812-1877) to be hosted by a German-speaking country. The exhibition draws on the Museum’s own extensive collection complemented by loans from around the world, and presents some 400 original Braun photographs, along with some 20 paintings by a number of international artists.

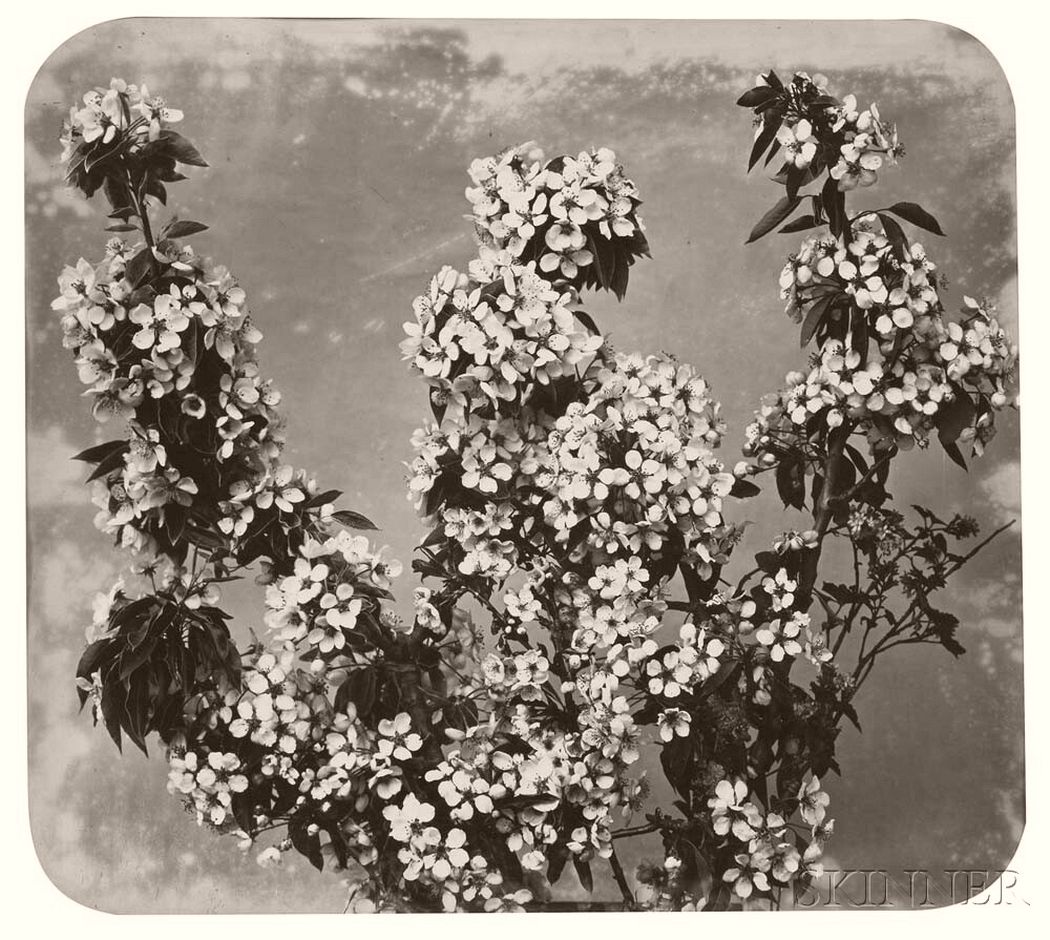

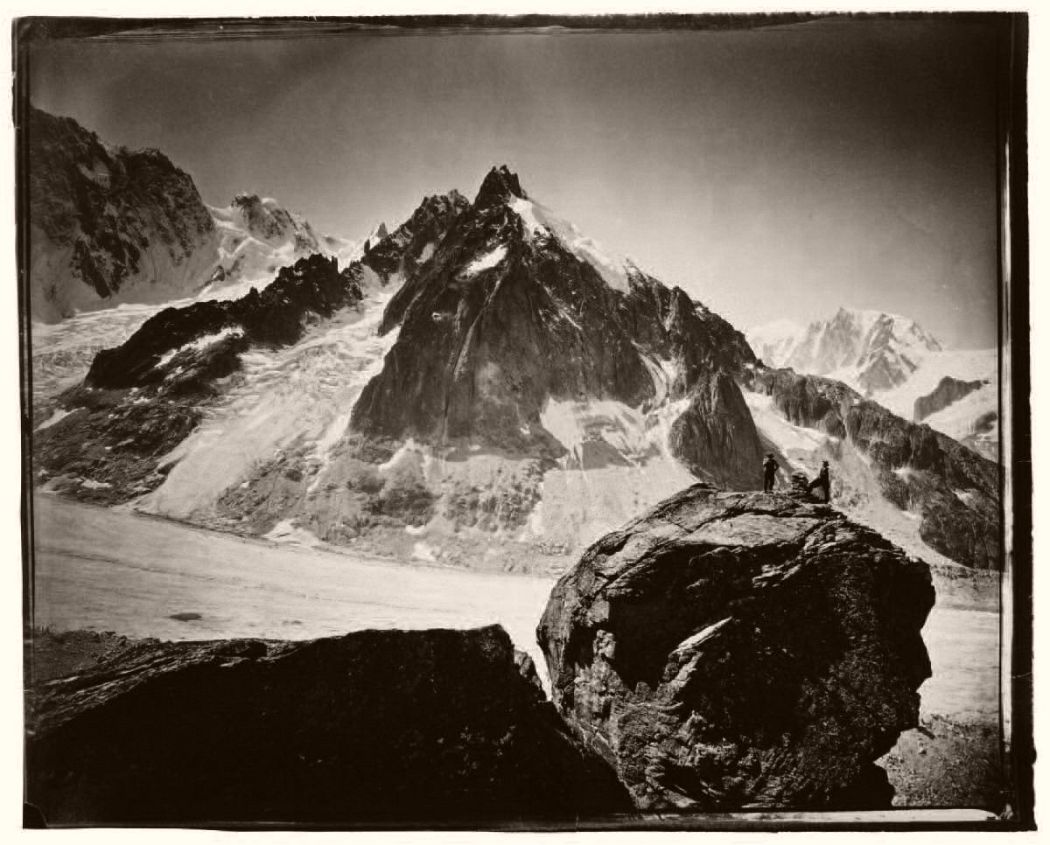

Adolphe Braun was one of the most prominent and influential photographers in 19th century Europe. In 1855, the erstwhile textile designer made his debut as a photographer at the Paris Universal Exposition with a series of floral studies. International visitors were so captivated by the beauty of the familiar still life captured through the medium of photography that not only did the images prove popular as models for artisans but they also caused a stir in the art world. Braun would subsequently prove to be a great experimenter behind the camera. With the support of a few family members and a handful of employees, he founded “Ad. Braun et Cie.”, a photography business, and together they pioneered Alpine photography. Perilous expeditions in the high mountains produced large-format landscapes of the Swiss Alps that appealed to the scientific community and tourists alike. These images document a natural landscape undergoing rapid change as a result of industrialization and a changing climate. To this day, they remain some of the most striking pictures ever taken of Alpine scenery.

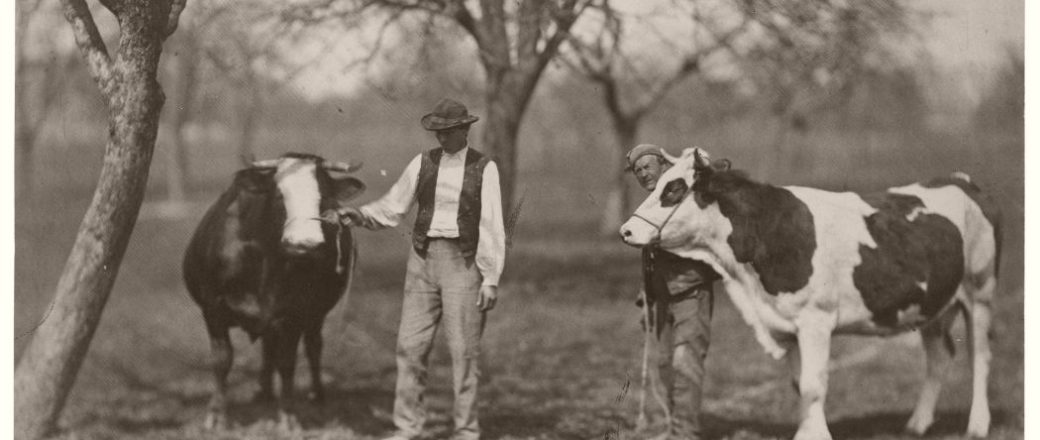

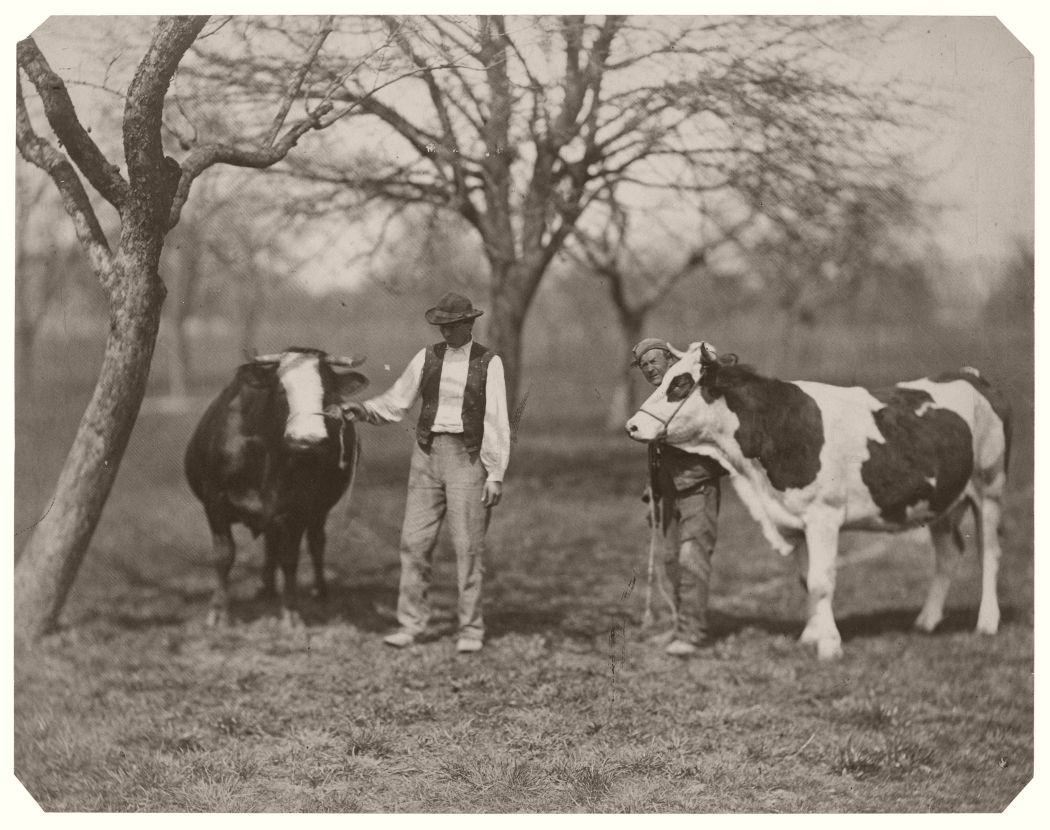

Braun’s photographs made a huge impression on French painter, Gustave Courbet, and were the inspiration for “Château Chillon”, which depicts the eponymous Swiss castle on the shores of Lake Geneva. In the exhibition, this painting takes center stage alongside works by Alexandre Calame displayed next to the photographs on which they were based. The exhibition devotes twelve chapters to the ways in which Adolphe Braun’s imagery influenced the visual arts in the 19th century. Braun discovered that a soft-focus effect could lend a painting-like quality to his photographic portraits – not portraits of people, but of horses, sheep and cows. Painters including Rosa Bonheur and Albert Heinrich Brendel used these animal images as models for their paintings. The dead animal as a memento mori, a well-established artistic motif ever since the early modern period, became the subject of a series of large-format still-life hunting images. American artist William Harnett, who would later go on to revolutionize American still-life painting, encountered these on a visit to Munich. Braun’s photographs of Egypt also provided a fresh source of inspiration for the Orientalism that was in vogue in the 19th century. While this series was shot for the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, it did not adopt a photo documentary style. These Egyptian photographs depict picturesque scenes of the Nile’s distinctive natural environment and were used by artists such as painter Eugène Fromentin as additional resources.

Alsatian painter, Jean-Jacques Henner, was a close friend of Adolphe Braun’s son, Gaston. Both this artist and the photography business shared a mutual interest in Alsatian and Swiss folklore, and this fascination found expression in numerous genre scenes and costume studies. The black-and-white photographs they jointly produced were laboriously hand-colored to ensure they lost nothing in comparison with paintings. Yet the results were more kitsch than art, and the market for photographs of this nature remained confined to the Alsace region. Nevertheless, Braun’s images did serve as a source for the paintings of Jean-Jacques Henner. Meanwhile, reproductions of works of art and drawings from Europe’s foremost museums and private collections started to become particularly important to artists. The company, even before 1885 when it became the official photographer of the Louvre, had already produced more than 30,000 prints, mostly of Italian, Dutch and French art, reflecting the tastes of the time. In 1869, for instance, the company’s photographers documented Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, sparking an interest in photography not only among artists but also among art historians. The opportunity to examine photographs of works of art had a significant influence on the emerging discipline of art history, and several prominent art historians of the day worked closely with Adolphe Braun’s company.

At the very time when reproduction work was really starting to take off, the Franco-Prussian War laid waste to towns, cities and large areas of countryside in France. In 1871, Braun took a series of photographs of Paris and Belfort, both to document the devastation caused by the war and because good money could be made from pictures of the destruction. One photograph mirrors Ernest Meissonier’s iconic Paris Commune painting “The Ruins of the Tuileries Palace”. Braun also lamented the loss of Alsace and Lorraine to Germany after France’s defeat in the war through his allegorical depictions of two young women wearing each region’s traditional dress. These powerfully symbolic images proved extremely popular as prints, in the printed media and also on postcards, chinaware and textiles.

A comprehensive catalog with contributions by Ulrich Pohlmann and Paul Mellenthin (eds.) and Jan von Brevern, Christian Kempf, Dorothea Peters, Marie Robert, Aziza Gril-Mariotte and Bernd Stiegler will be published by Schirmer / Mosel Verlag. 340 pages.

The exhibition is a collaboration with the Musée Unterlinden in Colmar which will subsequently host the exhibition in spring 2018.

Adolphe Braun

A European Photography Business and the 19th-Century Visual Arts

6 Oct 2017 – 21 Jan 2018

Münchner Stadtmuseum

St.-Jakobs-Platz 1

80331 München

www.muenchner-stadtmuseum.de