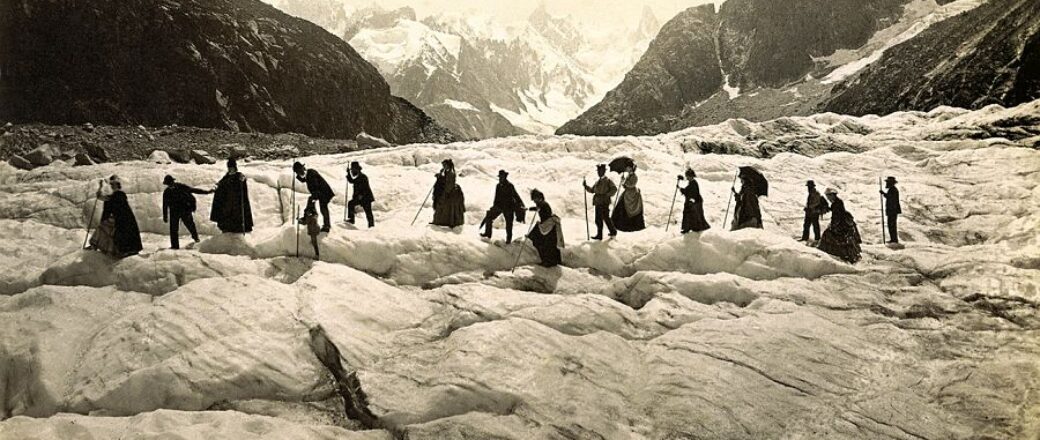

Photography, born in the 19th century, accompanied the discovery of the mountains. The year following its invention, the first photographers set up their darkrooms in the middle of the Alpine landscape. Most of them were enlightened amateurs, passionate about the new medium, which offered images of extraordinary precision. To record and fix the image from the action of light, a good knowledge of chemistry and physics was required. The first photographic process, developed in 1839 and called the daguerreotype, dominated the market until 1850. Requiring long exposure times and producing a single image, the daguerreotype is a photograph on a thin copper plate coated with silver. Although only a handful of daguerreotypes of the Alps were produced in the 1840s, mostly at medium altitudes, and even fewer survive, some images were reproduced in albums as engravings and lithographs. Throughout the 19th century, photographers made numerous technical improvements to the process, notably moving from the single metal plate of the daguerreotype to the negative, which allowed images to be produced on paper in large quantities.

The various stages of development were also gradually simplified, and exposure times reduced. The metal plates were replaced by glass plates, covered with a layer of photographic emulsion, and then developed in a chemical bath. With the invention of the negative-positive process, photography became reproducible: the image produced on the glass plate was then printed on photosensitive paper, known as albumen.

From the mid-19th century onwards, it was possible to produce unlimited numbers of prints. This led to a boom in the photographic market and publishers specialised in photographic views, distributing their images in albums which they sold to sold to a curious public at home and abroad. Faster and cheaper than in its early days, photography became accessible to the greatest number of people and was eventually taken on all journeys.

As the profession of photography developed in the 1850s, particularly as a result of the craze for photographic portraiture, many amateurs with the means to buy equipment learned to master the new medium. Among the first photographers were artists who saw it as a quick and efficient way to develop images, but also doctors, engineers and pharmacists with a penchant for science who were fascinated by the medium. From the late 1840s onwards, photographic equipment was taken on excursions: mountaineers in particular saw it as a way of sharing their passion for the mountains. As for professional photographers, they were integrated into the scientific missions of discovery of new territories, and brought back to the public unpublished images of the exploration of the high peaks. It isn’t barely an exaggeration to say that the Alps were invaded by photographers in the decades following the invention of the process.

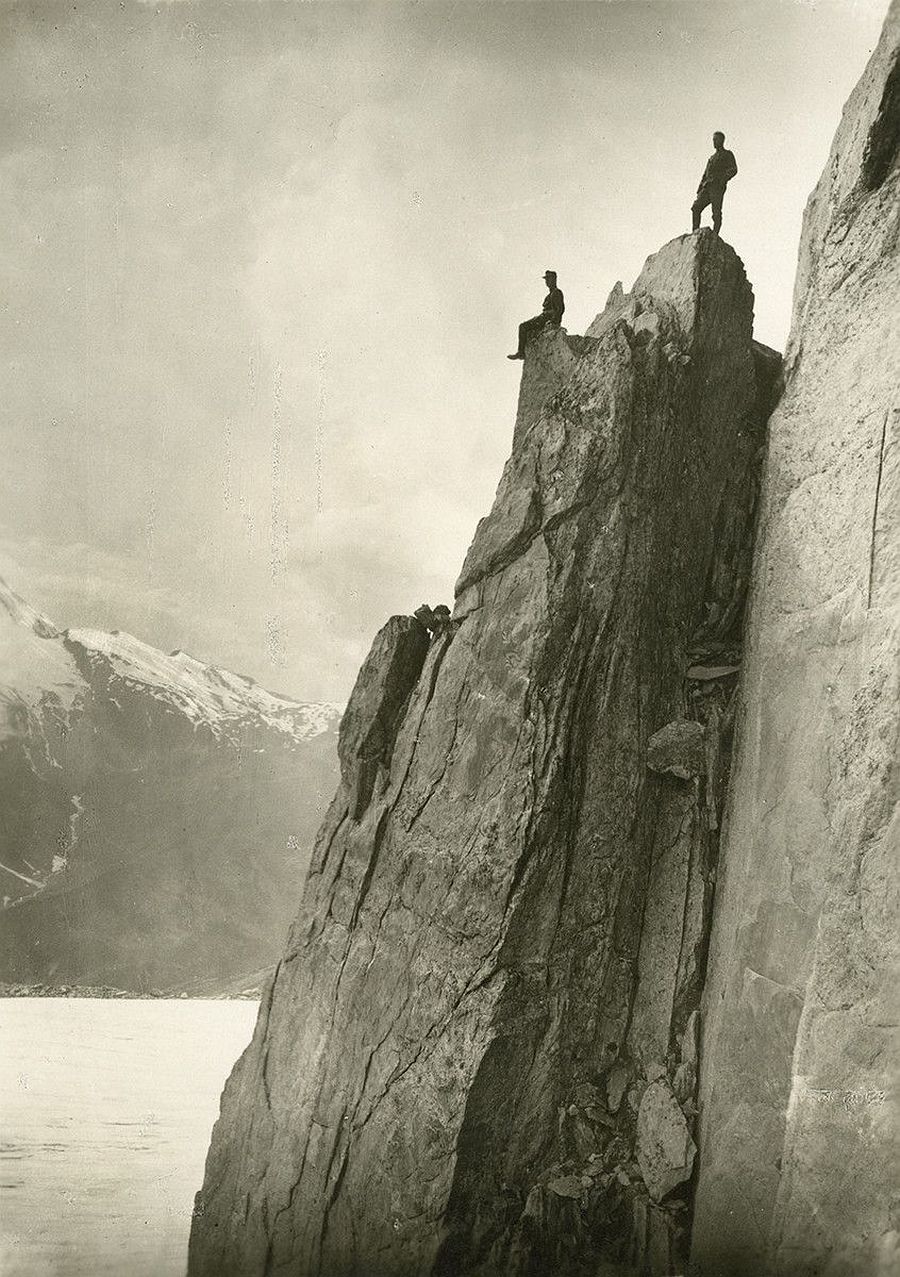

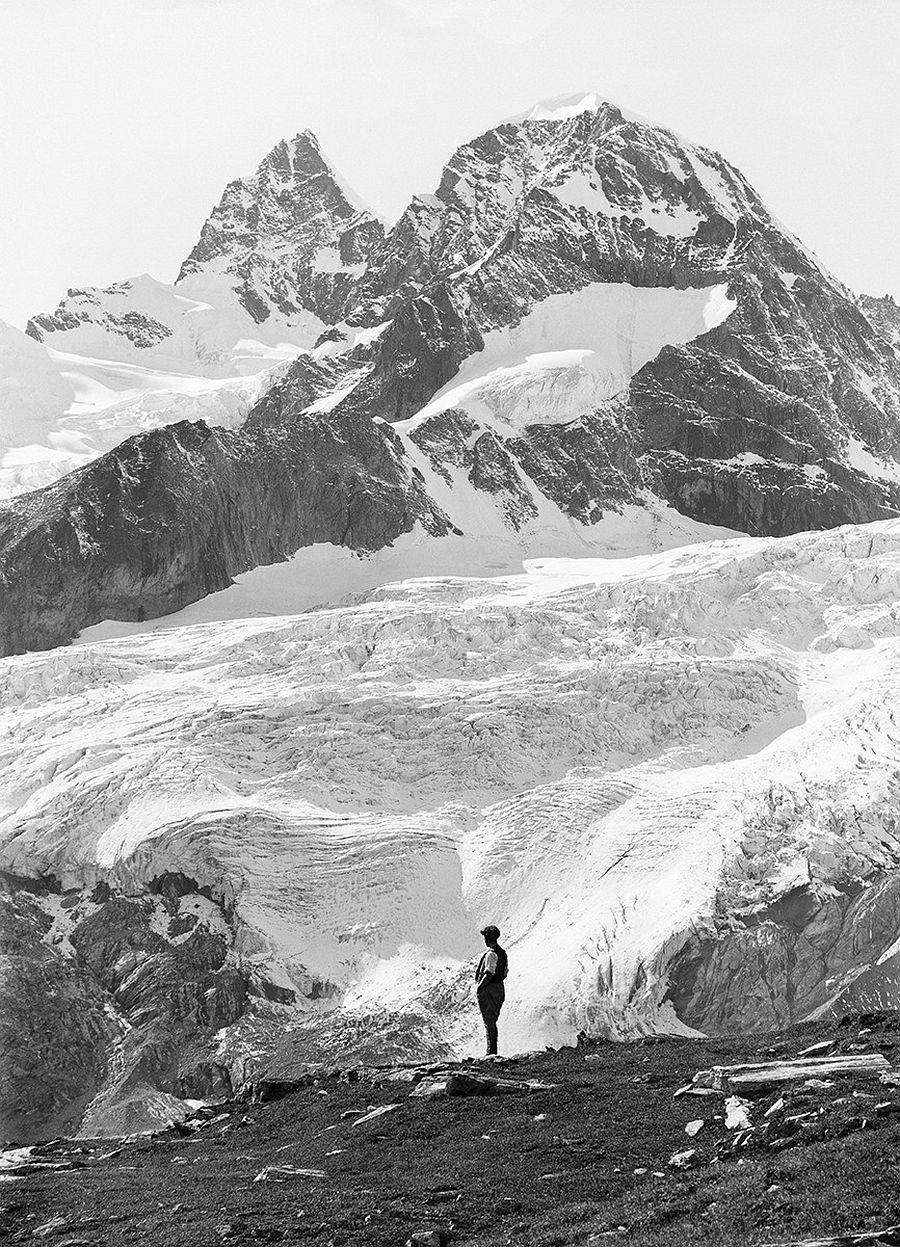

Although they struggled with difficult conditions, working with cumbersome equipment that in the early years required them to carry chemicals, glass plates and darkroom tents along cliffs, photographers managed to produce extraordinary images, offering a variety of viewpoints, sometimes offering panoramic views, sometimes focusing on seracs, glacial caves, gorges and waterfalls. But not all the photographers set out to conquer the high peaks. Some stayed at mid-altitude and photographed the mountain people, their habitats and their way of life. Geologists photographed rock formations and ice seas, beginning to document glacial movements scientifically, while civil engineers were interested in the infrastructure that opened up new routes through the mountains, such as the railway.

The exhibition shows the enthusiasm of the first generations of photographers for mountain landscapes in particular. Corresponding to the first 100 years of the history of photography, the period 1840-1940 shows the fundamental change in attitude towards the high peaks: this wild and dangerous space is suddenly perceived as a place of glorious nature and great beauty. The air is pure compared to the dark and unhealthy environment that develops in the cities. People went to the mountains for treatment and to distance themselves from the hustle and bustle of the city. Sanatoriums were founded in Switzerland at the end of the 19th century. Altitude cures were prescribed to patients who were recommended to engage in outdoor activities and to expose themselves to the sun. Thus, the mountains were symbolically associated with the health of the body, which in turn was associated with spiritual health. This period also coincides with the golden age of mountaineering, when all the great peaks were climbed. Explorations were adventurous not only in the Alps, which in the 19th century were still a territory to be discovered, but also on all other continents, from Africa to the Arctic, from New Zealand to the Andes, from Alaska to Tibet.

Montagne Magique Mystique

Treasures of Photography from Swiss Collections

8 May – 26 September 2021

MBAL Musée des beaux-arts

Marie-Anne-Calame 6

2400 Le Locle

www.mbal.ch

Auguste Garcin, Traversée de la mer de glace, Chamonix, vers 1865, épreuve albuminée. © Collection Crispini, Genève

Georges Tairraz II: Traversée de l’aiguille du Midi à l’aiguille du Plan, Massif du Mont-Blanc, 1932 épreuve au gélatino-bromure d’argent © Collection Crispini, Genève

Albert Nyfeler: Transport du bois pour la construction du chalet de Hans Lehner, Lauchernalp, 1936 © Albert Nyfeler, Médiathèque Valais – Martigny