Spencer Digby (1901 – 1995) was a New Zealand photographer. He ran a well-known and prestigious Wellington studio from 1936 to 1960. Ron Woolf purchased the business in 1960 and later gifted all the approximately 40,000 negatives to Te Papa.

After leaving school he worked for a time as a clerk with the meat company Vestey’s. He then became an assistant at R. N. Speaight’s photographic studios in Bond Street, London, whose clientele included members of England’s nobility.

Fearing he would never rise far working for Speaight, Digby was advised by a New Zealand woman to contact the photographic firm S. P. Andrew Limited in Auckland. After an exchange of letters he received a job offer, which he accepted, arriving in Auckland around 1923. He later spent some time working at the firm’s branch in Wellington, where he met Edna Theresa Plimmer, the daughter of well-known journalist W. H. Plimmer. They were married in Wellington on 24 April 1930, and were to have two daughters.

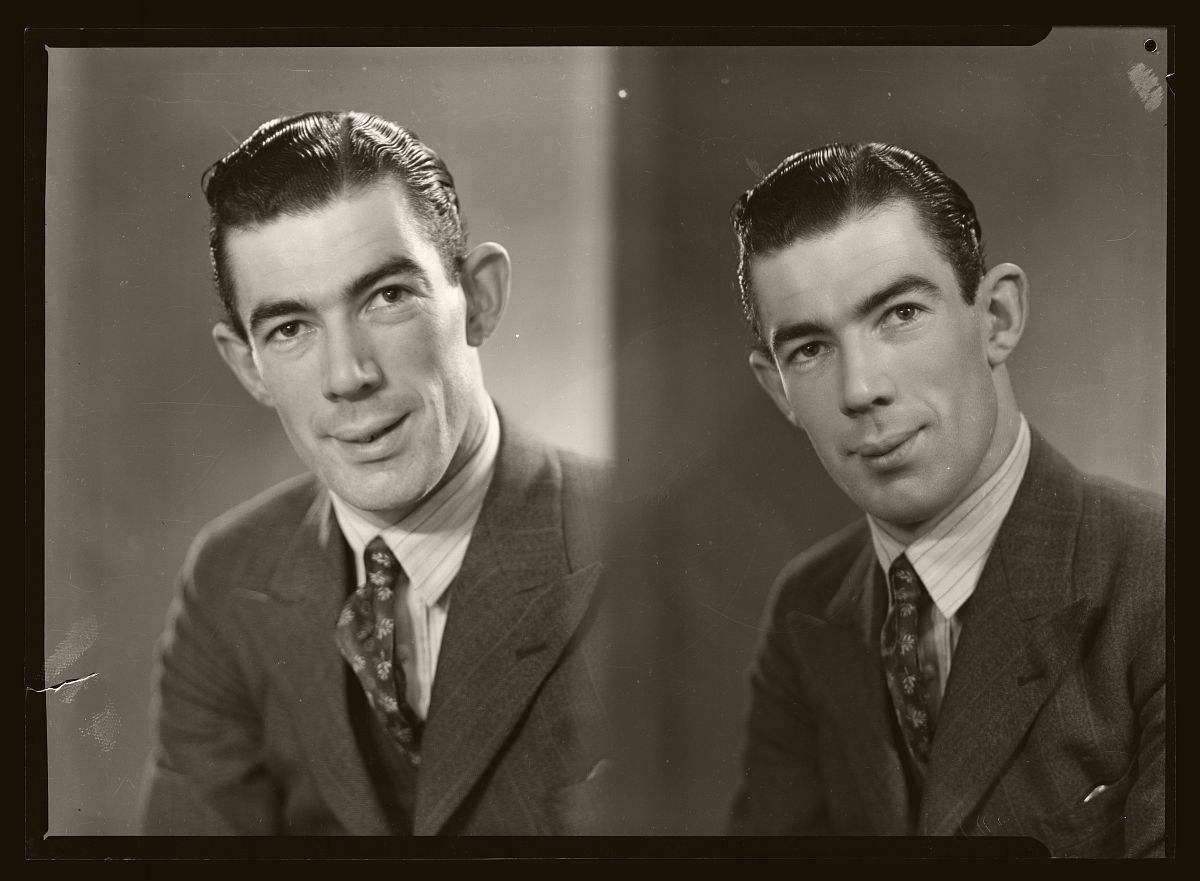

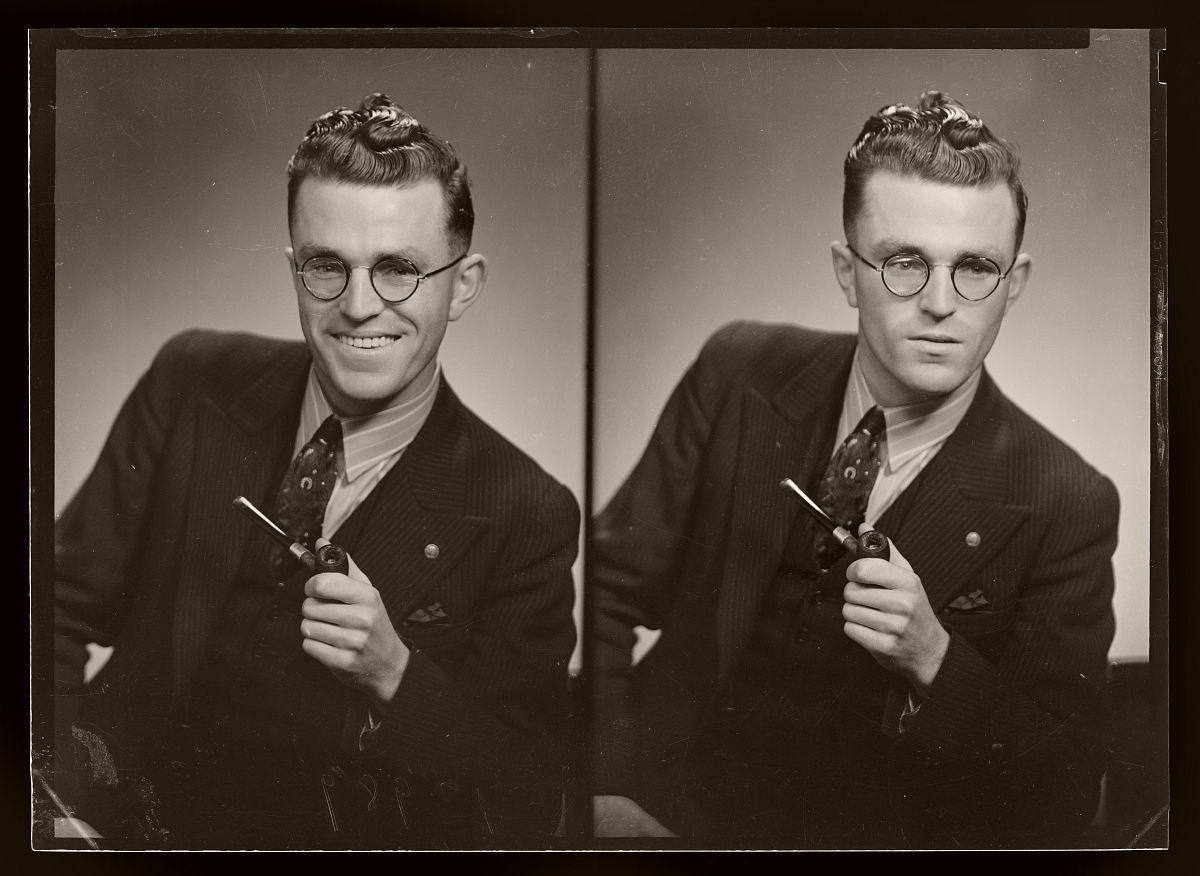

Two years later Digby decided to branch out on his own. In 1934 he moved into a specially designed studio in the new Prudential Assurance Company building on Lambton Quay, and quickly established himself as one of the capital’s leading society photographers. His work from this period was noted for its subtle use of photo-flood and spotlighting in modelling the features of the sitter, skills he subsequently passed on to Brian Brake, who worked for him from 1945 to 1949.

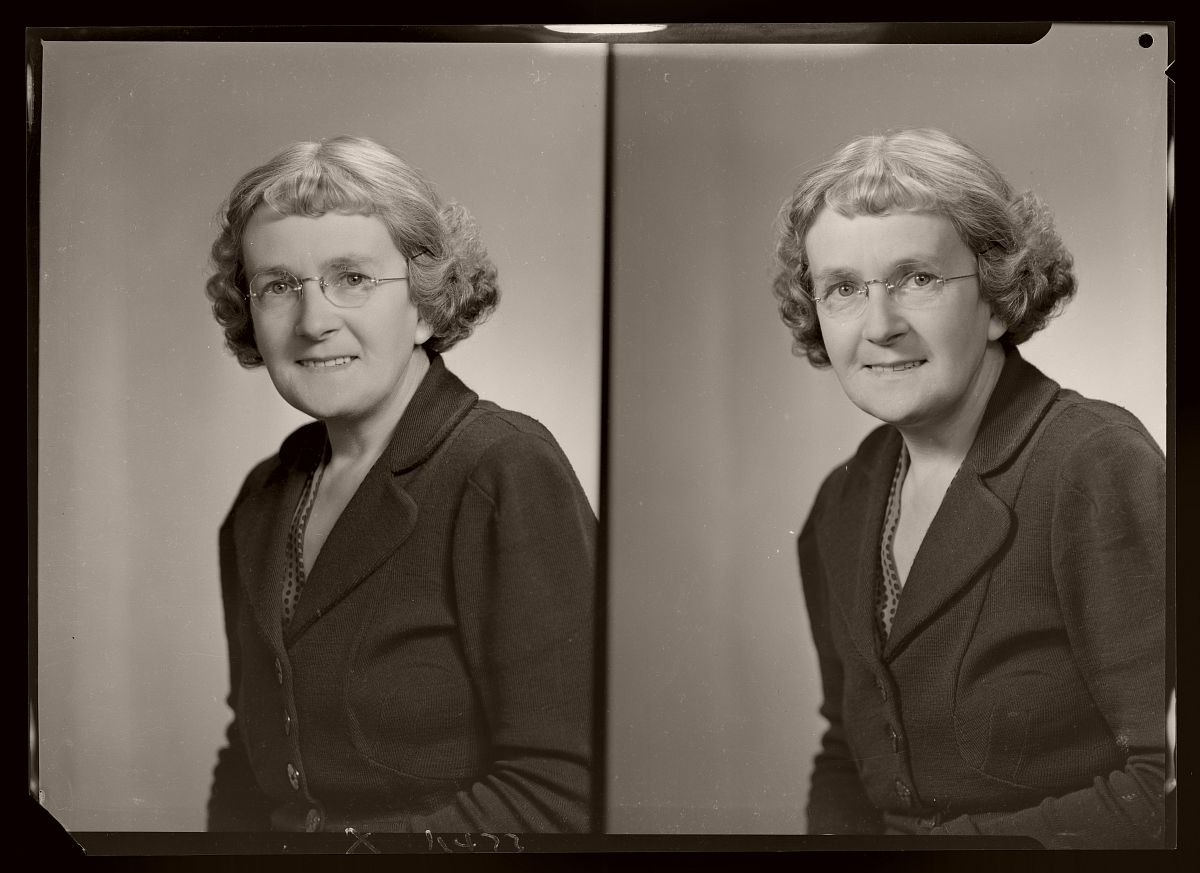

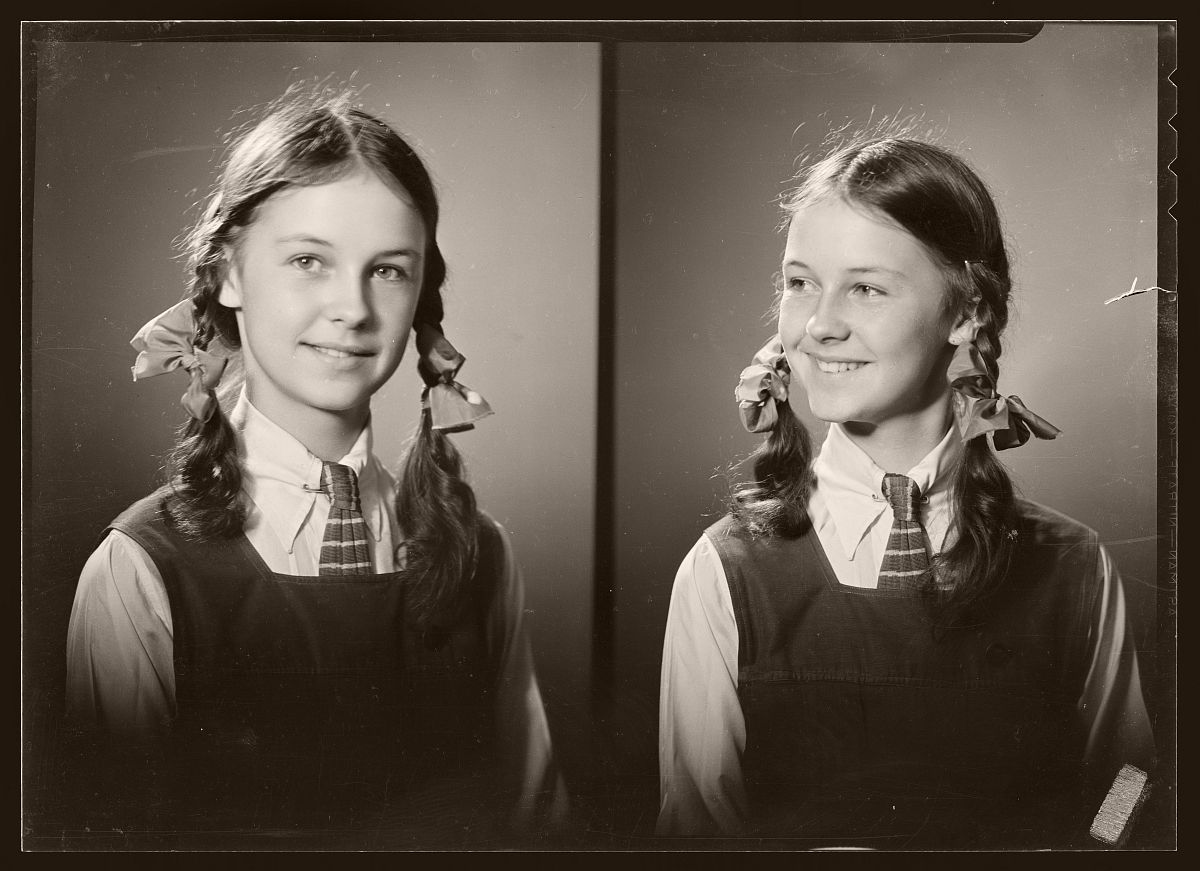

Digby’s most notable subject in the 1930s was the New Zealand Labour Party prime minister, Michael Joseph Savage. The resulting image was published in one of the leading weeklies and quickly became a New Zealand icon, adorning homes throughout the country after Savage’s death in 1940. Another portrait, of George von Zedlitz, won Digby the 1935 New Zealand inter-club competition. However, he was committed to producing work of the highest standard regardless of his subject. This is borne out by the thousands of negatives held at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, which depict accountants, lawyers, débutantes and university graduates as well as numerous soldiers, both American and New Zealand.

In 1939, along with a select group of professionals and some of New Zealand’s leading pictorialists, Digby was heavily involved in selecting prints for a special international photography salon held in connection with the New Zealand Centennial Exhibition in Wellington. He was also a leading light of the Wellington Camera Club, which won the annual inter-club competition for the Bledisloe Cup eight times between 1942 and 1953.

An indication of Digby’s standing at this time was his election as president of the New Zealand Professional Photographers’ Association, a position he held in 1942–43. One of his main tasks was dealing with government officials to seek clarification on labour exemptions for essential services. Besides his photography, he had a passion for literature and music, and in 1945 he helped establish the Wellington Chamber Music Society with Fred Turnovsky.

In the late 1950s Digby moved to Auckland, leaving the management of the studio to an employee. It was sold around 1958; in 1961, together with Digby’s negatives, it was purchased by Ronald and Inge Woolf. Spencer and Edna were divorced in March 1966 and on 16 April that year he married Phyllis Edith Chapman (née Tanner) in Epsom. Apart from a brief managerial role with an international company called Polyfoto, he devoted most of his remaining years to assisting his wife in her retail clothing businesses.

A dapper figure who dressed immaculately with hand-tied bow ties, ‘Dig’ gave tremendous prestige to the art of portraiture in Wellington at a time when flawless complexions were often the handiwork of the retoucher’s pencil and judicious lighting. It is said that when business was slow, he dyed his hair lilac, put on a matching suit and beret and strolled along Lambton Quay to drum up interest. While contemporaries described him as a private person with a perceptive sense of humour, he was a strict disciplinarian in the studio. Those who learnt their trade from him recall how he set the highest professional standards, tearing up prints that did not meet his exacting requirements. Despite this autocratic approach, his employees held him in the greatest respect.