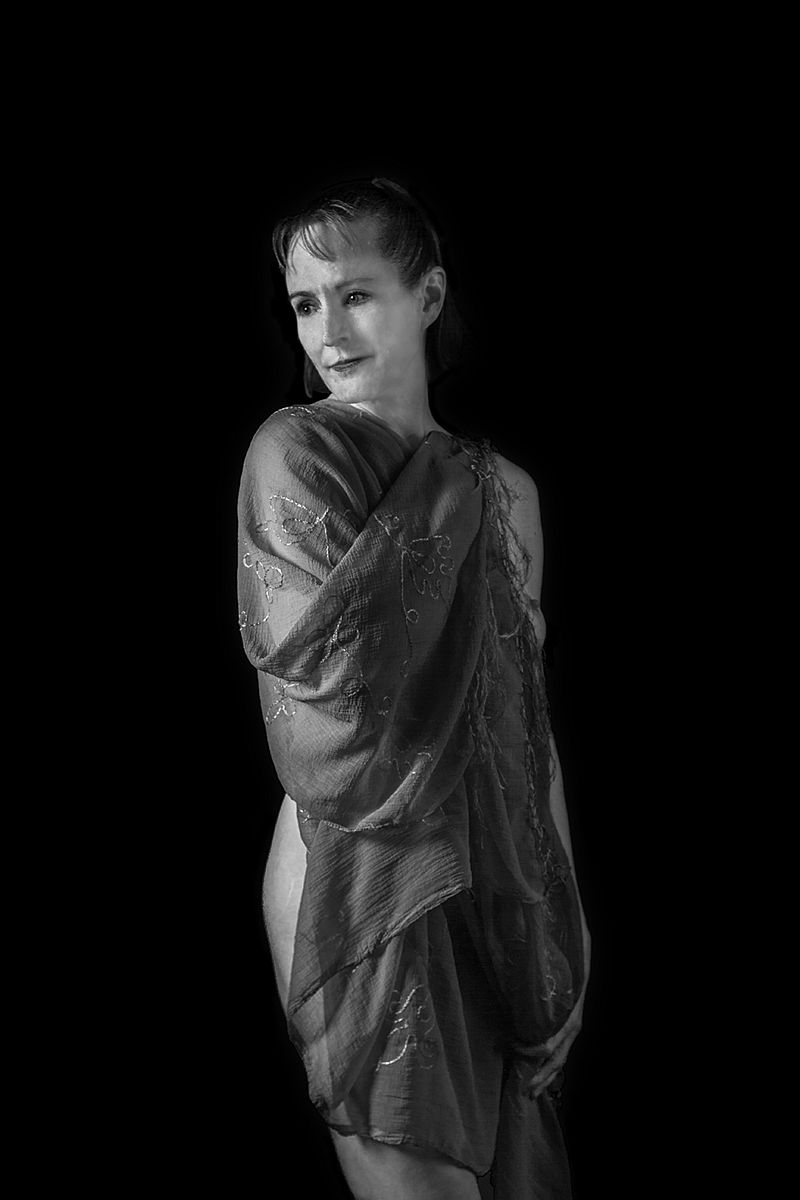

Michael Kelly-DeWitt is a native of Sacramento, CA, and has been working with photography for many years. His photography covers a broad range of subjects: from landscapes and photos of the natural world, to architectural and industrial photography, to style photography, portraiture, and figure study. He’s also shot event photography and music photography, and has had work appear in several shows and galleries in and around Sacramento, California.

1. How and when did you become interested in photography?

I started shooting photography in the late nineties for the simple reason that my older sister had gifted me a Canon Rebel, and I didn’t want her to feel as though I was neglecting the gift. But lo, the more I used the camera, the more I fell in love with the possibilities of the form. And as I used it, I learned more and more about the craft – and I began to notice (and pay serious attention to) the work of other photographers: what they were photographing, how they were composing their images, and how they were lighting their shots. I realized that if I wanted to be a better photographer, I needed to understand what these seasoned photographers were doing, how they were doing it, and why.

2. Is there any artist/photographer who inspired your art?

There have been a number of photographers whose work has inspired and moved me – and many with very different aesthetic and thematic tastes. (The works of Bruce Davidson or Nicholas Nixon would rarely be confused with that of Horst P. Horst or Alfred Eisenstaedt, for example.) But it is Nixon, Horst and Eisenstaedt who have most seriously influenced the development of my portrait work. I can recall first seeing Nixon’s portrait series “The Brown Sisters” online, and later getting a chance to see the works in San Francisco’s MOMA. I was stunned by the emotive impact of the sisters’ faces and body language in progressive photos, as well as by the cumulative emotional effect of seeing them age over time. His body of work was one of the first that truly clued me in to the evocative possibilities of portraiture.

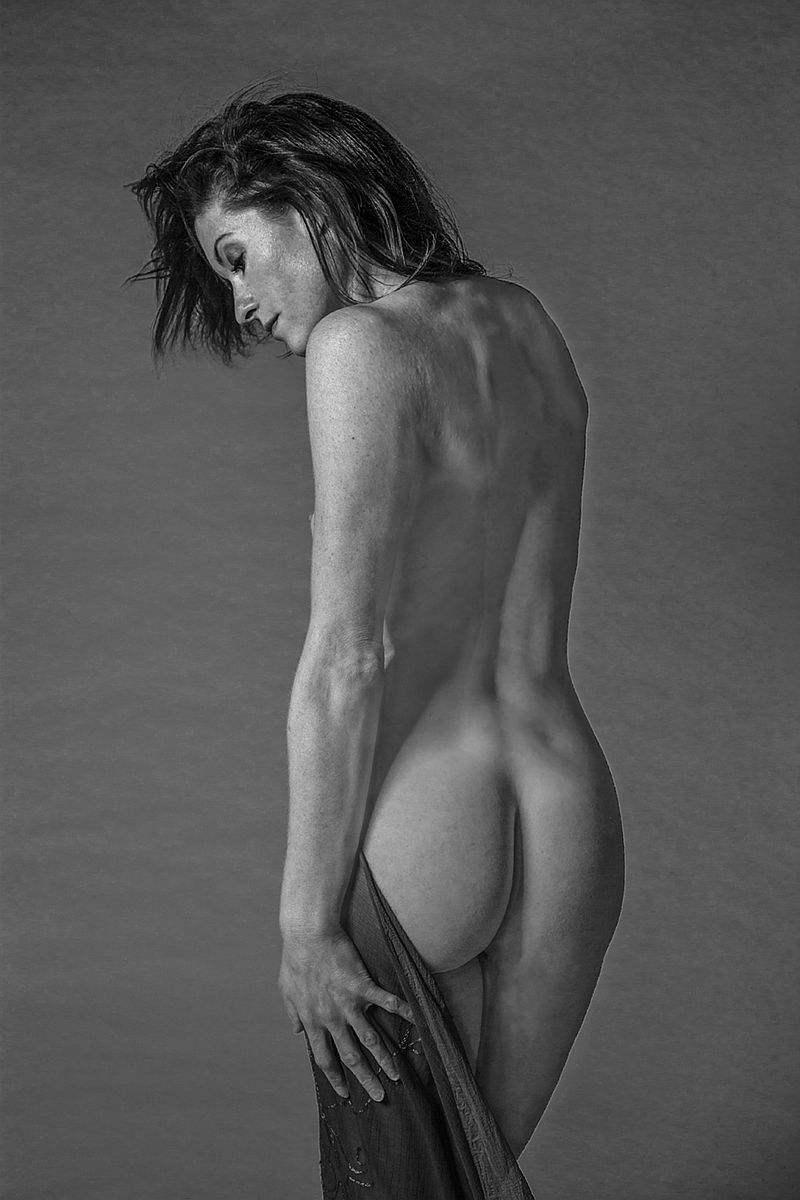

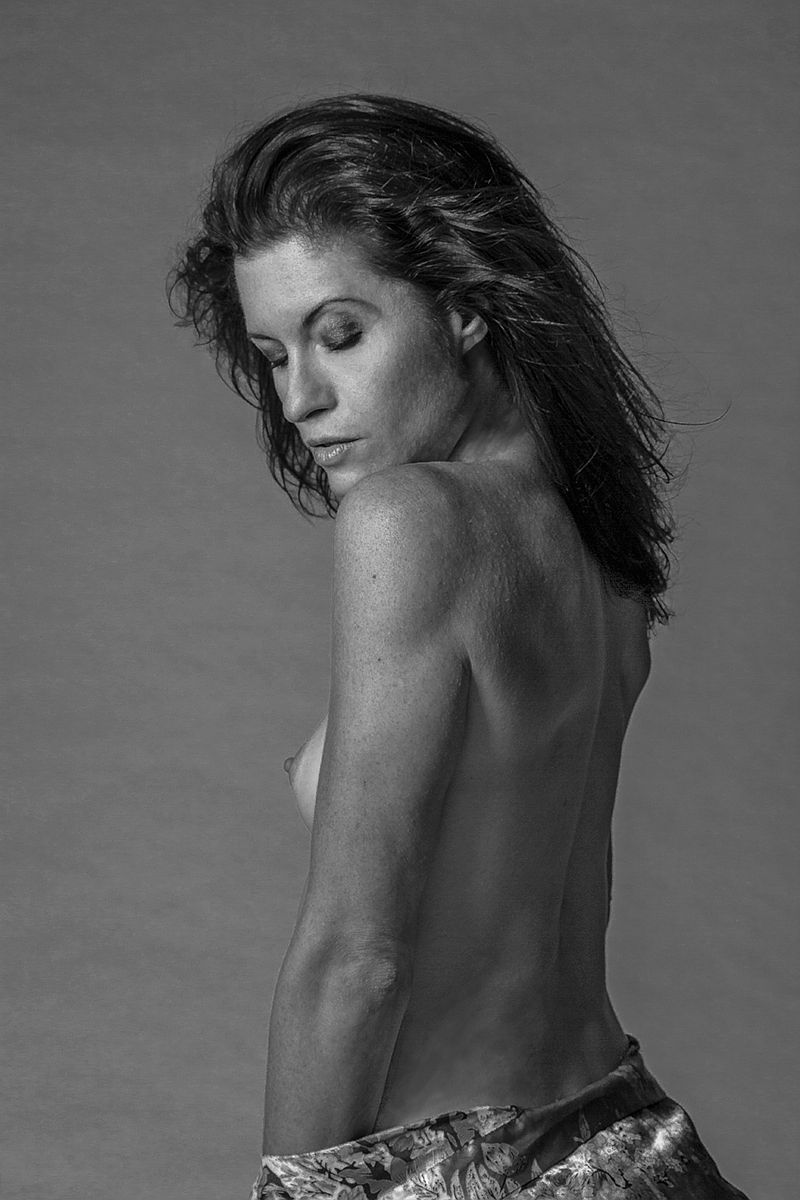

I was in turn affected by the work of Eisenstaedt because his portraiture fused a sense of classical (but creative) composition with a deep empathy for his subjects (whether his subjects were everyday people, or often objectified sexual icons like Marilyn Monroe), and by Horst because his imagery could evoke sensuality and mystery in technically pristine fashion. (His “Mainbocher Corset” a prime example: brilliantly lit and composed, it is – from a craft standpoint – nearly irreproachable. It also drips with sensuality, but does so in a classical way.)

3. Why do you work in black and white rather than color?

The contrast between the rich blacks and the shadings of white, as well as the evocative power of the format, impresses me. I do shoot color in addition to the B&W format, but I feel a particular pull for the latter format because of what I regard as its ability to create an atmosphere of heightened drama through the deployment of those contrasts. The blacks and whites can serve to create an otherworldly sense of drama even when photographing the every day.

4. How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph/series of photographs?

I put hours into any shoot. I begin any set of portraits with an idea – or a series of ideas. These ideas could be a clutch of visual or intellectual themes that I want to capture, or they could simply be a handful of images that I see in my mind. (For me, a shoot isn’t always about an intellectual theme but is as often an exercise in generating or evoking a particular atmosphere or emotion on camera.) When I have a few ideas that I feel are both creatively viable and practically possible, I’ll get in touch with a handful of models and describe my ideas. If a model is interested, we’ll schedule a shoot. I try to incorporate a model’s input and opinions into a shoot – both ahead of time, during the shoot itself, and during the editing process. (With time and increased experience, I’ve come to realize just how much richer a result you get when you talk with a model about the process, and about your artistic goals. Many people that I’ve worked with have had good insight into the modeling side of the process – what works for them, visually and physically – as well as what might visually contribute to the project’s overall goals.)

I usually arrive early for any shoot: I hate the feeling of being rushed, and so allow myself plenty of time to set up my lighting, any backdrops, and any objects that will be used in the shoot. The shoots themselves usually last three to four hours: less time and I find myself feeling rushed; more than that, however, is usually just padding.

My shoots are small in scale: it’s usually just me and the model. I don’t have a team of stylists and makeup artists with me. Not because I have an academic or philosophical bent against having a large scale photo squad, but because of practical monetary concerns. (Stylists and makeup artists – especially good stylists and makeup artists – cost more than I can afford.)

After a shoot, I can spend hours and hours (and hours) editing images over a span of weeks. (Or months.) I’ll usually look through the photos in the day or two following a shoot, select a clutch of images that immediately strike me, and edit them. And then I often set them aside for a time, and return to them later – a week or two weeks later, or even a month. I’m an incredibly slow editor, but I do find that taking my time – and revisiting images at intervals – allows me to see new things in my images.

5. Where is your photography going? What projects would you like to accomplish?

I aim to continue working in a multiple formats and styles – a bit of variety helps to keep me interested. I would like to shoot more portraiture that incorporates an emotional element, and that emphasizes the lines of the human form.

Website: www.michaelkellydewitt.net