If you’ve ever bemoaned the fact that you share a bathroom with several family members or housemates, you’re not alone. Most New Yorkers live in apartments and most units have just a single bathroom. A hundred and fifty years ago, however, the situation was much worse. At the time, New Yorkers had just a few choices when it came to taking care of their lavatory needs and by modern standards, none of the options were appealing—visit an outhouse or use a chamber pot. Nevertheless, indoor toilets proved slow to gain popularity when they were first introduced in the second half of the nineteenth century. Initially, many residents feared the newfangled invention would bring poisonous gases into their homes, leading to illness and even death.

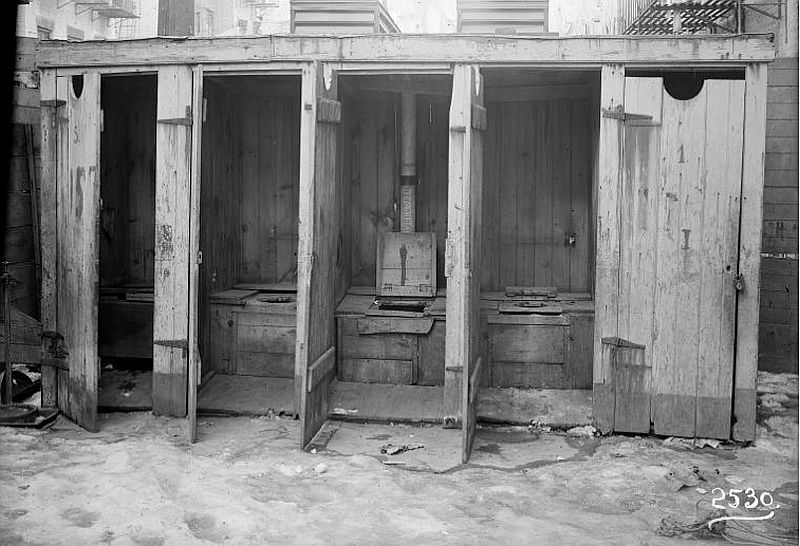

Until the late nineteenth century, most New Yorkers relied solely on outhouses located in backyards and alleys. While some residents had their own private outhouses, anyone living in a tenement would have shared facilities with their neighbors. The outhouse/resident ratio varied, but most tenements had just three to four outhouses, and as reported in Jacob Riis’s “How the Other Half Lives,” in the nineteenth century, it was not uncommon to find over 100 people living in a single tenement building. This meant that people often shared a single outhouse with anywhere from 25 to 30 of their neighbors, making long line-ups and limited privacy common problems. As one might expect, most tenement outhouses were also teeming with rats and other vermin and were a major source of disease.

If bathroom breaks were undesirable in the daytime hours, at night, especially in the dead of winter when running down several flights of stairs to street level posed additional dangers, most city residents turned to their chamber pots. Chamber pots, usually earthenware vessels, were typically stored under beds. Since most tenements had little or no ventilation, however, the stench from the chamber pots could quickly become unbearable. To help control the stench, chamber pots had to be emptied into backyard outhouses on a regular basis. Unsurprisingly, carrying pots full of human waste through the dark and narrow halls of a tenement was also no one’s favorite chore.

Outside the city, outhouses were usually temporary structures built over a hole in the ground. As the holes filled up, the outhouses were simply moved to a new location and the holes covered over with fresh soil. In urban areas, limited space meant that most outhouses were permanent structures. This also meant that removing human waste was a thriving business in the nineteenth-century New York.

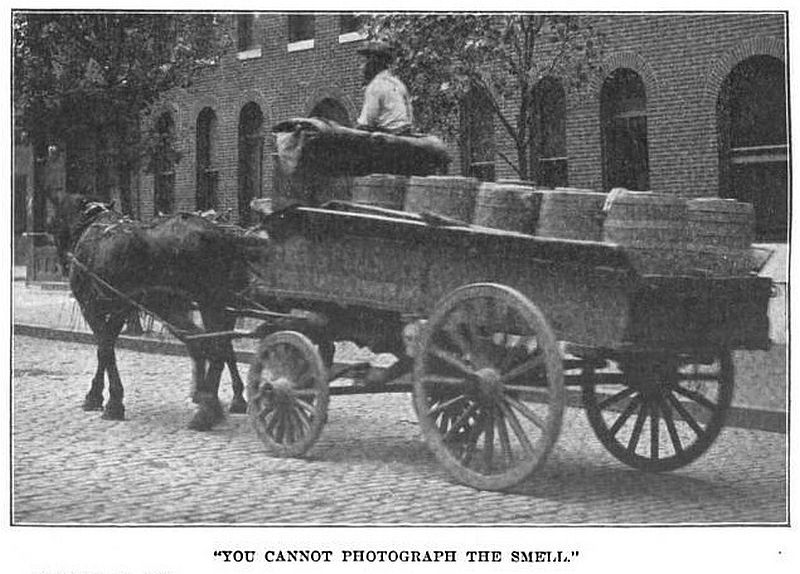

At the time, human waste was euphemistically known as “night soil.” This is presumably because the so-called night soil cart men, who worked for companies that had been lucky enough to win a coveted city contract for waste removal, made their living largely after dark. Their unenviable job involved shoveling waste from the city’s outhouses into carts (sometimes other garbage and animal carcasses would also be collected) and then disposing of the contents.

Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Row of outhouses” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1902 – 1914.

via 6sqft