Between 1938 and 1950, National City Lines and its subsidiaries, American City Lines and Pacific City Lines—with investment from GM, Firestone Tire, Standard Oil of California (through a subsidiary), Federal Engineering, Phillips Petroleum, and Mack Trucks—gained control of additional transit systems in about 25 cities. Systems included St. Louis, Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Oakland. NCL often converted streetcars to bus operations in that period, although electric traction was preserved or expanded in some locations. Other systems, such as San Diego’s, were converted by outgrowths of the City Lines. Most of the companies involved were convicted in 1949 of conspiracy to monopolize interstate commerce in the sale of buses, fuel, and supplies to NCL subsidiaries, but were acquitted of conspiring to monopolize the transit industry.

The story as an urban legend has been written about by Martha Bianco, Scott Bottles, Sy Adler, Jonathan Richmond, Cliff Slater and Robert Post. It has been explored several times in print, film, and other media, notably in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Taken for a Ride, Internal Combustion, and The End of Suburbia.

Only a handful of U.S. cities, including San Francisco, New Orleans, Newark, Cleveland, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Boston, have surviving legacy rail urban transport systems based on streetcars, although their systems are significantly smaller than they once were. Other cities are re-introducing streetcars. In some cases, the streetcars do not actually ride on the street. Boston had all of its downtown lines elevated or buried by the mid-1920s, and most of the surviving lines at grade operate on their own right of way. However, San Francisco’s and Philadelphia’s lines do have large portions of the route that ride on the street as well as using tunnels.

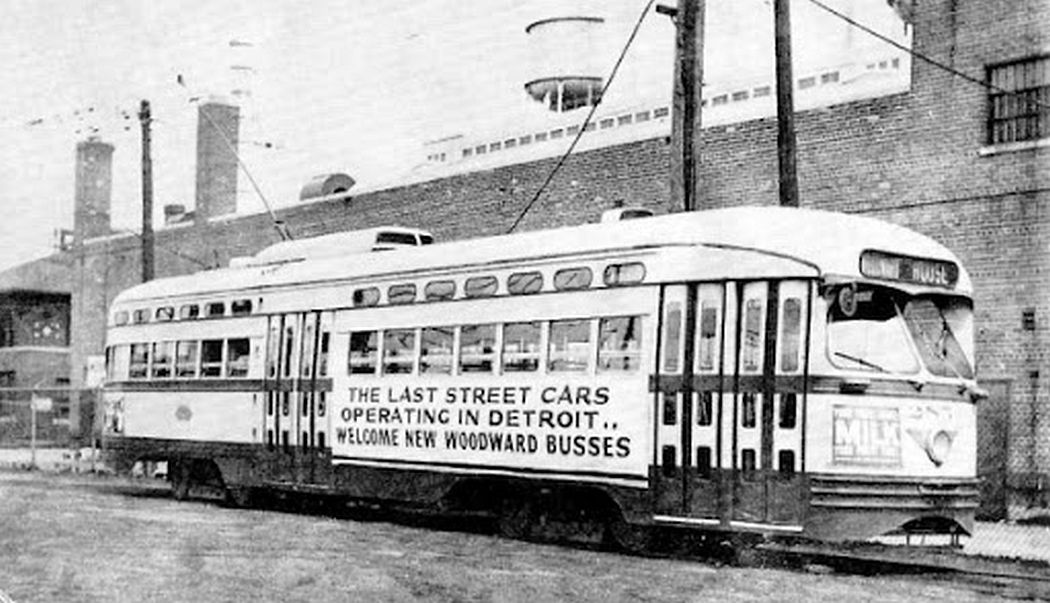

One of Detroit’s final streetcars, shown as part of a special parade in 1956. (Dave’s Electric Railroads —Stephen M. Scalzo collection)

Decommissioned streetcars awaiting destruction in Los Angeles, 1956. (Los Angeles Times photographic archive)