Since his first trip to Haiti in 1997 Thomas Kern(*1965) has repeatedly returned there to capture the turbulent history of the former Pearl of the Antilles. Reserved and at the same time close to the people, he documents everyday life in one of the world’s poorest countries in a classical black-and-white. His photographs testify to the great individual efforts made and the tiny joys experienced in a country marked by natural catastrophes, political instability and a creeping ecological disaster. Furthermore, they tell of the history of slavery and of the apparent escape into the spiritual world of voodoo.

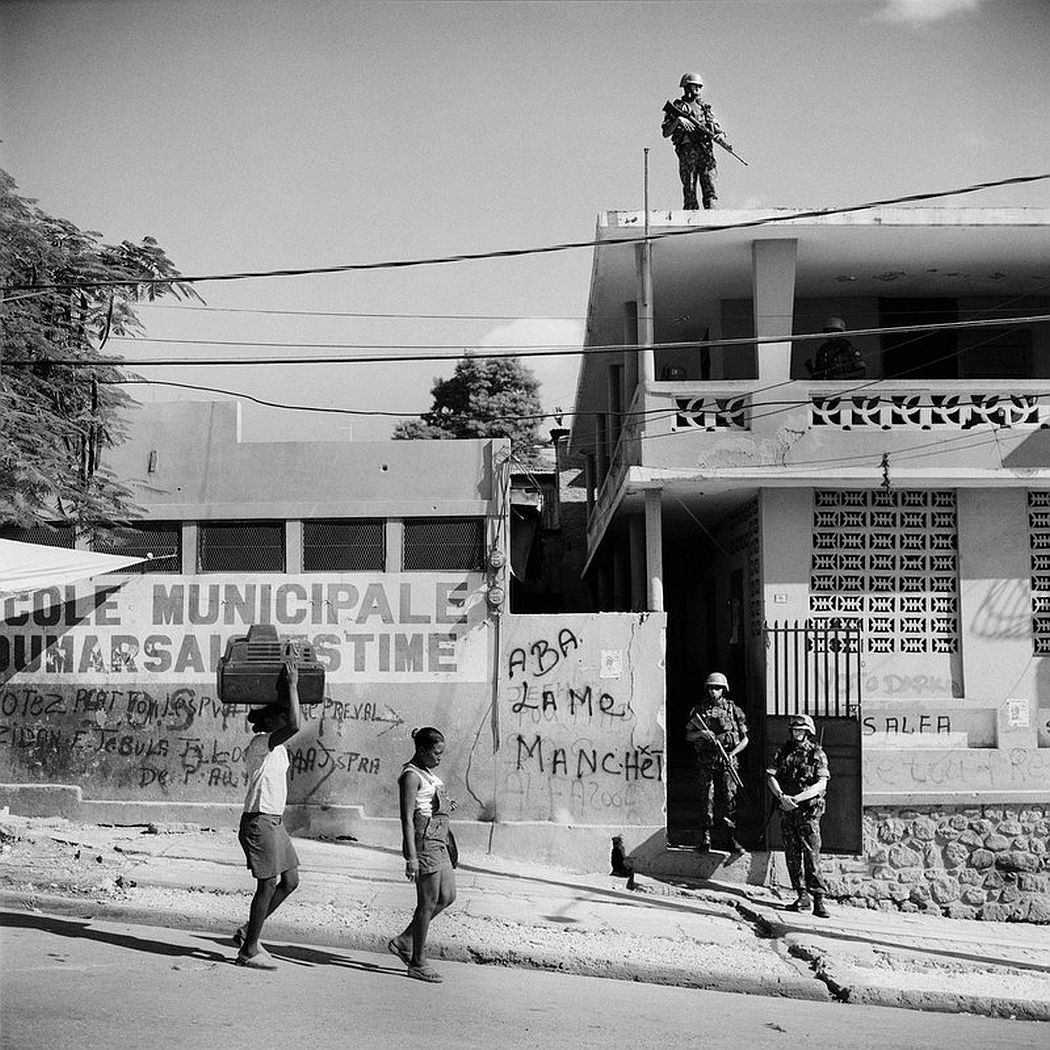

Thomas Kern, co-founder of the Swiss Photo Agency Lookat Photos, made a name for himself in the 1990s with reportages on the impacts of war and conflict – in Northern Ireland, for example, or in the former Yugoslavia. In 1997 he travelled to Haiti for the first time on a commission from the cultural magazine du, shortly before he moved to San Francisco, where he worked as a freelance photographer for the following eight years. Since that first encounter, the country in the Caribbean has not let go of him, a country whose widespread image is marked, above all, by American media reports on catastrophes there. As Haiti is only about one hour by plane from Miami, political unrest, riots with burning car tyres, or the annual storms are always worth a cover story, although the complex political, economic and social background is often faded out.

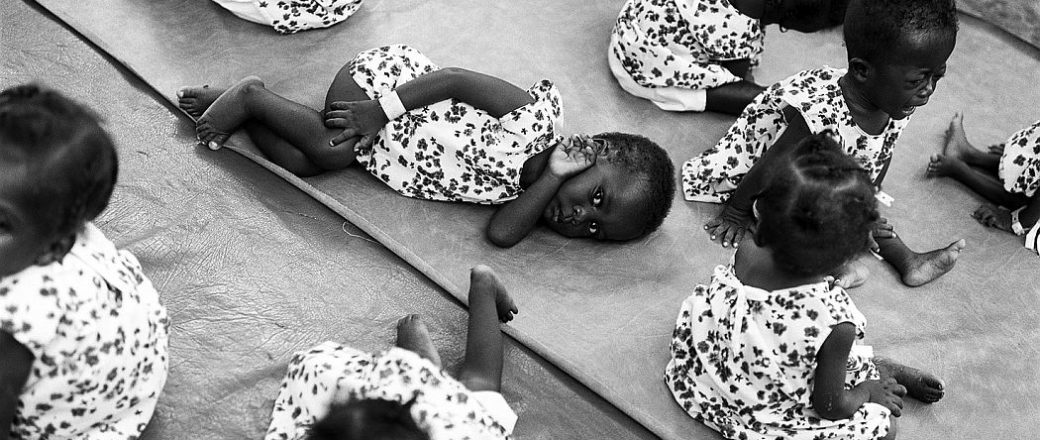

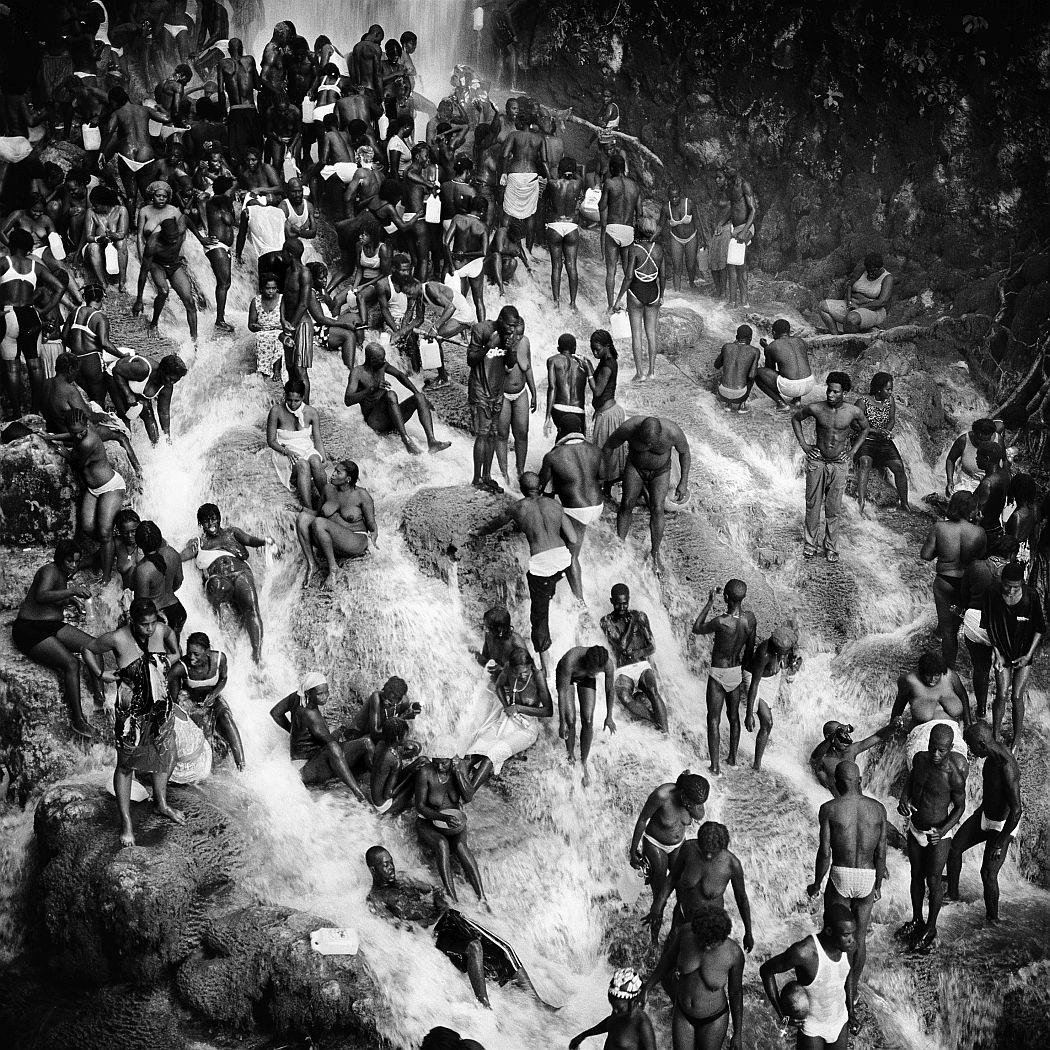

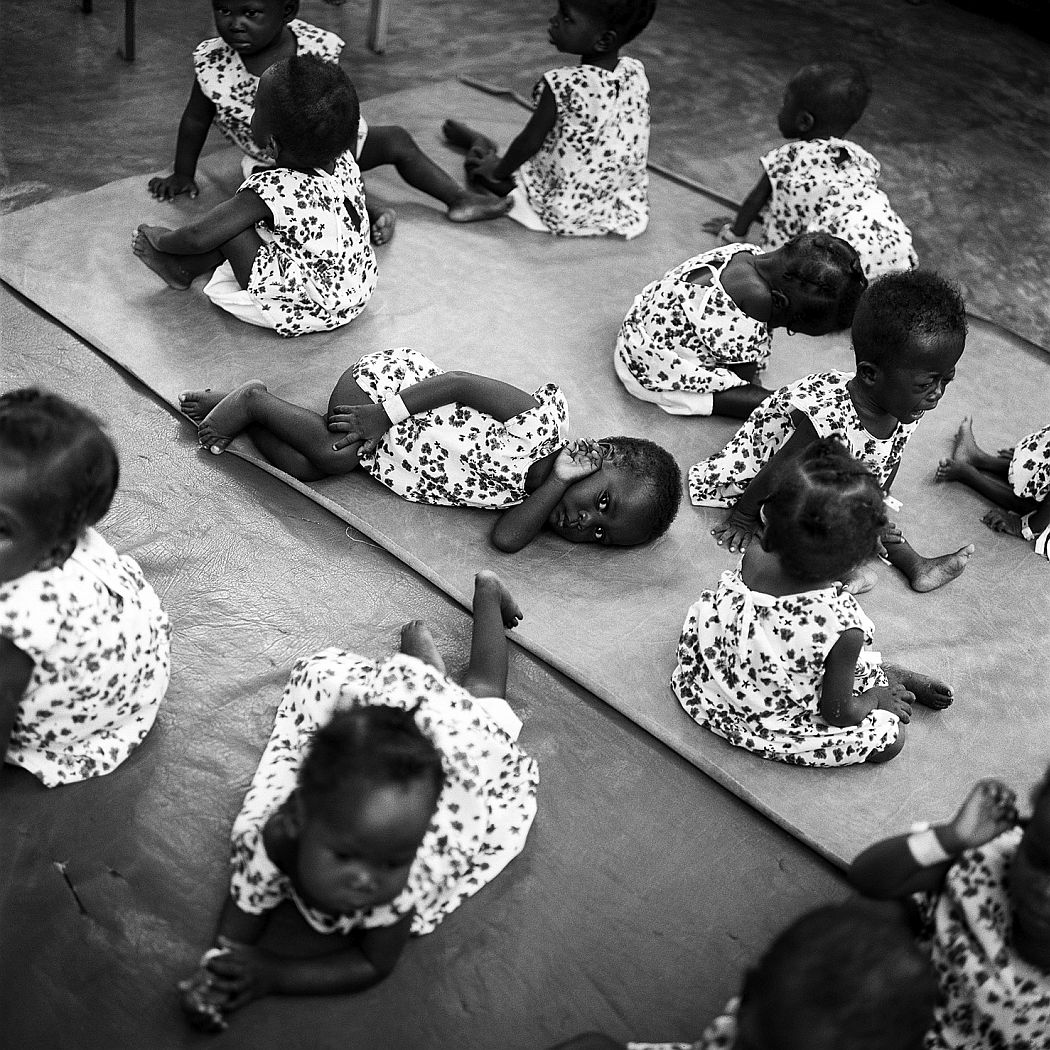

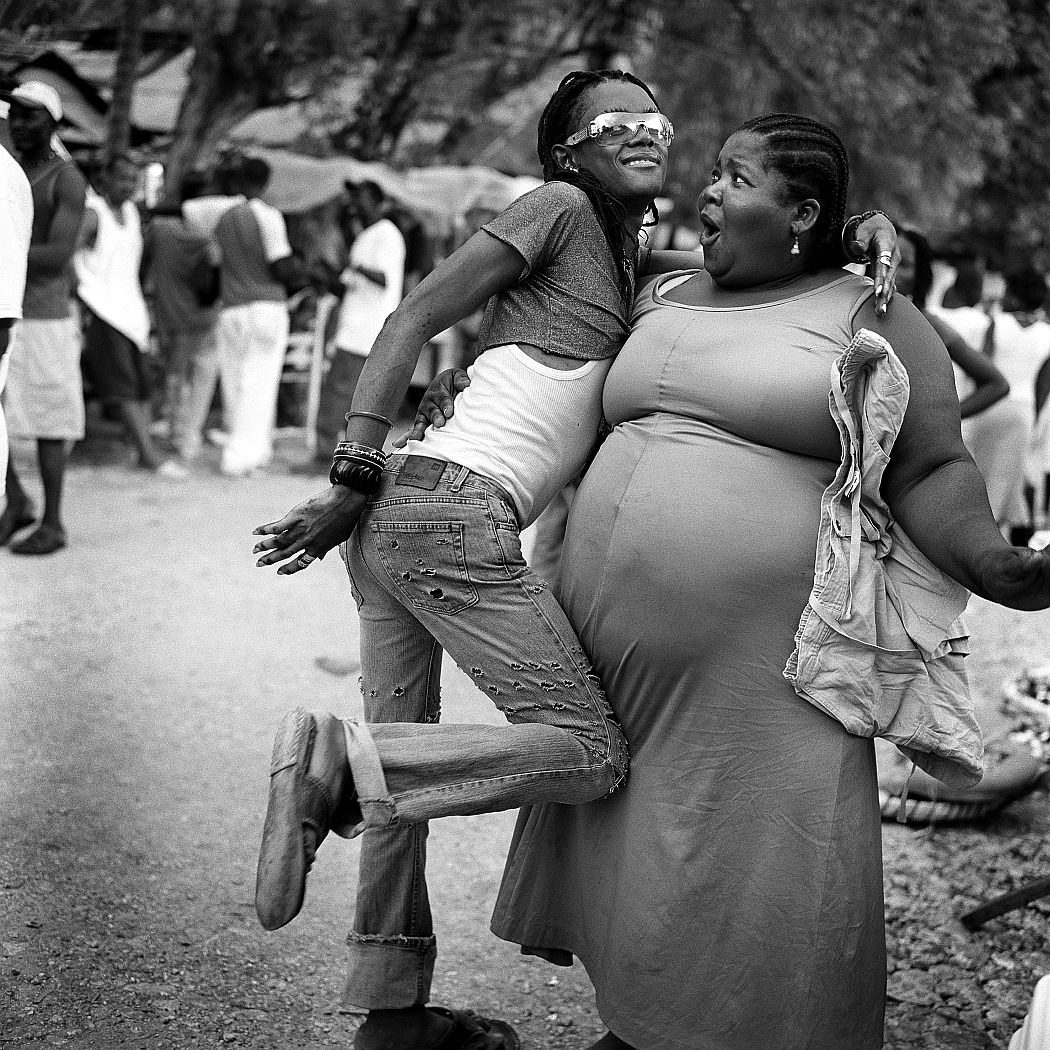

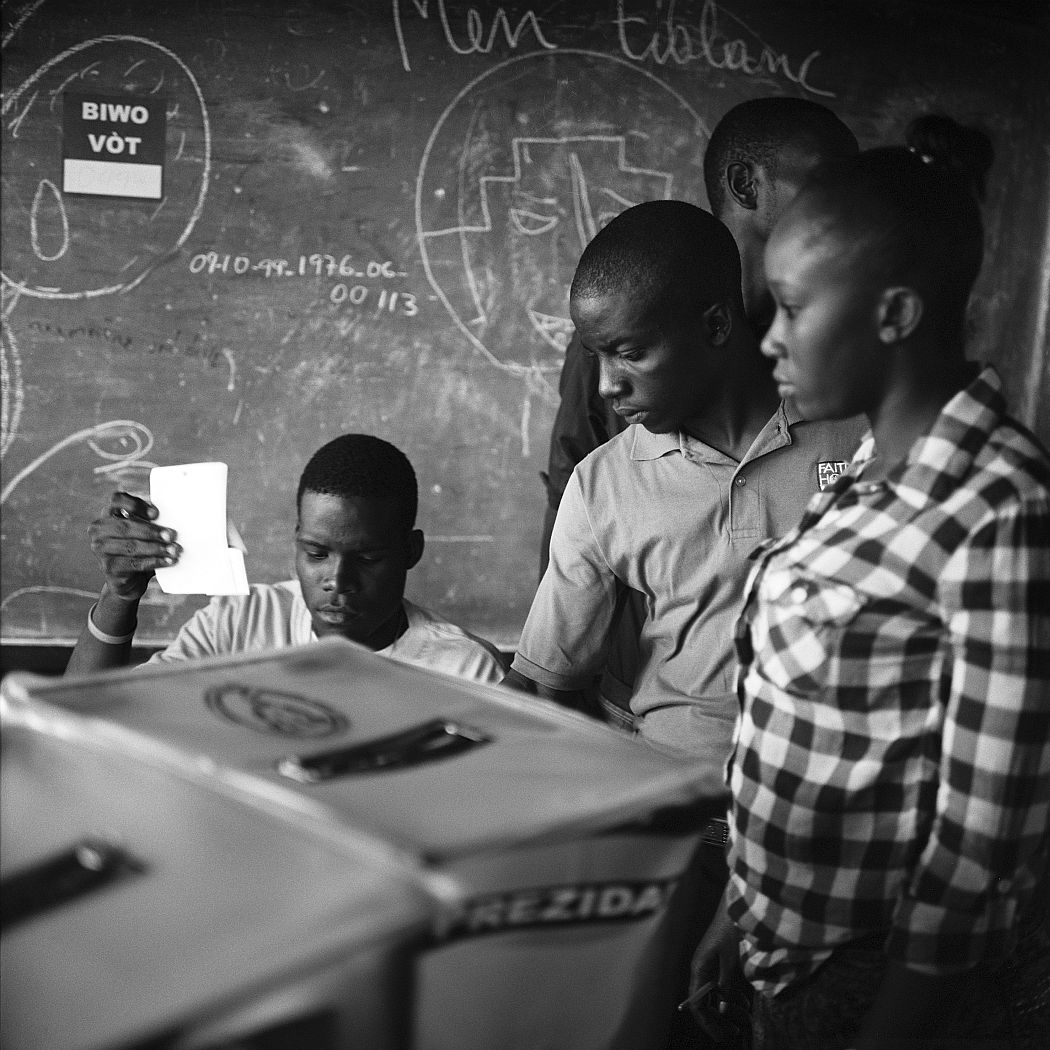

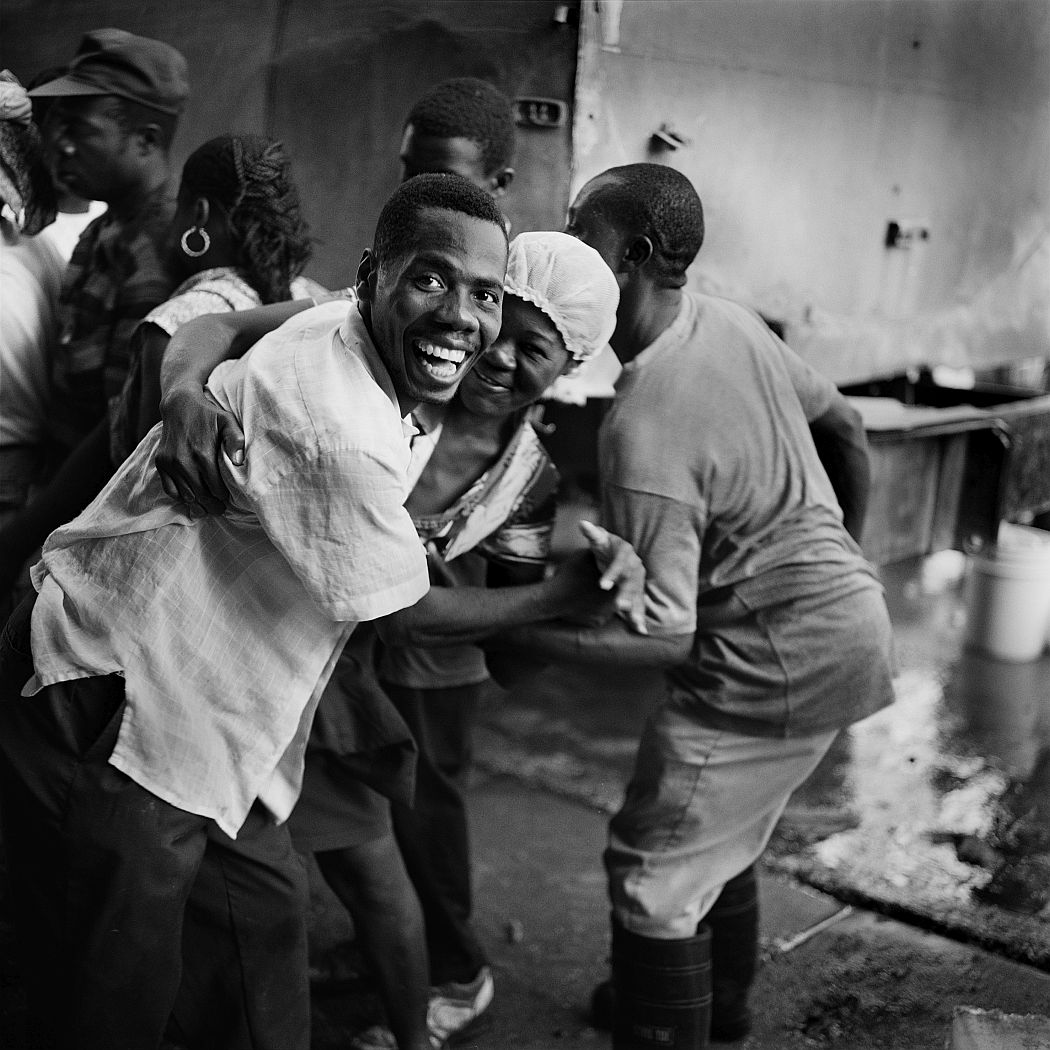

Thomas Kern reacts particularly sensitively to the common clichés, aware that he too is just an outsider who can never really do justice to the country’s complexities and contradictions. Above all he does not wish to just foreground Haiti’s scandalous poverty – it is always present in the background, one way or the other. On the contrary, he prefers to lead us into a chaotic scenario full of strange phenomena. And he does this by simple deliberately chosen means – using a Rolleiflex without interchangeable lenses and analogue black-and-white film. In instantaneous takes that often exhibit surreal traits, he renders everyday life perceptible in all its facets. Kern takes his photographs spontaneously, yet always in a square format that suggests stability and peace, even if confusion prevails within the image: different pictorial levels are superimposed, movements are not sharp, figures are cropped or only visible as dark shadows. This precarious balance between standstill and explosive dynamism is a central theme that runs through all his photographs. The photographer does not become involved in the events, he observes them, allowing himself all the while to be guided by his own impressions. Despite this apparent distance, Kern’s photographs draw us directly into the real happenings of everyday life in Haiti, a field of tension between resignation and irrepressible vitality. The Haitian writer Yanick Lahens comments on Thomas Kern’s photographs: “In Haiti you have to accept it all: the shade and the extremely beautiful lights. They continually guide us back again to the shadow and light in ourselves. The creativity keeps us alive; it is our oxygen. We turn the world upside down, like at Carneval. Through mockery, beauty, and grandeur. Some photos say that in their own special way. We open up unexpected brackets and thumb our noses at the misfortune.”

This misfortune extends far back into the 19th century, when Haiti won its independence from the French colonial power, eliminated slavery and thus became the first free state in Latin America. Since then, the country’s history has been accompanied by violent struggles, and the governments and dictators that replaced one another in swift succession have contributed little or nothing towards stabilising the country or advancing it economically. Instead they have used their power shamelessly for their own personal enrichment. To this very day, the political system of the first “black” republic is marked by opportunism, nepotism and corruption.

Before Haiti was colonised by Spain and France, the island state was a kind of tropical Garden of Eden, almost 90% of it covered by trees. Today it is only 2% and still declining, because wood, made into charcoal, is and will continue to be one of the country’s most important sources of energy. The progressive clearing of the forests leads to increasing soil erosion, reducing the amount utilisable for agriculture and thus greatly restricting the production of food. Then there are the regular natural catastrophes, such as drought, hurricanes and flooding.

In the acute emergency after the earthquake on 12 January 2010, in which more than 300’000 people lost their lives and more than a million were made homeless, the state also proved to be unable to respond appropriately. It left management of the crisis to countless international organisations who inundated the country to provide the urgently needed emergency aid. But despite the additional billions promised for reconstruction, of which a large part never arrived in Haiti or else seeped into the mire of corruption, a food shortage and widespread unemployment still prevail today. Clean drinking water is scarce, environmental pollution is increasing rapidly, and the population – except for a small wealthy minority – is suffering from extreme poverty.

Today the country that was once among the richest territories of the French colonial realm is totally dependent on foreign aid. A dependence from which Haiti has not been able to free itself. The country has preserved a kind of slavish mentality, preferring to hold others responsible for the misery rather than taking things into their own hands. The voodoo religion does not offer a way out of this tragic and paradoxical situation. The cult of gods and spirits brought by slaves from Africa during the colonisation period, and in which rituals of sacrifice and purification play a major role, is still practiced by a large part of the population today, parallel to Catholicism. Voodoo offers people the possibility of escape into a spiritual world that gives them comfort, at least for a certain time, but in which they can also lose themselves. It is above all an escape which helps them to endure the real problems of life or at least repress them for a while.

The exhibition at the Fotostiftung Schweiz brings together more than a hundred, partly large format images taken over the past twenty years or so.

With the support of the Bundesamt für Kultur, Berne, the Friends of the Fotostiftung Schweiz and the Georg and Bertha Schwyzer-Winiker Foundation.

The book “Thomas Kern – Haiti. The Perpetual Liberation”, with texts in German, English and Creole by Thomas Kern, Georg Brunold, Yanick Lahens and Felix Morisseau-Leroy will be published to accompany the exhibition by Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich (CHF 39).

Thomas Kern

Haiti. The Perpetual Liberation

17 Sep 2016 – 29 Jan 2017

Fotostiftung Schweiz

Grüzenstr. 45

8400 Winterthur

www.fotostiftung.ch