This year marks the 25th anniversary of South Africa’s first democratic elections, followed by the inauguration of Nelson Mandela as president in 1994. This historic event marked the end of apartheid: a regime of institutionalised racial segregation that was in effect from 1948 to 1991. South African photographer Santu Mofokeng (b. 1956) documented the everyday lives of rural sharecroppers and of labourers in the townships. At a time when propaganda dominated the media, his images offer a more nuanced understanding of daily life under apartheid and after. Foam presents a major monographic exhibition with previously unseen works from the photographer’s personal archives. The exhibition brings together 11 visual stories that each narrate an hour, a week, or sometimes years of everyday life in a rapidly changing political climate.

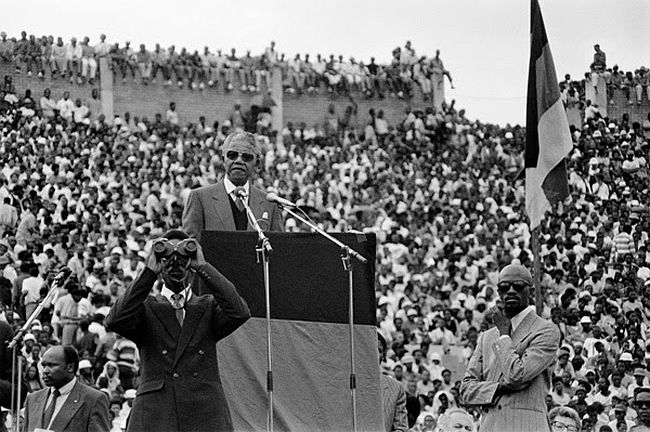

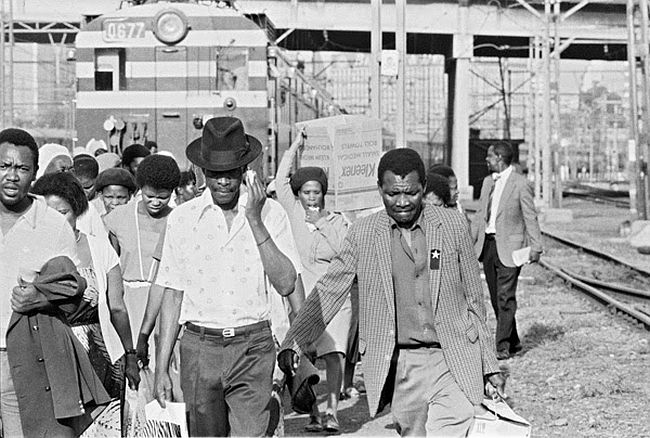

Mofokeng grew up in Soweto, a township on the outskirts of Johannesburg. As a black photographer under apartheid, he would be one of the few to document various South African communities up close and from within. The exhibition brings together a number of important photographic essays, including Mofokeng’s first and most celebrated visual story Train Church (1986): a report on the spontaneous religious rituals that occurred in the commuter train between Soweto and Johannesburg. Other photos portray street life and the shebeens (illicit drinking establishments) in the townships of Soweto and Dukathole. The exhibition also presents early journalistic images of unionization and political rallies that formed the prelude to the eventual abolishment of apartheid and the election of Nelson Mandela as president in 1994. Together, hundreds of photographs paint a dynamic portrait of a complex society in a state of transition.

The life of Santu Mofokeng was marked by inequality and deep political divisions from the outset. The photographer grew up in poverty and spent his school years at the Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto; one of the hotbeds of the violently suppressed Soweto uprising in 1976. After working as an assistant in the dark rooms of various newspapers, in 1985 he joined the photo agency Afrapix: a photographers’ collective that documented inequality and protest movements in South Africa. His work was among others published in New Nation, an anti-apartheid weekly that was censured by the South African government in 1988.

Despite the political stance of Afrapix and New Nation, Mofokeng never considered himself an activist – or even a photo journalist. He cherished a deep dislike for so-called ‘struggle photography’, which he considered an easy way of making money by supplying spectacular front-page images of civil disobedience or police violence. Besides, without a car or easy access to a dark room, Mofokeng often failed to respond promptly to events of the day. His profound interest in everyday life moreover meant that he would sometimes linger in a single place for weeks on end. For this reason, Mofokeng started work as a research photographer at the University of Witwatersrand in 1988. For the next ten years he supplied visual material for a study into the consequences of segregated land ownership in the rural town of Bloemhof. He portrayed the relatives and community that surrounded the elderly sharecropper Kas Maine, resulting in the acclaimed series Labour Tenancy, Concert at Sewefontein and Funeral – all of which are on display in Foam. At last Mofokeng managed to find the space and the resources to work the way he preferred: over longer periods of time and without succumbing to the one dimensionality of propaganda and sensationalism.

Santu Mofokeng has always been acutely aware of his position as an image maker in a deeply divided society. The apartheid regime treated photography as a propaganda tool and used censure to influence the public opinion, while protest movements mobilized the medium to expose acts of violence, inequalityand suppression. Images of the Sharpeville Massacre and the injured child Hector Pieterson during the Soweto uprising were beamed around the world. Mofokeng’s images are an indirect response to such (visual) violence, and its underlying black-and-white mentality. By contrast, his photographs are observant, intuitive, intimate and ambivalent. With this the work does justice to the complexity of South African history, while continuing to question the power of images today.

Santu Mofokeng

Stories

15 February – 28 April 2019

Foam

Keizersgracht 609

1017 DS Amsterdam

+31 20 5516500

foam.org

From the series Politics. Photograph by Santu Mofokeng (b.1956) © Santu Mofokeng Foundation. Image courtesy of Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg and Steidl GmbH.

From the series Train Church. Photograph by Santu Mofokeng (b.1956) © Santu Mofokeng Foundation. Image courtesy of Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg and Steidl GmbH.

From the series Train Church. Photograph by Santu Mofokeng (b.1956) © Santu Mofokeng Foundation. Image courtesy of Lunetta Bartz, MAKER, Johannesburg and Steidl GmbH.