Nicéphore Niépce (1765 – 1833) was a French inventor of photography and a pioneer in that field.

The date of Niépce’s first photographic experiments is uncertain. He was led to them by his interest in the new art of lithography, for which he realized he lacked the necessary skill and artistic ability, and by his acquaintance with the camera obscura, a drawing aid which was popular among affluent dilettantes in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. The camera obscura’s beautiful but fleeting little “light paintings” inspired a number of people, including Thomas Wedgwood and Henry Fox Talbot, to seek some way of capturing them more easily and effectively than could be done by tracing over them with a pencil.

Letters to his sister-in-law around 1816 indicate that Niépce had managed to capture small camera images on paper coated with silver chloride, making him apparently the first to have any success at all in such an attempt, but the results were negatives, dark where they should be light and vice versa, and he could find no way to stop them from darkening all over when brought into the light for viewing.

Niépce turned his attention to other substances that were affected by light, eventually concentrating on Bitumen of Judea, a naturally occurring asphalt that had been used for various purposes since ancient times. In Niépce’s time, it was used by artists as an acid-resistant coating on copper plates for making etchings. The artist scratched a drawing through the coating, then bathed the plate in acid to etch the exposed areas, then removed the coating with a solvent and used the plate to print ink copies of the drawing onto paper. What interested Niépce was the fact that the bitumen coating became less soluble after it had been left exposed to light.

Niépce dissolved bitumen in lavender oil, a solvent often used in varnishes, and thinly coated it onto a lithographic stone or a sheet of metal or glass. After the coating had dried, a test subject, typically an engraving printed on paper, was laid over the surface in close contact and the two were put out in direct sunlight. After sufficient exposure, the solvent could be used to rinse away only the unhardened bitumen that had been shielded from light by lines or dark areas in the test subject. The parts of the surface thus laid bare could then be etched with acid, or the remaining bitumen could serve as the water-repellent material in lithographic printing.

Niépce called his process heliography, which literally means “sun drawing”. In 1822, he used it to create what is believed to have been the world’s first permanent photographic image, a contact-exposed copy of an engraving of Pope Pius VII, but it was later destroyed when Niépce attempted to make prints from it. The earliest surviving photographic artifacts by Niépce, made in 1825, are copies of a 17th-century engraving of a man with a horse and of what may be an etching or engraving of a woman with a spinning wheel. They are simply sheets of plain paper printed with ink in a printing press, like ordinary etchings, engravings, or lithographs, but the plates used to print them were created photographically by Niépce’s process rather than by laborious and inexact hand-engraving or drawing on lithographic stones. They are, in essence, the oldest photocopies. One example of the print of the man with a horse and two examples of the print of the woman with the spinning wheel are known to have survived. The former is in the collection of the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris and the latter two are in a private collection in the United States.

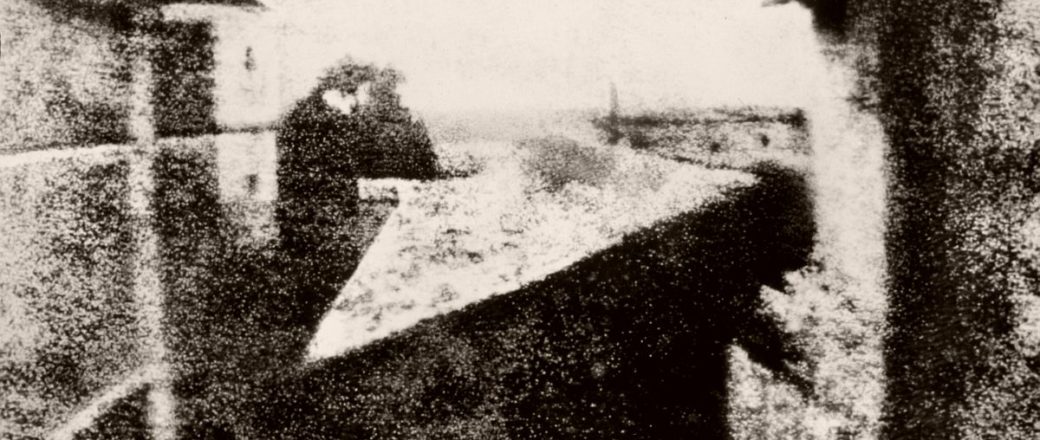

Niépce’s correspondence with his brother Claude has preserved the fact that his first real success in using bitumen to create a permanent photograph of the image in a camera obscura came in 1824. That photograph, made on the surface of a lithographic stone, was later effaced. In 1826 or 1827 he again photographed the same scene, the view from a window in his house, on a sheet of bitumen-coated pewter. The result has survived and is now the oldest known camera photograph still in existence. The historic image had seemingly been lost early in the 20th century, but photography historian Helmut Gernsheim succeeded in tracking it down in 1952. The exposure time required to make it is usually said to have been eight or nine hours, but that is a mid-20th century assumption based largely on the fact that the sun lights the buildings on opposite sides, as if from an arc across the sky, indicating an essentially day-long exposure. A later researcher who used Niépce’s notes and historically correct materials to recreate his processes found that in fact several days of exposure in the camera were needed to adequately capture such an image on a bitumen-coated plate.

In 1829, Niépce entered into a partnership with Louis Daguerre, who was also seeking a means of creating permanent photographic images with a camera. Together, they developed the physautotype, an improved process that used lavender oil distillate as the photosensitive substance. The partnership lasted until Niépce’s death in 1833, after which Daguerre continued to experiment, eventually working out a process that only superficially resembled Niépce’s. He named it the “daguerréotype”, after himself. In 1839 he managed to get the government of France to purchase his invention on behalf of the people of France. The French government agreed to award Daguerre a yearly stipend of 6,000 Francs for the rest of his life, and to give the estate of Niépce 4,000 Francs yearly. This arrangement rankled Niépce’s son, who claimed Daguerre was reaping all the benefits of his father’s work. In some ways, he was right—for many years, Niépce received little credit for his contribution. Later historians have reclaimed Niépce from relative obscurity, and it is now generally recognized that his “heliography” was the first successful example of what we now call “photography”: the creation of a reasonably light-fast and permanent image by the action of light on a light-sensitive surface and subsequent processing.

Although initially ignored amid the excitement caused by the introduction of the daguerreotype, and far too insensitive to be practical for making photographs with a camera, the utility of Niépce’s original process for its primary purpose was eventually realized. From the 1850s until well into the 20th century, a thin coating of bitumen was widely used as a slow but very effective and economical photoresist for making printing plates.

View from the Window at Le Gras (1826 or 1827), the earliest surviving photograph of a real-world scene, made using a camera obscura. Nicéphore Niépce