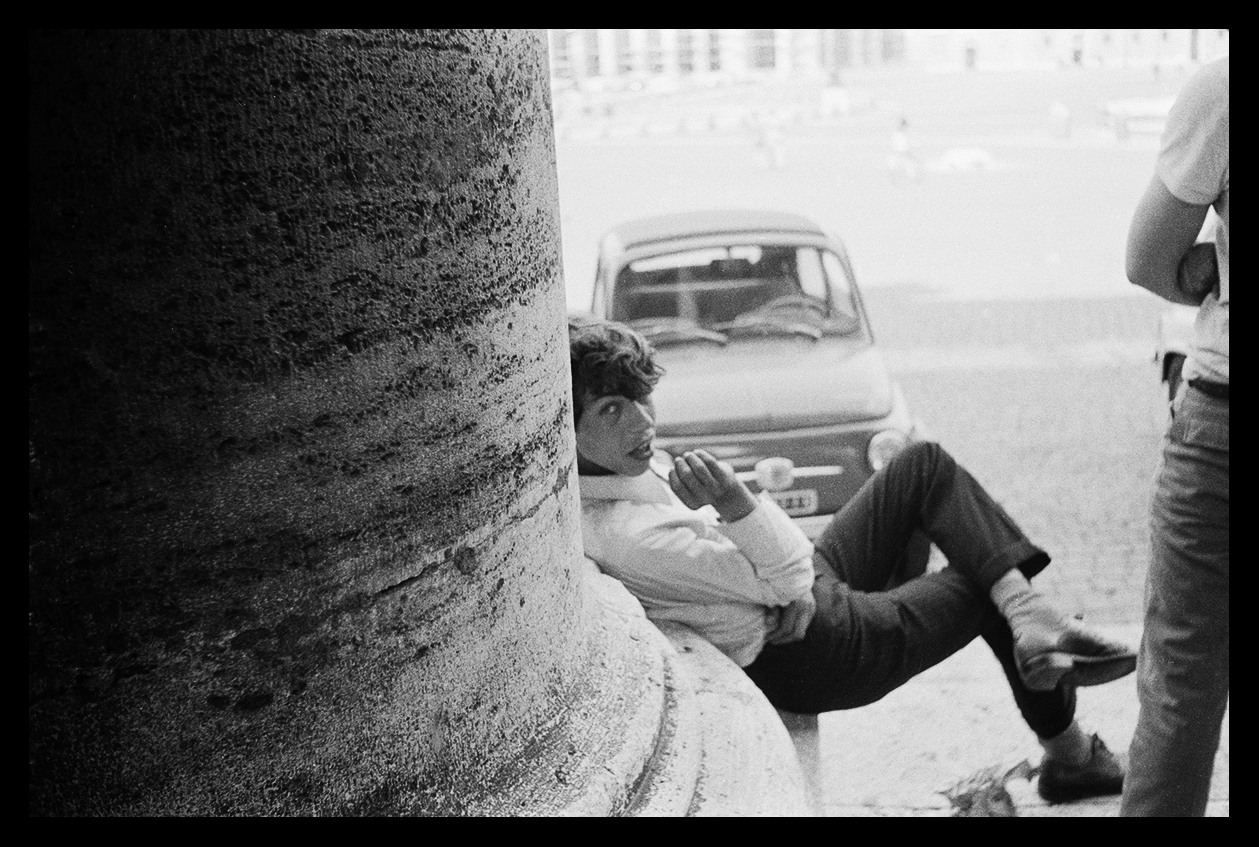

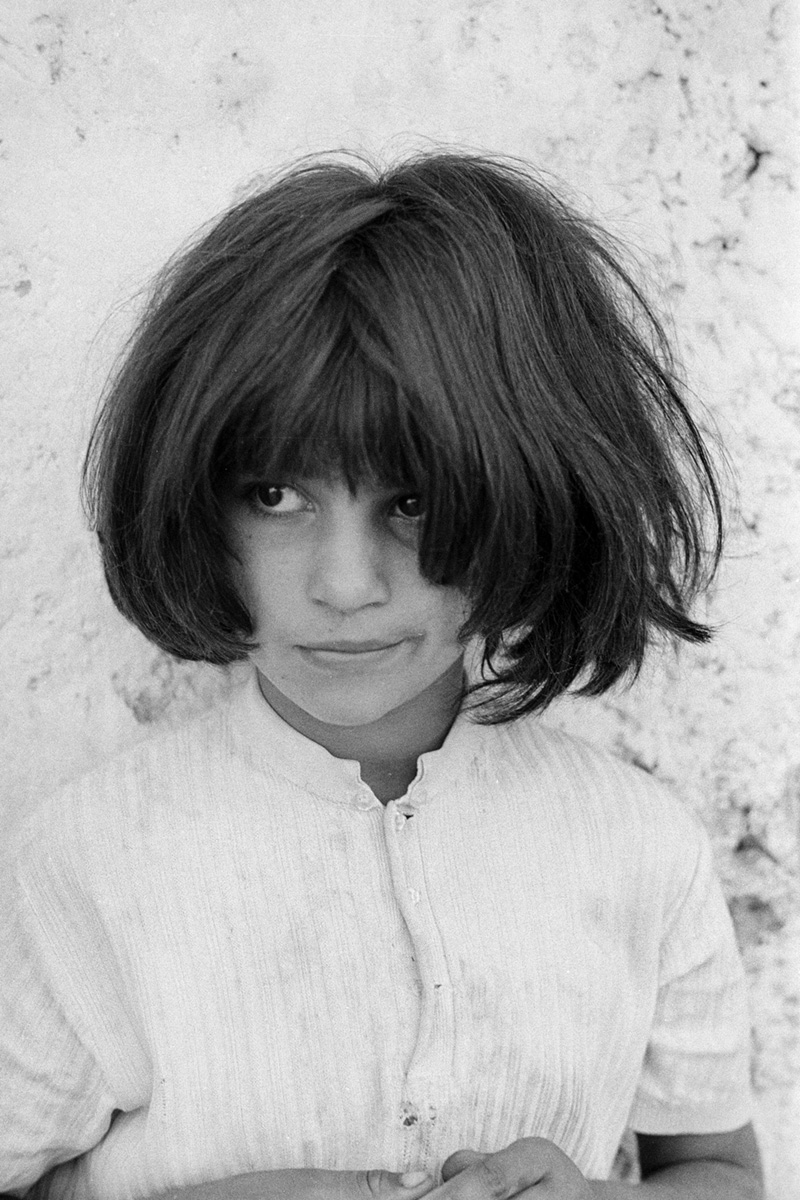

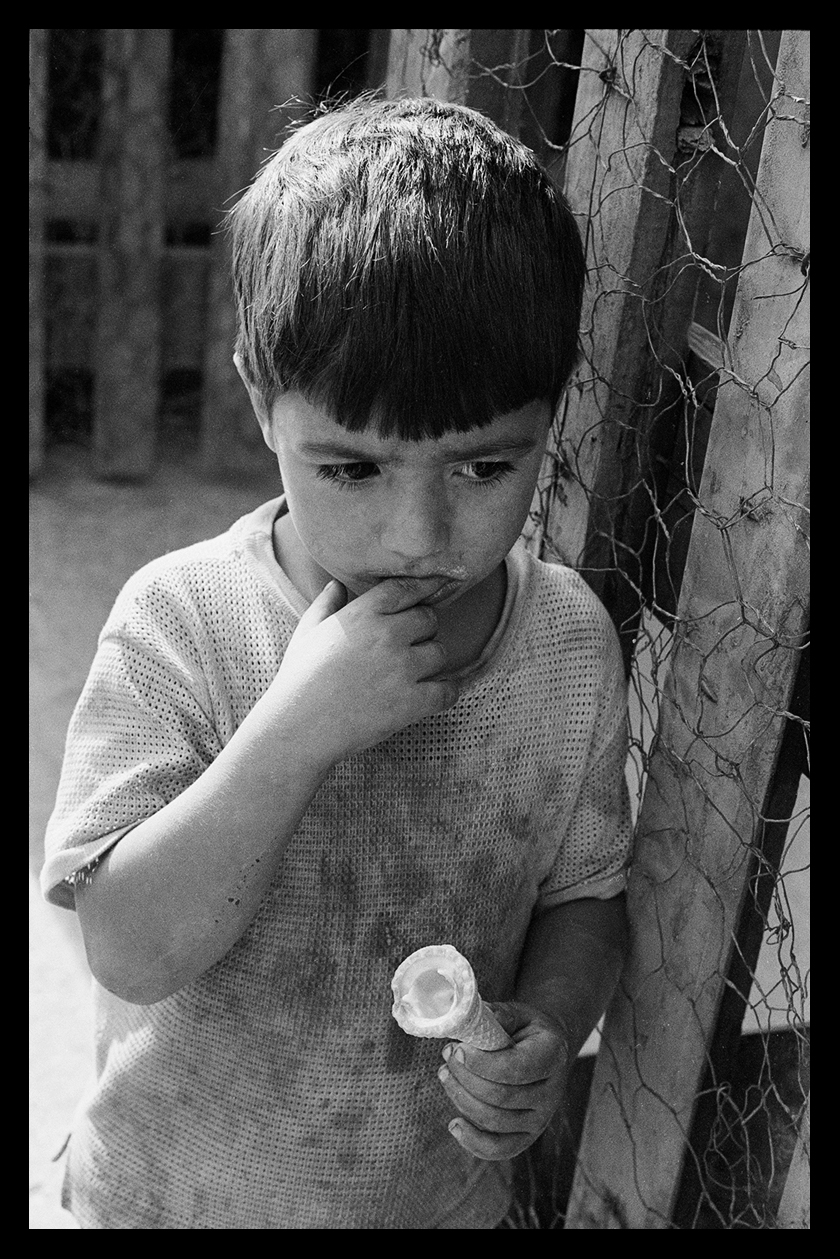

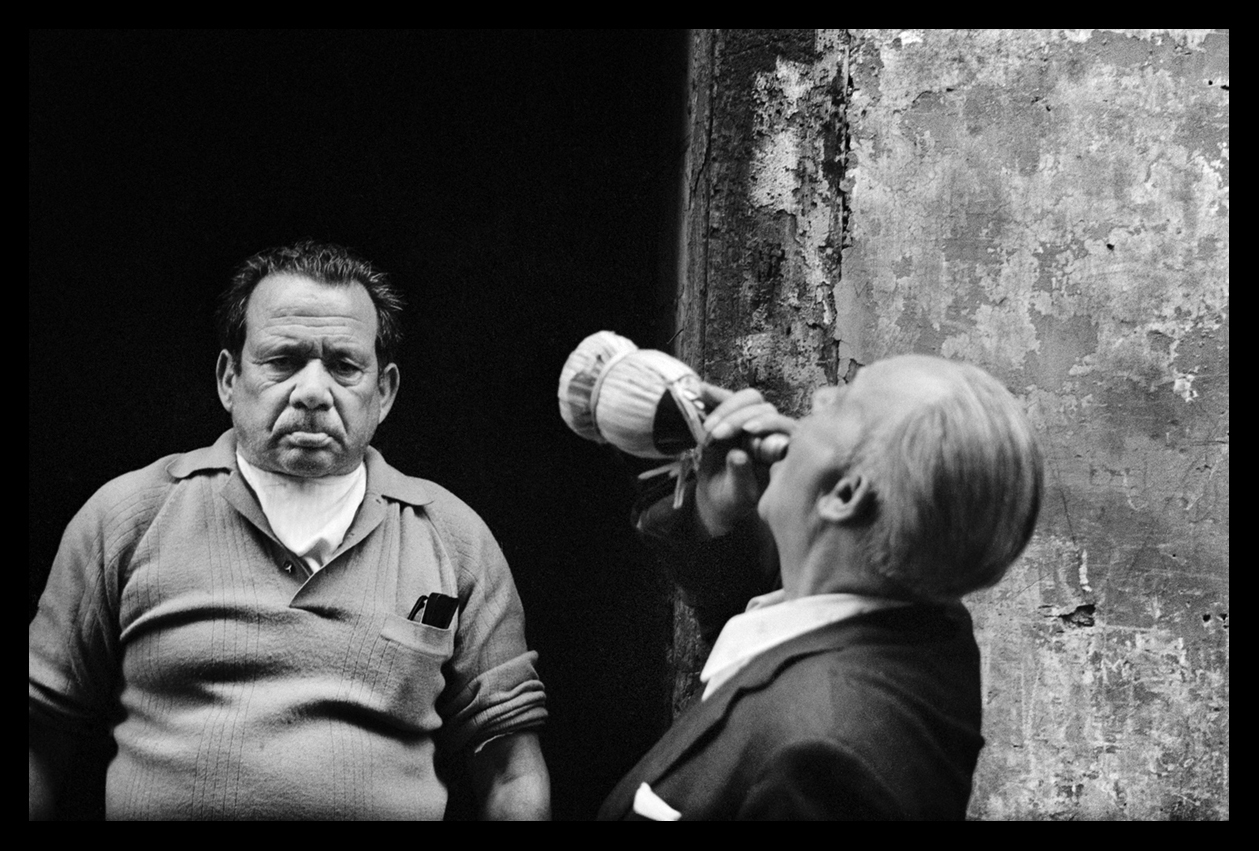

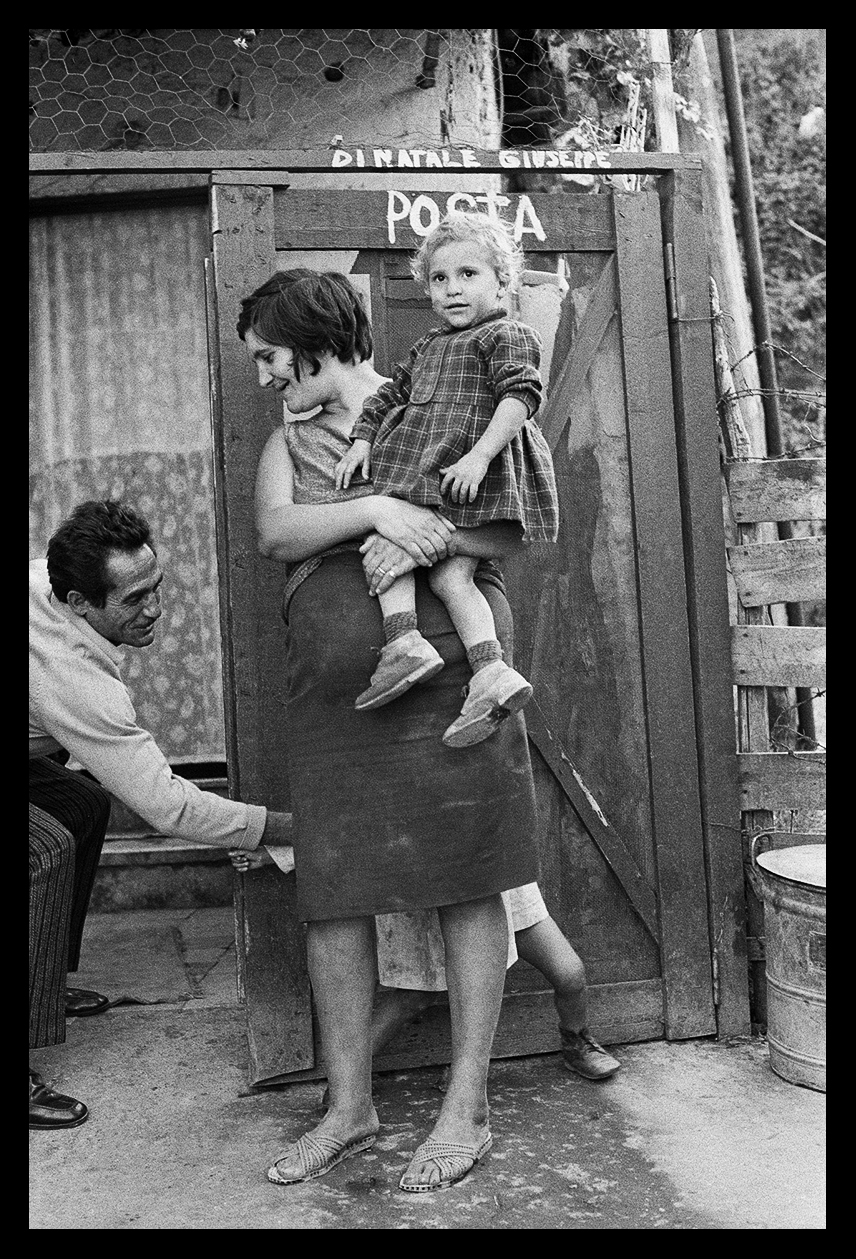

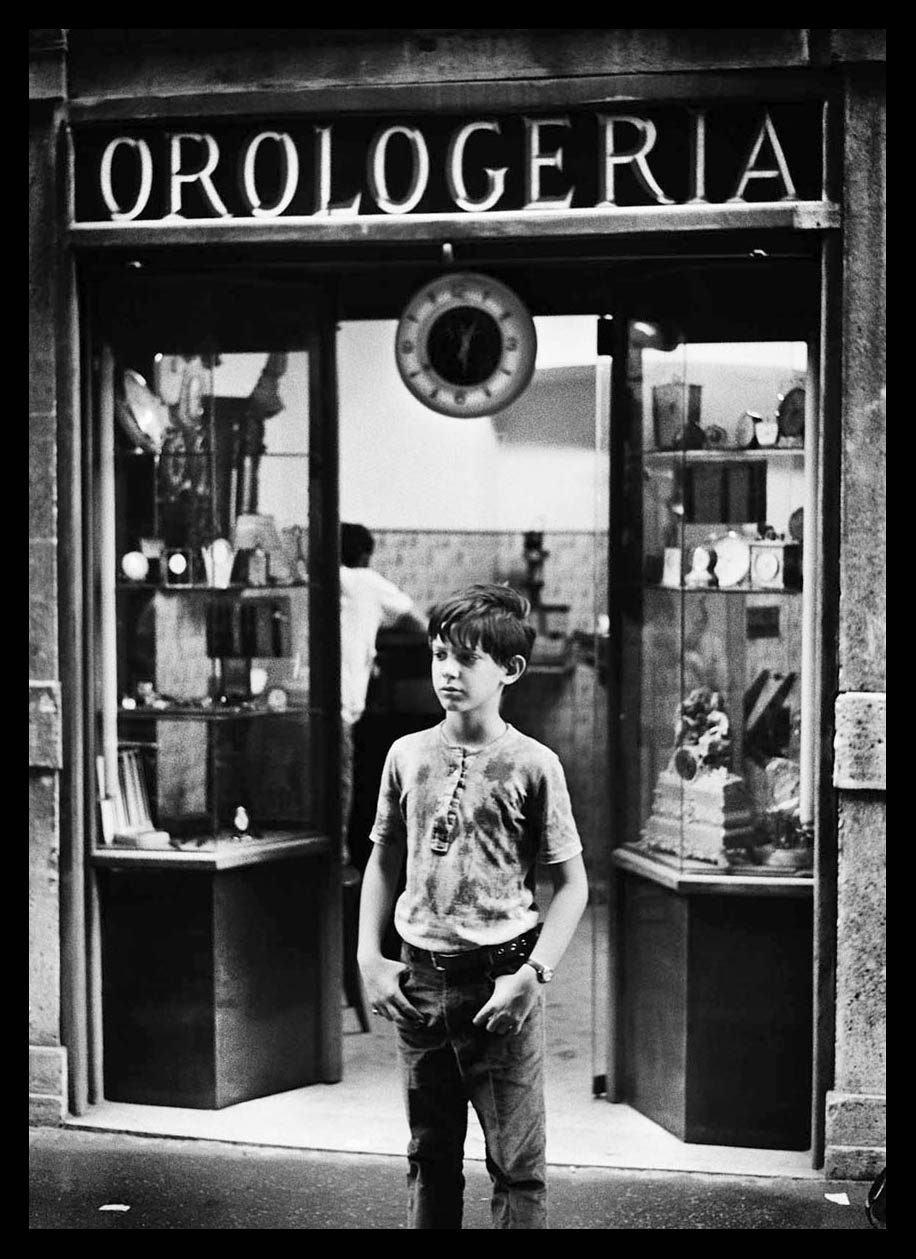

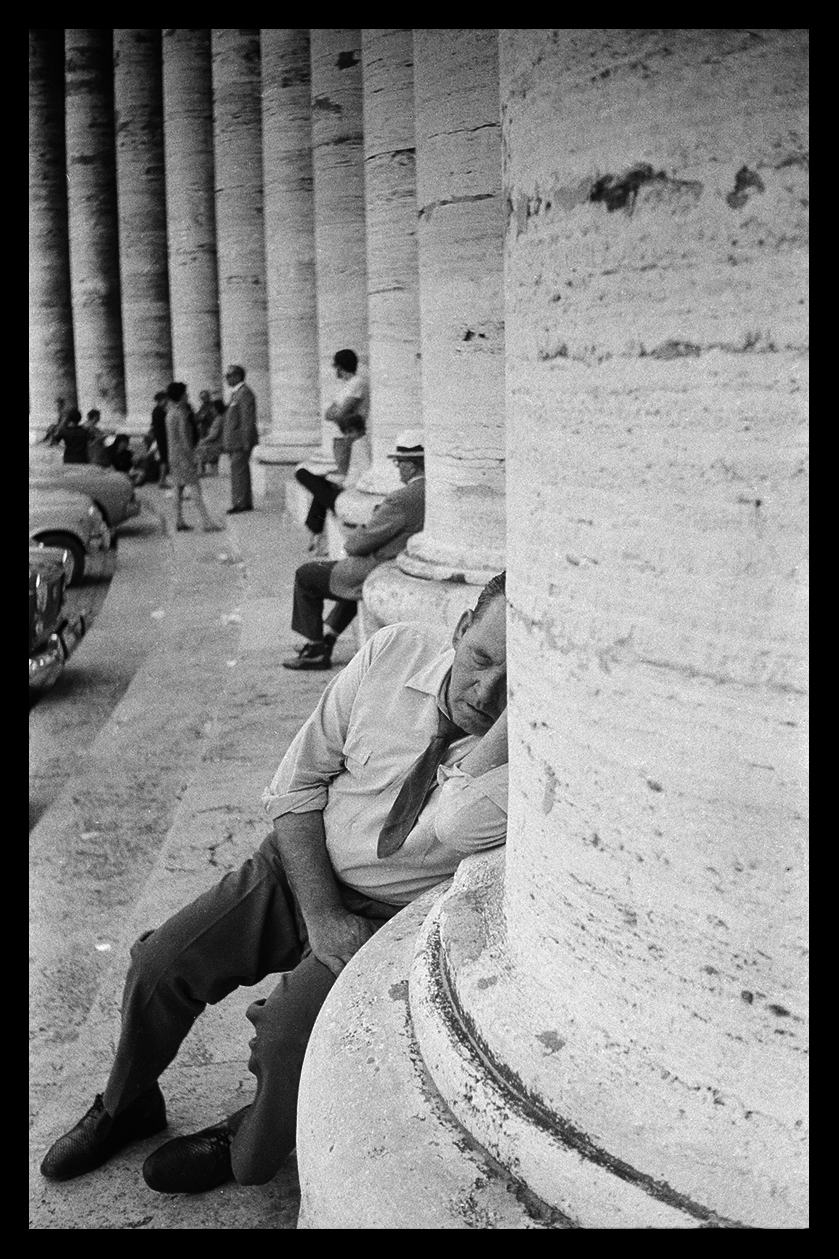

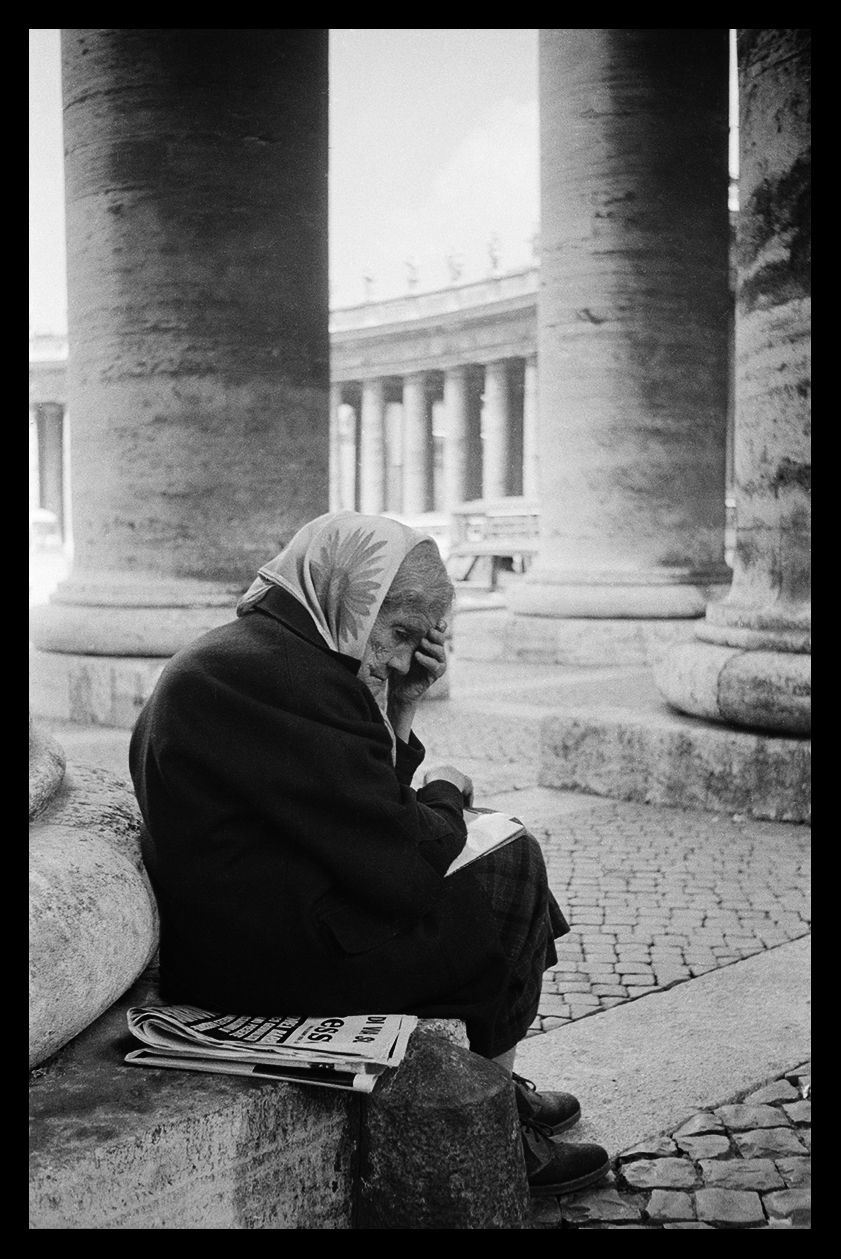

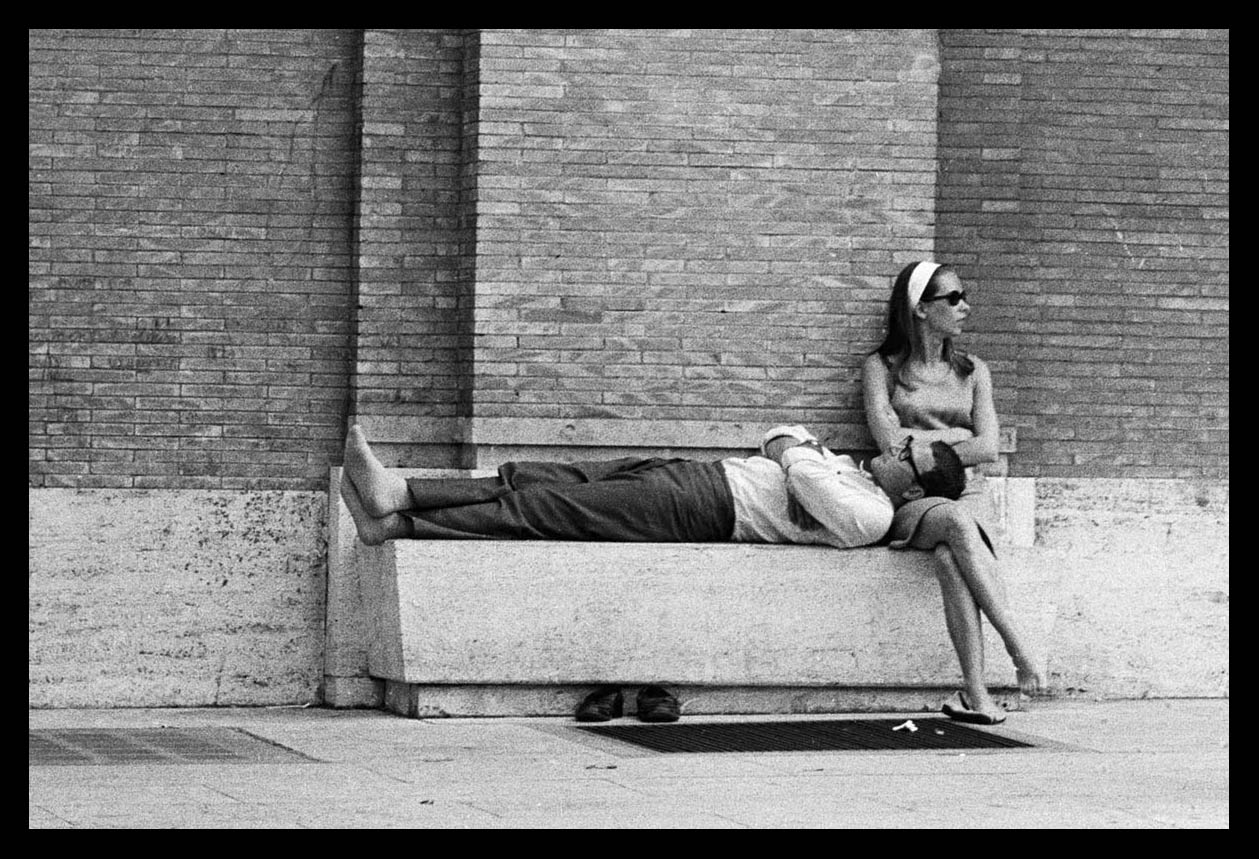

John Randolph Pepper (1958), is an American/Italian photographer. He was born and raised in Rome; lives in Palermo and works worldwide. Pepper started his career in Black & White analogical photography with an apprenticeship to Ugo Mulas at 14. He published his first photograph at 15 and had his first show at 17. He studied History of Art at Princeton University, where he was also the youngest member of the exclusive painting program, ‘185 Nassau Street’. He then became a ‘Directing Fellow’ at The American Film Institute, (Los Angeles) and subsequently worked as a director in theatre and film for 20 years. For thirty years, he dedicated himself to photography while directing both theatre and film. During that time he continued to take photographs with his Leica camera always using the same Ilford HP5 film stock. John R. Pepper, represented by the Art of Foto Gallery (St. Petersburg, Russia) and The Empty Quarter Gallery (Dubai, UAE), is a ‘Cultural Ambassador’ of numerous Italian Institutes of Culture in many parts of the world. Since 2008 he has exhibited his different projects ‘Rome: 1969 — An Homage to Italian Neo-Realist Cinema’, ‘Sans Papier’, ‘Evaporations’ in the United States, France, Italy, the Middle East and Russia. He has published three books and is represented in several major museums around the world.

– How and when did you become interested in photography?

For the record, I am an analogue photographer and only work with negative and even when developed I print through the negative, using the enlarger and not digitally. There is no post-production. What you see on the image is what is on the negative.

I grew up in Rome with a father who was the Bureau Chief of a magazine called Newsweek. It was a time when articles were accompanied by photographs therefore many photographers came through our family home as they would go on assignment with my father. From very little, 11 or 12 years old, I would listen to them speak about composition and pictures and color (Roloff Beny was always there and was very impressive) versus black and white (Capa, Cartier Bresson etc).

One can sort of say that I fell into it. When my father changed from his Pentax to a Nikon he gave me his old Pentax with a 50mm and 105mm. And when he would go on some assignment in the city, he would take me along. So, at 12 years old I had a camera around my neck and went with him and he taught me how to take photographs. I had my first photograph published in at 14. It was of Pope Paul VI.

I think the turning moment for me in photography, was when, as a child I was at the breakfast table at home. There was an old man (he seemed terribly old to me since I was so young) and he was talking with my father. He was explaining the ‘construction’ of a photograph (as well as all the colors that are in the shades of 0 to 9 — white to black). He talked with a French accent as he turned the photographs they were looking at upside down and analyzed the image in relation to is geometrical construction. He dissected the image and it took on another dimension. It was about balance, and lines, and curves and harmony. He also turned it back and discussed the how these same lines and curves and planes in space receded and came forward and how they created depth and highlighted the subject.

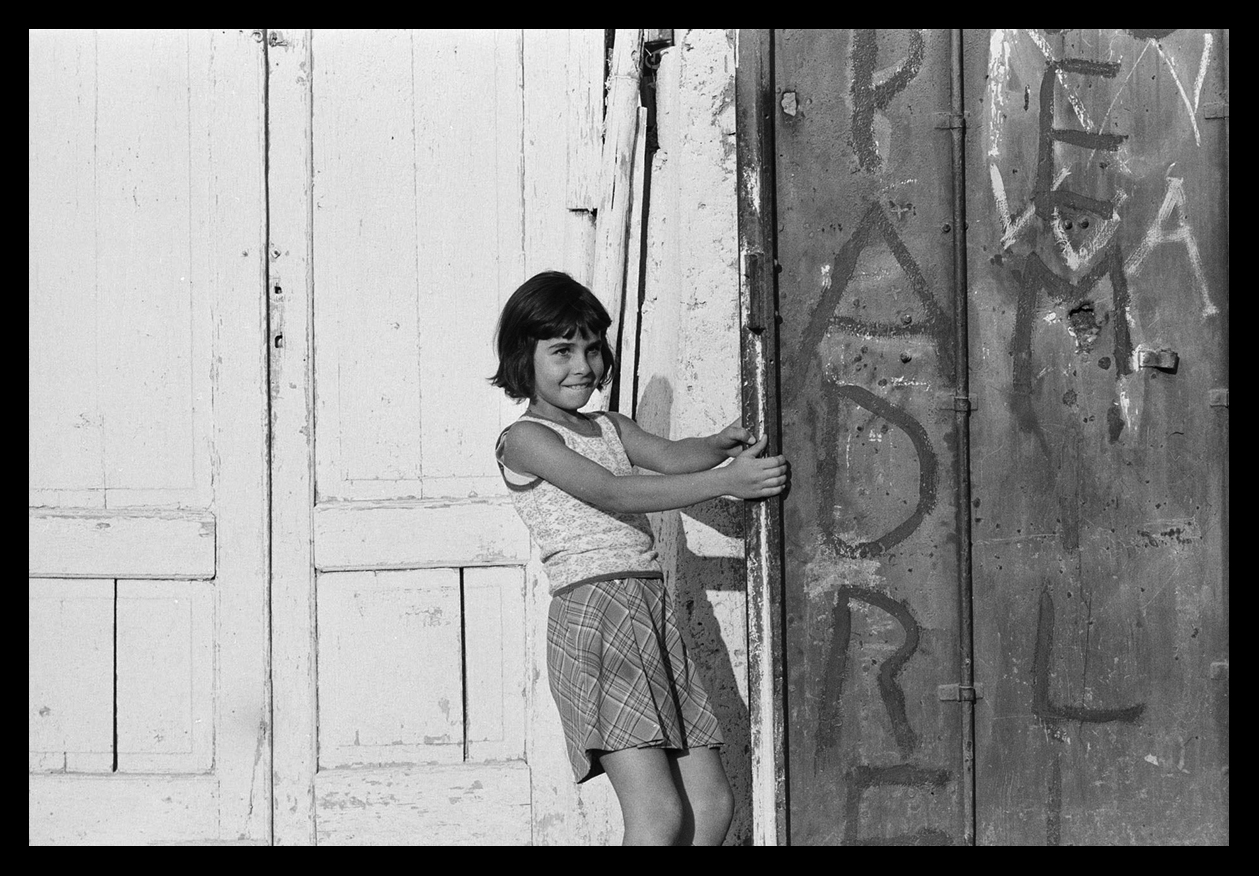

And then he also explained how one had ‘to invade the space of the subject’, without perturbing the subject, without aggressing the subject – how get ‘in and get out’, even before the subject realized what was happening and that a photograph had been taken.

He also stressed that every image also had to have a ‘story’; be it a face or a funeral or children playing, it always had to have a ‘narrative’.

It was a master class for my father and the source of everything for me. This old man was fascinating and inspiring and I felt there was something magical in all of this. Remember though that I was a child. So on the one had I ‘soaked it up’ and then on the other hand I did not think about it as an adult would. But it marked me. It stayed in my brain and I can remember the moment as if it was yesterday. I can actually see the whole scene and hear them talking.

The ‘old man’ was Henri Cartier Bresson.

But, of course, I had no idea who he was. He was just a kind, fascinating old man. It was only years later that I understood who he was.

– Is there any artist/photographer who inspired your art?

The world is divided into Beatles fans and Rolling Stones fans. I am a Beatles person.

In the photography equivalent I have always looked at, been inspired by:

Edward Weston,

Tina Modotti,

Ugo Mulas

Berenice Abbott,

Robert Frank,

Dorothea Lange,

Moholy-Nagy,

Cartier Bresson,

Steichen,

Steiglitz,

Paul Strand,

Minor White

Julia Margaret Cameron

Ralph Gibson

But if we have to single out a few specific ones, I would say: Bresson, Frank, Modotti and, of course, Ugo Mulas to whom I was apprenticed at 14.

They always were interested in the ‘Soul’ of their subjects (as were the others but these talked to me more). They captured the people in their individual settings and locations — and in doing this they gave us, the viewers, a sense of time and place and the pathos and drama.

The others, all GREATS, are more like Rolling Stones for me: I liked the music, but I never learned the songs by heart. What follows are some of the others whom I have looked at, appreciated and admired, but always kept a bit of space between myself and them:

NOTE: None of these are not in order of importance and, again, these are GREAT photographers.

Ansel Adams**

Diane Arbus,

Nick Knight,

André Kertész,

Man Ray

David LaChapelle,

Robert Mapplethorpe

Saul Leiter,

Doc Edgerton

**Ansel Adams however accidentally became the source and inspiration for my most recent INHABITED DESERT series that is being show elsewhere in the world currently. But that is another story.

– Why do you work in black and white rather than color?

I love color. At Princeton University I majored in the History of Art (and specialized in 15th century Italian Renaissance painting) and was also an original member of the painting group ‘185 Nassau Street’ and color was all I thought about. From the Italian Renaissance to the ‘Fauves’ in Paris in the early 20th century to the American ‘Color Field’ painters of 1960’s.

In addition I grew up in Rome, a city known for its amazing red, white and ochre colors at the end of the day… Color is enriching and soothing.

However, I feel that in photography, working in color is like answering the questions. There is nothing left to ‘fill in’.

In B/W the range from 0 to 9 has all the subtleties of color yet it requires the mind’s eye to subliminally fill in the answers. It is the associations of the mind and the eye that dictate what the colors it could be. I also believe B/W leaves more mystery to the image and it also helps suspend time and place.

If one looks at Steve McCurry’s images, they are beautiful but everything is answered – there is little mystery.

The famous photograph of the Afghan Girl is mostly about the color of her eyes and of her robe. There is intensity in her eyes, enhanced by the color, but in B/W the same image might be even more powerful since the eyes would be all you would look at. Now, as it is, we are drawn in by the colors and then see the eyes in a second stage.

Compare the McCurry’s ‘Afghan Girl’ to Dorothea Lange’s ‘Migrant Mother’ (1936) and my point becomes very clear. ‘Migrant Mother’ in color would lose its power and become nothing other than a nice picture for National Geographic Magazine.

– How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph/series of photographs?

In the question “How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph” there is already a caveat: it implies going out with a specific end goal — with the desire, the determination for a result. And in proceeding in such a manner one often finds oneself with many images taken but without a photograph that stands out and speaks to the viewer.

It is similar to when a person wakes up one morning and decides to fall in love. We all know that it never happens when one wants to fall in love. But the moment you give up on it, that you stop looking, then the odds are that you will walk through a door or onto a train or stand in line and suddenly you see/encounter a person and the sparks fly and your heart starts beating.

Unless you are working in a studio and doing a still life or something specific and the work is technical (note that it can also be artistic), it is hard to prepare and plan for the photograph. Technique is important but it is also a trap and a handicap. Of course Ansel Adam’s books on technique are fascinating and important to read and learn from but then, in the field one must forget about all that and relay on two important elements: your eye and emptying your mind.

Minor White wrote (1952):

“… Looking has its own quality. This means that you look through the eyes of a child, with honesty and recognition of a miracle; it also means to see through the eyes of an adult who has come full circle and once again sees as a child – fresh and with an even more profound sense of wonder. ”

White, Lange, Bresson, and I would wager all the great photographers, you admire or are interested in, will concur that one needs to empty one’s mind of all thoughts, of all ideas, of all concepts of everything and allow, give yourself permission to look at the world you’re in as though it were the first time you saw anything. Regardless if it is urban or rural, a poor neighborhood, a war zone or a pastoral setting you need to ‘see’ it with fresh, open eyes, with the innocence of a child and see what happens. You look at it, you drink it, eat it, smell it with your eyes and allow the image to come to you. For it is imperative that all of you, the whole mind and body, not just the frontal lobe but the rear lobe as well, are free of any thoughts or worries or concerns (of course there must be no interruptions by phones or anything exterior — you are in your own bubble). If you try this technique it is certain you will be surprised by the results.

One last note: Cartier Bresson kept the book Zen and the Art of Archery by Eugen Herrigel at his bedside. The current English language edition has a preface by the master of Zen, Shunryu Suzuki (“If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything, it is open to everything…”). I suggest anyone who wants to take a photograph, amateur or professional, read the book. It will be a revelation and underscore my thoughts.

The preparation for taking a photograph happens way before you go out to try to take the photograph.

As I mentioned above there are two factors: your eye and emptying your mind. I have gone over my thoughts on emptying the mind now let’s discuss the other, critical aspect of preparation: training one’s eye.

Without the ‘eye’ to ‘see’ one is just ‘looking’ and you will have a difficult time in seeing beyond what is in front of you. How does one do that? I call it going backwards before going forwards.

It is imperative to look at paintings from the earliest of times: from the Italian and Northern Renaissance, to Modern art to architecture etc. You need to read about them and understand the construction (remember I mentioned Cartier Bresson and ‘construction’ in the first question?) and see how light is used –such as in Caravaggio or in Vermeer or in Monet and Manet, to give a few examples. You need to look at Mark Rothko’s Color Field paintings and see how he uses light. The list is endless.

You need to train your eye in every possible manner. Surround yourself with books or search the Internet and gradually you will be able to discover that you are looking at the image differently because you know what is being attempted by the artist – or at least you believe you are understanding what they are going for.

Once you have done that and you have trained your eye, you must then forget it. You must not attempt to re-create it. You need to then apply the ‘empty mind’ set.

A trained eye and an empty mind are the foundations of my technique — and I believe many other Street Photographers as well. All you need is a subject (people, desert, water, cars…anything) and off you go, hunting. But remember that it necessary to not be judgmental, not to stand out and be dispassionate. For there if there is no empathy, no feeling, then your image might be spectacular but it will also be cold and detached and not grab the viewer’s emotion; it will not take their breath away.

I will end this question with a quote from Henri Cartier Bresson:

“The history of the image involves the joint functioning of the brain, eyes and heart. Sometimes a single event can be so saturated by itself … it is necessary to carefully go around it to find a solution that makes it … Sometimes you suddenly take a picture for a second, and sometimes it takes hours and days. But there is no standard plan, no model starting work. And your brain and eyes, and the heart must be observant; and your body needs the flexibility to respond … It is important to avoid the endless clicking of the shutter and the endless piles of documentation that are cluttering up memory and violates the accuracy of reporting in general. ”

– Where is your photography going? What projects would you like to accomplish?

In my most recent series, INHABITED DESERTS (one can see the images on my Instagram) I worked in deserts around the world. There are no people. None. I needed to get away from the label ‘Street Photographer’ and also remove myself from urban settings. I travelled 18,000km and worked in deserts around the world for almost three years.

That is done. And I, as an artist, don’t wish to repeat myself or stay in familiar territory. Some can do that. And they are satisfied and successful. I sometimes envy them. But it is not for me. I need to do something that is radically different.

So my next project will be to explore men and women again, in natural settings, naked.

You ask what I wish to accomplish: I want to — I need to — put myself creatively in ‘danger’ again. I aim to challenge myself to take photographs that place me, the artist, in an uncertain territory — where I don’t know what is going to happen, if I will succeed or not, and what or how I will actually photograph.

I have the subject and the locations and when I commence the work, I will apply all I discussed above.

Websites:

johnrpepper.it

www.rawstreetphotogallery.com