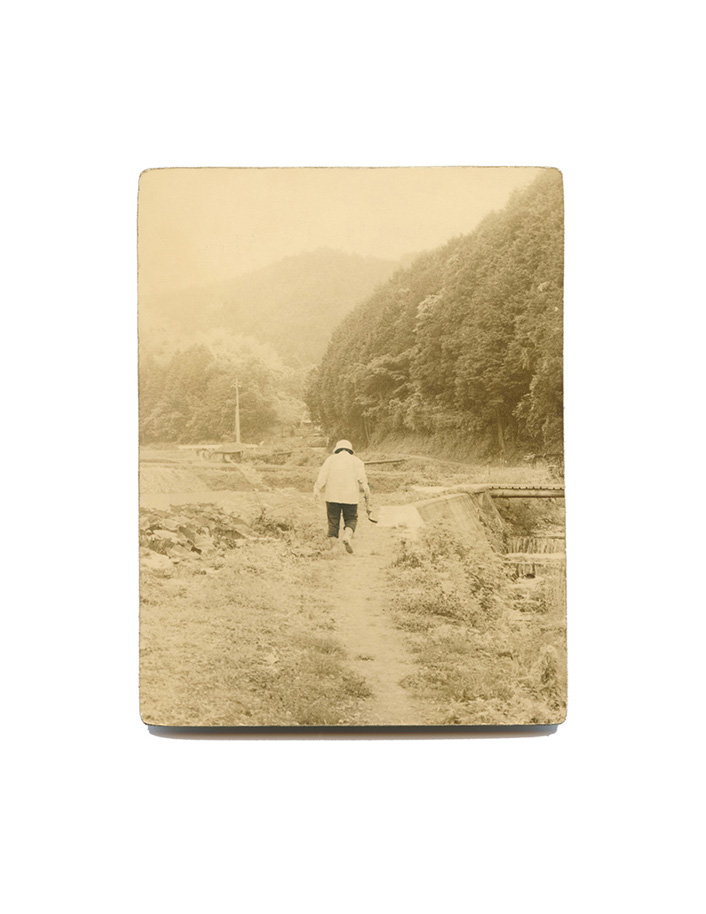

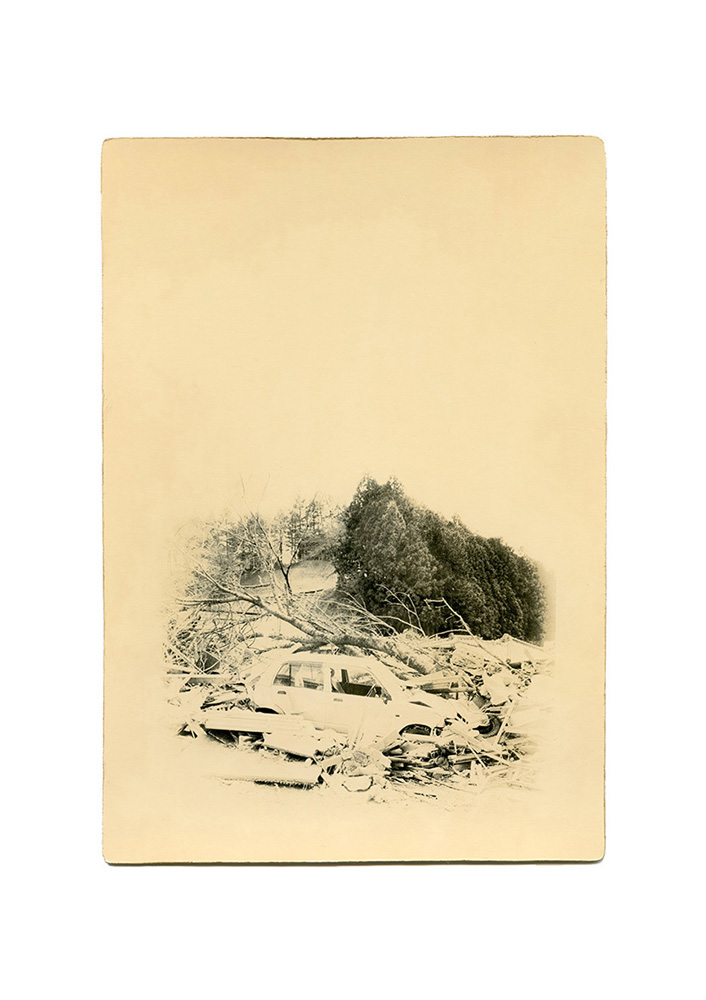

I was born in 1973 in Okayama, Japan, and at 18 moved to California, where I studied at the San Francisco Art Institute. I began there as a painting major, but little by little turned to photography. I finished by fine arts degree at Concordia University, Montreal, Canada. Upon graduation, I returned to Japan and became a journalist, producing TV news and documentary programs for foreign news outlets. After a year covering the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, I decided to go back to photography.

“I visited to Japan when I was a kid. It was wonderful!” A woman told me that in Boston one month after the accident. “Please come again” I was about to reply, but then I remembered about the Fukushima accident, so I didn’t. I remember the pain I felt on my throat. In my mind, the future image of Japan was totally deserted like a hell covered with dead plants.

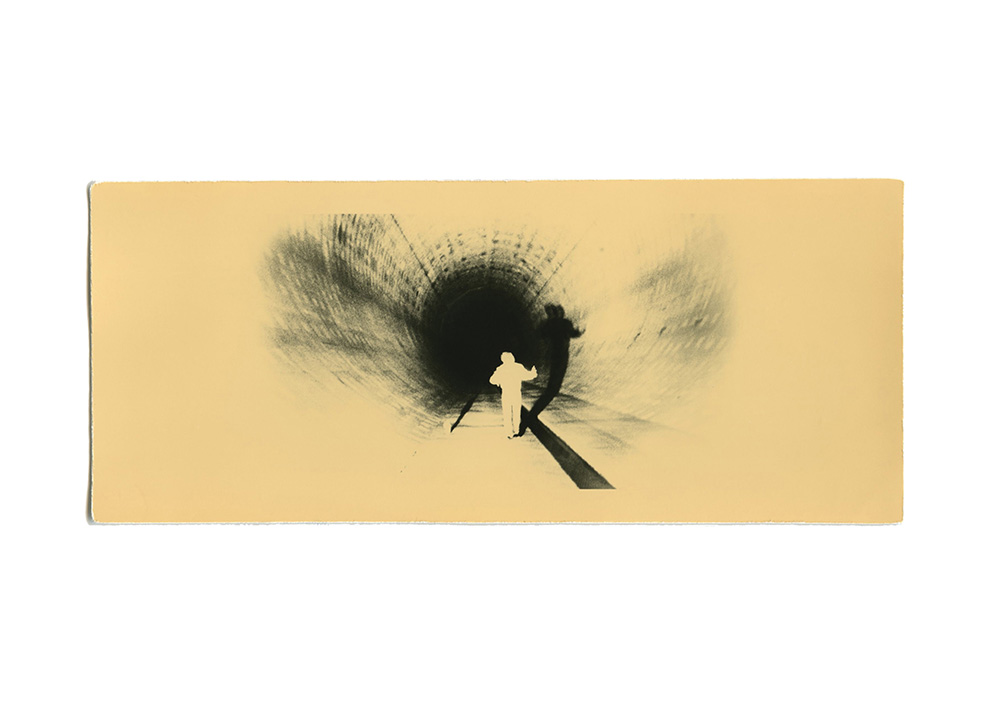

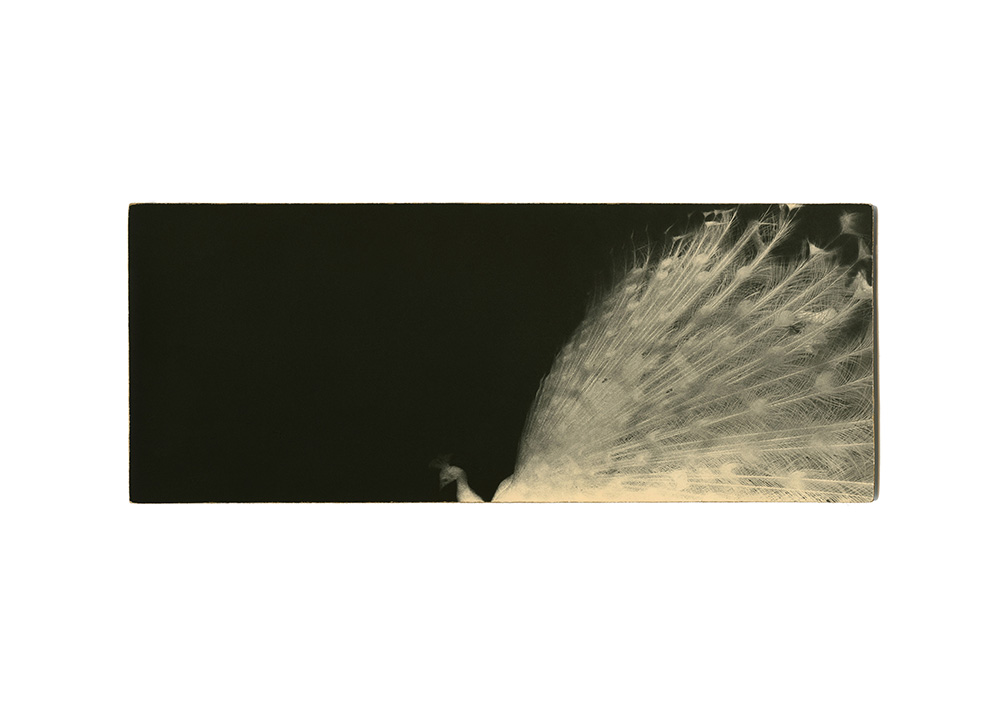

Right after the Fukushima nuclear plant accident, I found a blog about peacocks that were left in the evacuation zone, within the 20 km limit. I started imagining those peacocks, walking around the empty town with their beautiful wings spread. The image I had in my mind seemed so far away from what was going on in Fukushima. It was as if two different layers of images – the disaster scene and beautiful peacocks – were overlapping with each other without being unified.

I started to see different layers in almost everything after the disaster in 2011.

The Fukushima accident had a great impact on us, and yet, most of us don’t know exactly what happened, what is happening or what will happen in the future. We all have to choose the information that seems the most reliable and act accordingly. We don’t even know if Japan is safe or not. Some specialists say, “There is no problem” and others say “It’s seriously dangerous.”

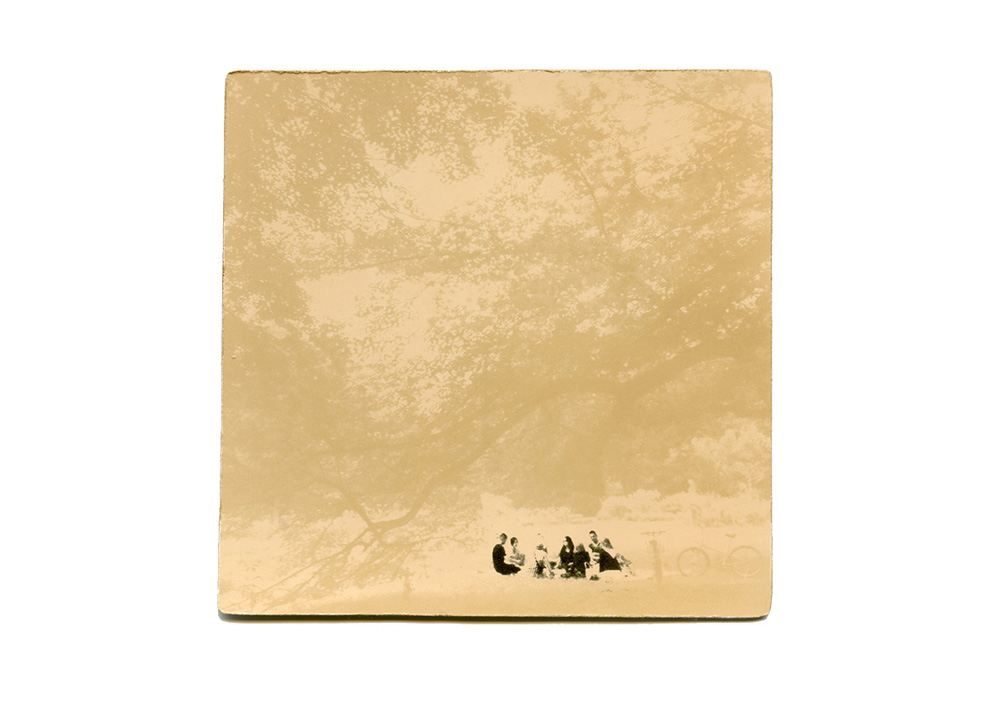

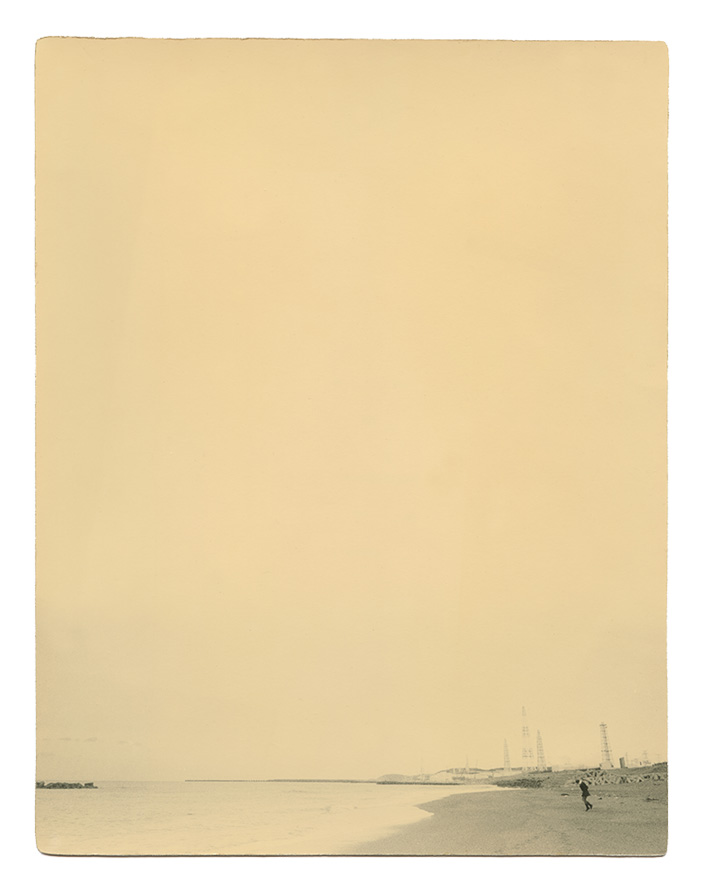

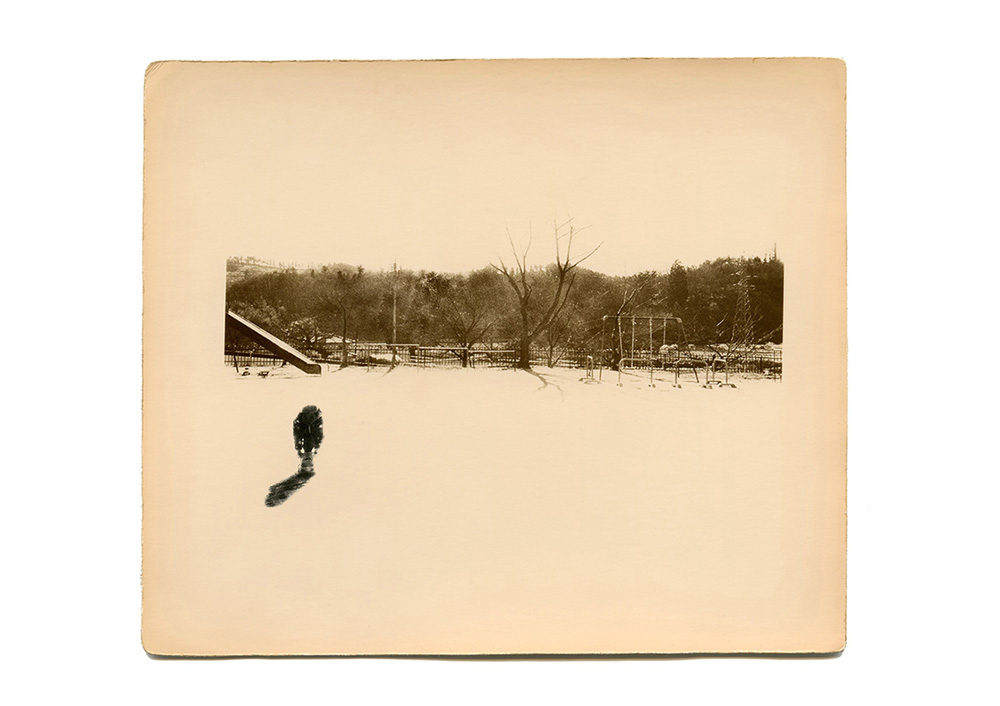

Tokyo was chosen as the host city for 2020 Olympic games. Some evacuees have started to return home and many farmers and fishermen have started to work again. Others have started to move away – towards the west – to be further from the Fukushima plants. Seasons come and go, people fall in love, kids play.

Many different layers overlap; the visible, the invisible, what we think we should see, what we know, what we feel with our five senses and sometimes our sixth. In this layered world, I started to feel pain and sorrow more vividly, but also beauty and happiness.

In my project ‘Layers,’ I use text to suggest other layers floating around my images, but it is not my intention to introduce a pessimistic note or romanticize tragedy. Probably the world has been always made of many different layers – even before the disaster. And there have been always problems, and beautiful things have always remained beautiful…

1. How and when did you become interested in photography?

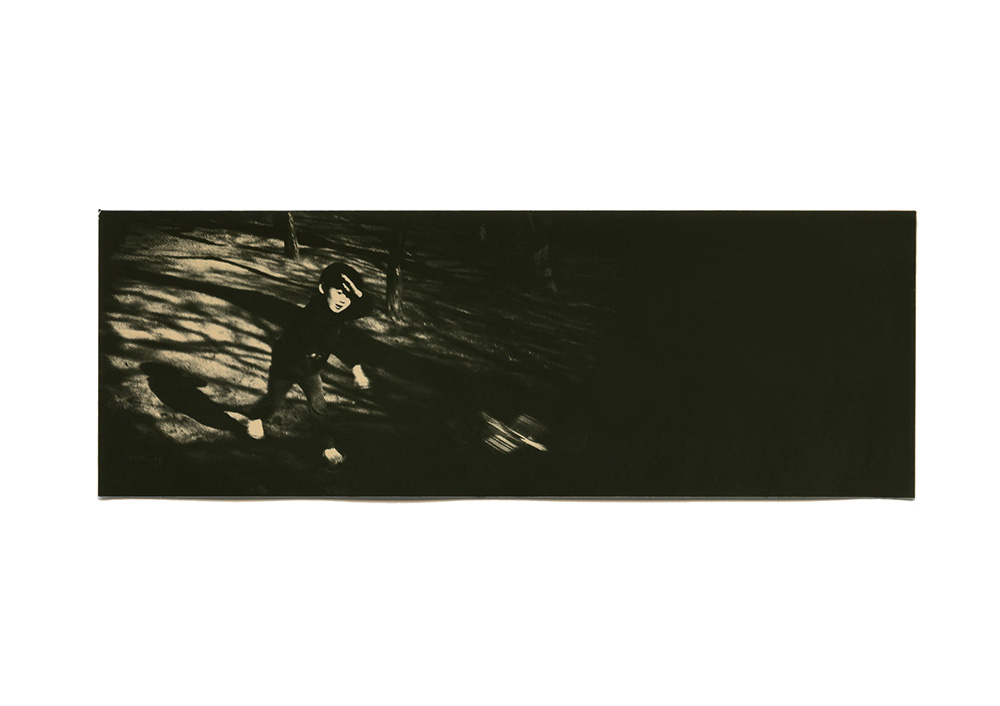

I was born and raised in Japan. When I was 18, I moved to San Francisco to study painting at the San Francisco Art Institute. I met photography there. My first photography teacher was Ansel Adams’s former assistant, but at the time, I didn’t know who he was or anything about photography. Despite this, I fell in love with the medium from the moment I put paper into the developer. I don’t know how many people have the same experience, but it’s like magic! I’ve been totally mesmerised by it since then. It’s also why I’m still working with gelatin silver prints. I am like a fossil, but I just love it.

2. Is there any artist/photographer who inspired your art?

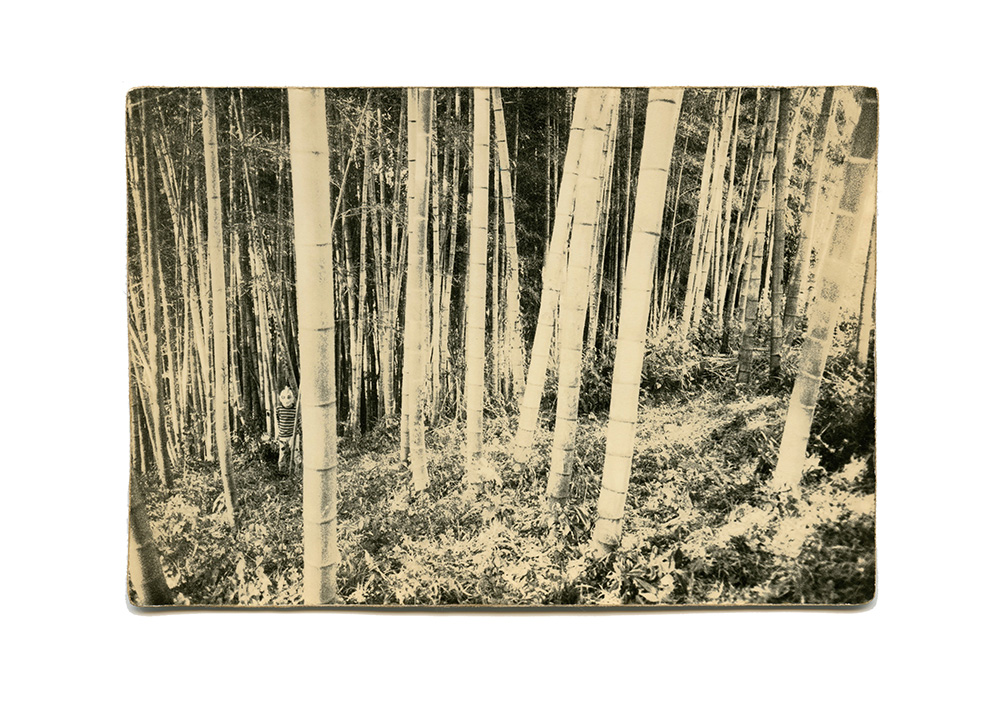

Of course there are artists I love and who’ve inspired me: Egon Schiele, Giacometti, Mark Rothko, Giorgio de Chirico, Marcel Duchamp and Edgar Degas, for instance. However, I think the biggest inspiration for my work is Japan, and Japanese aesthetics in particular. I remember in San Francisco I had a painting teacher who dressed like a cowboy. He said to me: “You have unfinished spaces. Fill them with paint!” I replied: “There’s no need. This is complete.” This was the first time I realised I unconsciously had a natural sense for Japanese aesthetics, which praises the beauty of emptiness. I love Hokusai and Sengai (a Zen Buddhist monk).

Many people comment that my work looks like that of Masao Yamamoto. Of course he is a great inspiration and I love his work. He is also a close friend of mine, and is my master as well in many ways. We’ve known each other for more than 15 years. He often tells me: “You will get a lot of comments and criticism saying that your work seems like mine. But that is just a style and your work is very different to mine. People who really can see the heart of your work already know that.” For him, style is just a style and it can never be the central part of a person’s art. He reminds me not to listen to those who are only interested in style, and to keep pursuing what I believe to be right. Then slowly but surely I know I will find my own distinct style so people won’t think about his work anymore. Yamamoto told me that the only way to reach this point is by producing work, not by planning or using my head. “So keep working!”

He also says: “Your work remind people of mine, because almost no one has this kind of style except us. Many people do large colour prints but nobody says they look like Tillman’s work. People love to compare work with something familiar, but don’t listen to them. Because those only see the surface.”

Even before I met him, my work was mainly small black and white prints so I believe this is also my style. I appreciate and try to pursue the beauty of emptiness and wabi-sabi; rustic elegance, quiet taste, refined beauty and the belief that objects gain value through use and age. What people call ‘Yamamoto style’, to me, can also be called ‘Japanese style’, which is very different from Araki or Moriyama’s work.

Not only this, but I believe that the biggest reason my work reminds people of Yamamoto’s is that it’s not as strong or attractive enough yet. I haven’t reached the point that my photography can grab people’s hearts without letting them be distracted by style or anything else. I’m constantly working on this.

3. Why do you work in black and white rather than colour?

Simply because colour images don’t excite me as much as black and white ones do.

4. How much preparation do you put into taking a photograph/series of photographs?

For me, taking pictures is just a preparation process. It is rather like collecting materials. I take pictures with film, develop them, make contact sheets, and then the fun part starts. Darkroom work is my favourite part of the process. I try to manipulate the image by playing with contrast, exposure, size and composition. I do dogging a lot and sometimes, I feel like dancing in front of the enlarger. Then after printing, I start toning with chemicals, and then I trim them and finish the edges. Even though my prints are small, it takes a lot of time to complete a single image.

5. Where is your photography going? What projects would you like to accomplish?

I have a lot of ideas for future projects. Since I still paint and draw, and also work as a journalist, I would like to combine those elements with my photography. I only returned to art two years ago, so I want to play with its many possibilities and try to find out which direction I want to go.

Website: mihokajioka.com

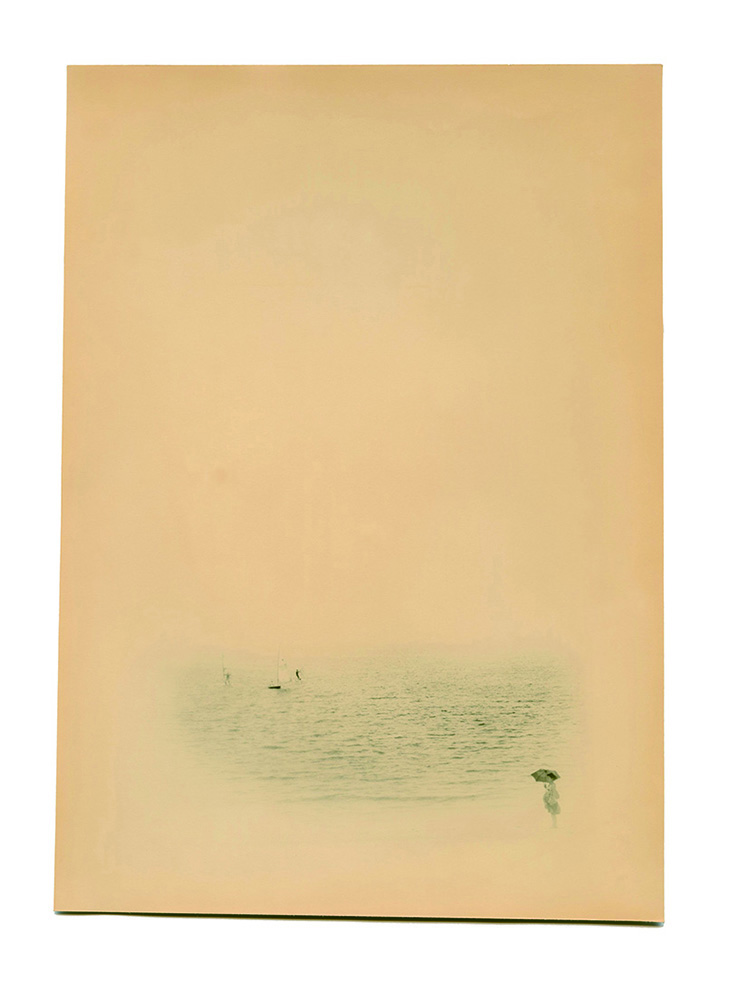

A big belly, my friend had. Hadn’t seen her for a long time. It was a beautiful afternoon on Hayama beach, 270.6km away from the Fukushima plant and it was the second summer from the accident.

I thought people living close to nuclear plants were all against to restarting plants, after seeing what happened in Fukushima.

“Welcome to Japan, a country of earthquakes!” A relatively big earthquake happened while we were shooting. To comfort a Brazilian co-worker who just had moved to Japan, I said that. It was two days before the real big one.

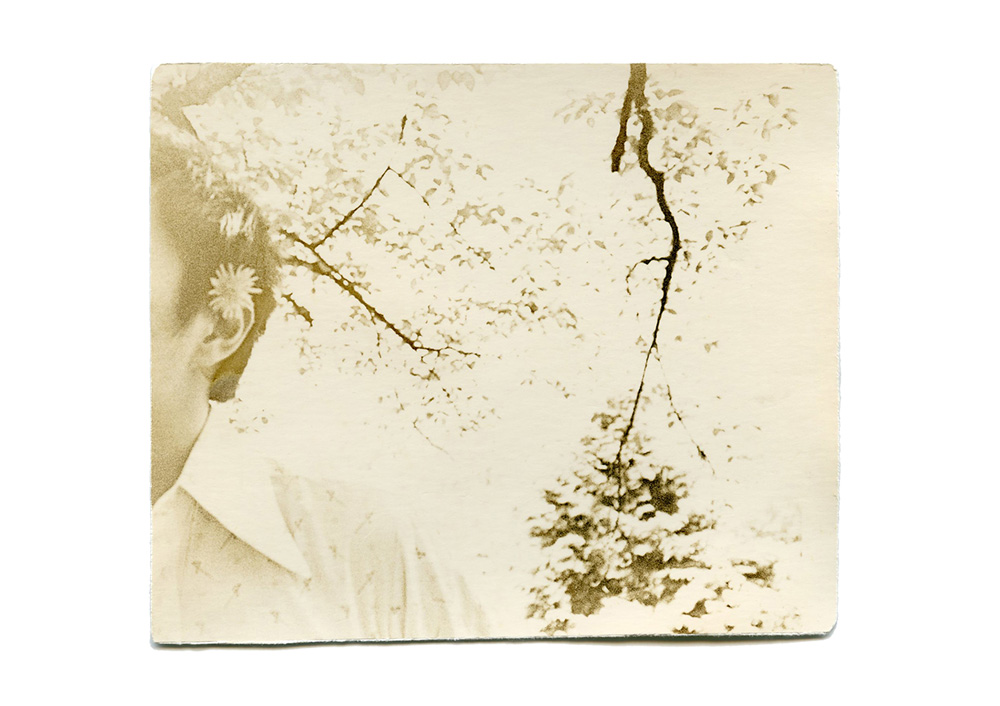

I found pink roses blooming beside a blasted building, so innocently. They had no sense to behave appropriately considering the situation and bloomed simply because the weather became warmer. I was so moved…

My grandmother, who was diagnosed with dementia, started to lose her memory four years ago. She doesn’t know anything about the earthquake, tsunami, Fukushima accident or anything. Everyday, she is just quietly smiling.

Right after the Fukushima nuclear plant accident, I found a blog about peacocks that were left in the evacuation zone, within the 20 km limit. I started imagining those peacocks, walking around the empty town with their beautiful wings spread.

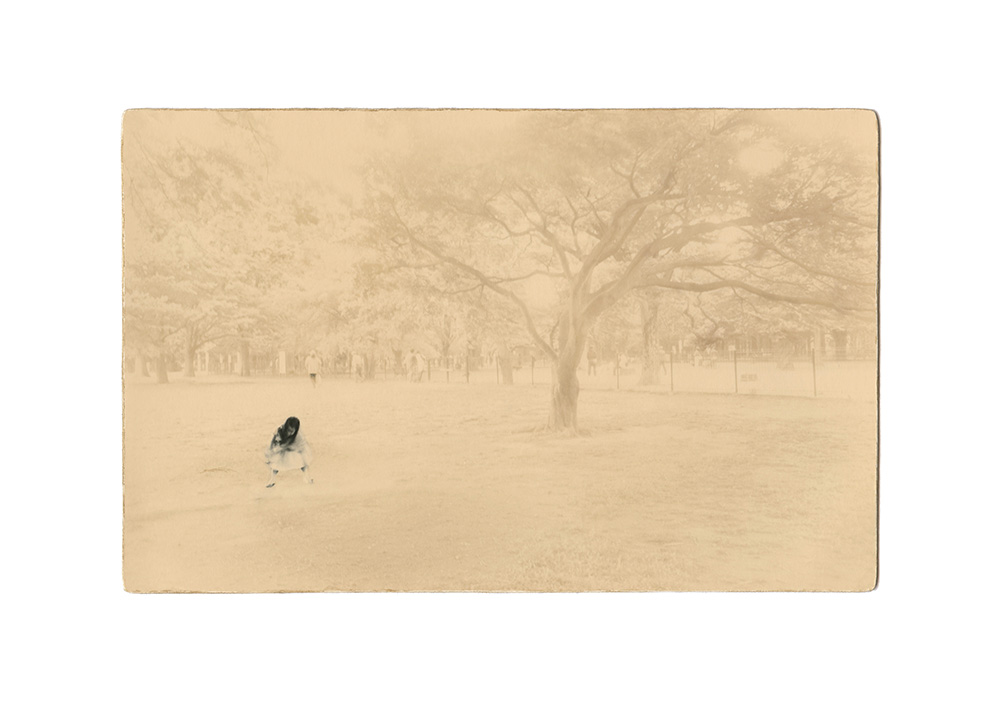

“Many of our friends moved away from here so I am a bit sad.” Said a boy who was playing at a playground of a kindergarten, where is 65 km away from the Fukushima plant. Right next to them, there was a temporary storage space for bags contained contaminated soils.

In Tohoku, the northern part of Japan where the tsunami hit, all kinds of flowers bloom at the same time in the spring. In an empty village, I saw cherry blossoms, peach flowers, mimosas and magnolias all together. It looked like heaven and it was my first Tohoku spring.

A research group caught butterflies in Fukushima and found out 12 % of them had abnormalities and the rate of the 2nd generation is much higher — even worse in the 3rd generation.

“Thank you very much for coming here. Please take care of yourself,” almost everyone said that to us, who were interviewing disaster victims, not knowing if that was really right things to do…

“We chose the way to walk ahead! The energy will come to us if we try!” This is from a letter written by a six years-old kid to his mother. They evacuated to Okinawa island.

Born and raised in a country that is stable and rich with no wars, I was working to report news such as terror attacks, wars, disasters etc. And one day, the disaster that happened in my country became the top news of the world. Then, Gaddafi took over the top place. So it goes.

“This is my third time that tsunami washed away my houses!” said a man in his 80’s with a big laugh. “Not a big deal. I will just rebuild another one.”

“Hopefully the situation would be better by the cherry blossom season.” Many disaster victims said that to us. When the season came in Tokyo, I drank a beer under cherry trees and thought about them.